Tutors and Dormitory Life

Many aspects of dormitory life are covered in other parts of the website – fagging and ‘brew-ups’, bathrooms and ‘tishes.’ This section looks more at the interpersonal relationships which shaped the dormitory or house experience – interaction with peers, domestic staff, and the importance of the House or Dormitory Tutor, along with the traditional dormitory games.

The holding houses

Many students began their Wellington experience with one or more terms in a ‘holding house’ such as Upcott or Douro, while they waited for a space to become available in their allotted Dormitory.

For most, this allowed a gentler introduction to College life, which they found welcome:

‘With the other “new men”, I went for my first term to Upcott House which gave us a slightly more gentle introduction to College life. Our Tutor was Mr Leakey, a kind and gentle man ideally suited for the job. We had one Prefect from the main college, a senior boy of 17 who, as he looked just like a master, we automatically called “Sir” until we were told that it was surnames only between boys.’ Anonymous

‘For my first 2-3 terms I was in Douro, a “starters” house for Beresford and Orange Dormitories. The Tutor there was Mr Strachan, a physics teacher, who was a really lovely man.’ Christopher Birt (Beresford 1955-60)

In retrospect, some identified other benefits too:

‘”New men” were able to find their feet among boys of their own age. Boys destined for one of the other four Houses which stood outside College went straight to them on arrival. They were therefore immediately thrown, often on their own, into the College’s strictly hierarchical and largely unsympathetic and inward-looking society. We Dormitory boys, temporarily held in Upcott, made many lasting friendships with boys destined for other dormitories, so we had a raft of supportive contemporaries across College who we would meet in classrooms and on sports fields over the years.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

‘During my time, boys were forbidden to enter any other Dormitory or House without good reason. This rule severely restricted a boy’s social contact to those in his own Dormitory or House. One could not mix at meals either. Residence in a holding house provided a boy with companionship from his contemporaries within the other Dormitories whose new boys were lodged there.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

Although there were disadvantages:

‘For my first term or two I was housed in the Upcott, from which we had to trudge every day to the main College buildings. I found this irksome and was pleased to be able to get into the main Dormitory.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘I started at Heathcote and remember trudging the half a mile or so to College through the snow of one of the coldest winters on record.’

Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55)

‘I can certainly recall having to make the journey, along Back Drive and then cutting through the wood at the edge of New Ground, in snow on many occasions and regularly in rain. This would result in boys arriving at the start of a working day in a condition that was anything from damp to drenched! There being no change of clothing available, one just steamed gently through breakfast and completed the procedure when sandwiched like sardines into the overcrowded chapel!’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

Richard also recalled the specifics arrangements for the holding houses: ‘Upcott boys had a Day Room in College as they spent the whole day there. Boys in Douro, located next door along the Sandhurst Road, went back to it for lunch, hence they had no in-College room. The Upcott Day Room was situated at the point where the long colonnade from the Combermere Quads met the junction with Front Quad, near the Queen Victoria foundation stone.’

Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59) recounted a specific aspect of Upcott: ‘The Tutor, Mr Leakey, was famous for his little sex talk, a requirement for all new boys. In groups of four, we sat in his drawing room and tried not to giggle as he began his tried-and-true monologue which had the same opening we had all been told about in advance: “Now you know that part of the body known as the balls…”’

Dormitory atmosphere, initiation and bullying

Once in their main Dormitory or House, ‘new men’ were subjected to its customs and prevailing attitudes, whether good or bad.

Initiation ceremonies do not seem to have been common in this period, although a couple of respondents mentioned them:

‘Living conditions were reasonably comfortable once all the initiation ceremonies for “squealers” passed (e.g. being squashed by the main doors).’ Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52)

‘There was a good team spirit in the House which I enjoyed after I survived the rigours of my initiation as a new boy – singing Molly Malone on the mantelpiece in the common room while being pelted with cushions by the Prefects.’ Adrian Stephenson (Talbot 1957-61)

The reception from boys immediately senior to the newcomers could be more brutal:

‘I do remember that the boys who had come one or two terms earlier took great exception if we were at all familiar in the way we addressed them!’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘We were fairly set upon by the boys from the term before us, a practice that I hesitate to say we continued with our successors of the next term.’ Robert Hirst (Picton 1955-59)

Our respondents were not specifically asked to comment on bullying and most did not. Some were explicit about its absence:

‘There was no bullying in the Hardinge, although we were not so sure about the dormitories in the main block, which we considered a bit rough!’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘There was a great sense of pride in the Dormitory and, with the mix of ages, care for the younger boys (“squealers”).’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

But others described an uncomfortable atmosphere or, at times, particularly unpleasant incidents or individuals:

‘In the Combermere in your first term or so, some had to sleep in a dormitory and share during the day with the owner of a “tish”. Not a pleasant experience for me as he was rather a bully.’ Nick Harding (Combermere 1951-1955)

‘There was quite a lot of bullying of which the Tutor seemed unaware.’ Michael Trevor-Barnston (Anglesey 1957-60)

‘As to bullying, there was, disgracefully, some, mainly where there were weak Tutors and Prefects.’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘Often, during evenings, I hid away to avoid some bullying escapades in the Dormitory perpetuated by irresponsible and often dominant senior boys.’ Michael Crumplin (Orange 1956-60)

‘Life in the 1950s was, to me, mostly a matter of survival. A couple of boys from the year above me made life insufferable from time to time but in those days, bullying was part of school life…’ Ross Mallock (Murray 1954-59)

‘There was some nasty bullying, not, I think, by senior boys of their juniors, but by groups of boys who picked on selected victims for very unpleasant humiliations.’ Peter Marshall (Stanley 1947-51)

Dormitory games

Moving on to happier subjects, generations of Wellingtonians will remember some particular and traditional Dormitory games.

Although these might sound rough to modern ears, most of our respondents seem to have enjoyed them:

‘Under my oval window was an upholstered window-seat with a hard-stuffed, apparently indestructible headrest. Agonising when used as a pillow, it proved entirely suitable as the ball for many of our Dormitory games.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

‘The table for “swipes” was only removed when we played “fug rugby.” There were few rules. It was played with one of the triangular-ended cushions from our window seats, the aim being to wrestle it down to the opponents’ end of the corridor.’ Richard Craven (Hill 1950-54)

‘“Fug rugger” was fairly physical, but not over painful, unless one was hurled against one of the many protruding doorknobs.’

John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘We grew up in a robust physical world in which the main indoor recreation was “fug rugger”, a game played up and down the Dormitory passage, in which there were no rules and no limit to the number of participants. When not engaged in fug rugger, we tested our nerve by swinging precariously on a primitive trapeze erected at the far end of the Dormitory passage. I can’t imagine why nobody was seriously injured.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘Membership of the First XV was all. In my first few days I was amazed that these god-like figures would actually join us squits on a Saturday evening to play “fug rugger”.’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘I also used to enjoy fug rugger, fug hockey and fug cricket that were all played in the corridor between the two rows of “tishes.” Batting in the poor light was quite a challenge.’ Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953-57)

Those in the Picton had their own speciality, played in the underground tunnel which connected the Picton to the main College:

‘We used to play “tunnel hockey” along its length – that proved interesting, as the ball whipped off the tiled concrete surface at high speed, deflected by the bend halfway down which was the point at which it first became visible. It was rather like blind racquets with a much larger ball. I recall being struck on the bridge of my nose on the last day of term, breaking it and causing a massive bruise in the middle of a tightly swollen face. To make it even more interesting, we sometimes used flaming balls of newspaper instead.’ Anonymous

‘This game was played with ideally three players on each side, an ancient ice hockey puck which was kept in the Picton common room, and some old hockey sticks. It was quick, rough and exhausting. There was a lot of running and body checking and bouncing off the walls, and it was huge fun. A few bumps and bruises were easily put right by a hot shower afterwards. Interestingly, there were hardly any real injuries, due to the narrowness of the tunnel, which limited the amount of kinetic energy a body could generate. Teams could be drawn from the Picton or against other houses or dormitories. I do not believe the existence of tunnel hockey was known to the staff.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

House and Dormitory Tutors

Each House or Dormitory was under the charge of a Tutor, or Housemaster as he would now be called. Although day-to-day organisation and discipline were usually left to the Prefects, the Tutor nevertheless had a strong influence on the atmosphere and character of the House, as our contributors attested.

Some Tutors were of the ‘old school’, particularly in the years just after the War. This was not surprising, since many had been teachers at Wellington since the 1920s:

‘I was in the Anglesey under the quiet gentlemanly Mr Hughes-Games, who one hardly ever encountered.’

David Trafford-Roberts (Anglesey 1943-45)

‘My Dormitory Tutor in the Anglesey was Mr Hughes-Games, a very gallant gentleman who had won two Military Crosses in the First World War. He must have been in his mid-50s; far too old and out of touch.’ Henry Beverley (Anglesey 1949-53)

‘Herbert Wright, my House Tutor, was always kind to me, but I think he was probably a bit too old for the job. If he ever had been willing to get deeply involved with young people, those days were long gone by the time I knew him. He and his wife promoted plays, in some of which I played quite prominent parts, although I now recall them only with embarrassment. That was the limit of his cultural endeavours for us. As was, I suppose, then customary, he left a great deal, almost certainly far too much, to the House Prefects.’ Peter Marshall (Stanley 1947-51)

‘Our Tutor was Mr Kemp who seemed to run the Dormitory through his Prefects, which seemed to work well. Occasionally he would have half a dozen boys down to his flat in their dressing gowns to watch television, a new and rather marvellous invention – black-and-white, of course, but warning us that it would soon be followed by colour. How right he was!’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

‘Most nights our Tutor, Mr Kemp, went round the Dormitory to ask boys how they were getting on. When he came into my room he always found me having gone to bed reading a novel and his invariable comment was, “My boy, why aren’t you working?”’ Richard Harries (Hill 1949-54)

Some were downright terrifying:

‘Mr Lewis was our House Tutor, fiery red hair and temper! He forced new boys to practise cricket by making us form a close ring round him and crack very fast balls at us to catch, or more likely to tear away to retrieve. He also built a “Tarzan” course in the nearby woods. Everyone had to climb and swing through the trees, and if too slow, do it again. Fortunately, I was in my element, but others not so agile had a terrible time.’ Peter Cullinan (Benson 1948-52)

‘Lewis had an obstacle course built in the woods opposite the Benson which, to a young boy, was terrifying, and I recollect that he used to get about ten of us, at 6.30 am, to scramble around this horror course. Another of his entertainments was to organise boxing in the House bathroom after Chapel on a Sunday morning, or in the evenings after prep during the week.’ Anonymous

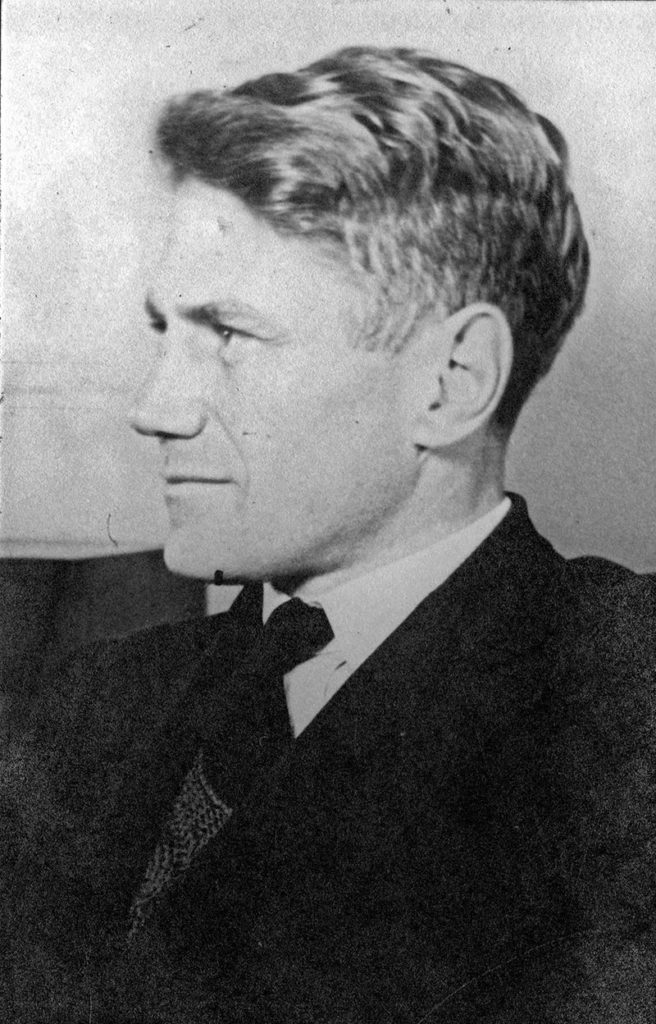

Lewis’ replacement was a teacher of equally long standing but with a very different outlook:

‘Lewis was replaced by C F G Macdermott as Tutor and he was such a charming and kindly man. What a relief!’ Anonymous

‘Mr Macdermott was extremely mature, experienced, dapper and caring, earning our respect.’

John Clarke (Benson 1949-54)

‘“Dermo” was my Tutor in the Benson and I remember him as a firm, gentle man who earned all of our respect and obedience – it would be hard to imagine anyone with a more suitable character to look after forty or fifty boys while they were out of their parents’ influence. He had an endearing habit, when you gained admittance to his study, of getting up from his chair and doing so with a sweeping, practised manoeuvre, pulling out the ‘v’ of his waistcoat to catch the monocle he wore for reading with his left hand, while extending his right hand to be shaken as he said “do come in.” I can still hear the steady tread of his foot on his nightly regal progress past our “tishes” during prep – courteous warning of the likelihood of his tap on someone’s door before opening it to check that all was well with the incumbent, or not, if the incumbent hadn’t heard the footfall.’ John Berger (Benson 1949-52)

‘Certainly Dermo made it his business to visit every boy every evening. These incursions are always remembered by reference to his looking over one’s work before allowing his monocle to drop free. The instinct to grab it was almost universal, though we all knew it was on a string round his neck. A mathematician, he would come into my room, raise the monocle and say, “Busy with your Greek?” Which almost always meant that I was working on some Latin. If my work was Greek, Dermo would enquire about the Latin. The misidentification was so unfailing that I believe he probably did it on purpose, as if to say that it was some alien topic as far as he was concerned.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

Douglas also recalled how Macdermott’s departure was marked:

‘We had a magazine in the Benson, a single issue to be passed round, called the Benson Rose. Tim Hunt, who was a good pal of mine, did an excellent cover at the time of the change of Housemasters. It showed Potter in his old Rolls with, at the time, four children, driving in one direction and Dermo on his bike going in the other. There was a poppy on Dermo’s bike – he bought one each year for Armistice Day and kept it in position for a whole year. Just a minor eccentricity but one that would resonate with those who were in the house at the time.’

‘Arnold Potter came with an adventurous reputation, having on occasion led groups of boys on expeditions over the roofs of the College buildings, and also ran the Wellington Boy Scouts Troop. He was generally very popular with the boys in the House and drove his large family around in an old open Rolls Royce, creating quite an impression. One incident I well recall is the occasion when the young Potters decided to upset their father by filling the car’s petrol tank with sand! This was a major disaster, of which I, for years, thought that Chris had been the ringleader, but much later his brother Hugh told me that it was he who should carry the blame! Arnold Potter was an excellent teacher and housemaster, but his study was always rather untidy. Once later on, when he was ill in bed for a short period, he said “Well Anthony, you can run the house till I am well again – just go into my study and you will find everything there”. Everything was undoubtedly there, but I well remember thinking that it would be almost impossible to find anything in the “deep litter” that confronted me!’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

Some Tutors divided opinion:

‘Our House Tutor, Mark Baker, was strict, rather aloof and gauche, with little sense of humour. He clicked his teeth often.’ John Michael Crumplin (Orange 1956-60)

‘Mr Mark Baker was Tutor at the time. I thought he was excellent in every way. I still have the long-hand letters, each running to two or three pages, which he wrote to my mother with each of my end-of-term reports.’ Robin Ballard (Orange 1955-59)

‘I followed my father into the Murray and liked my Tutor, Bob Storrar, very much.”

Ross Mallock (Murray 1954-59)

‘Our Tutor, R E Storrar, was not my cup of tea, as we were poles part in personality and interests. He displayed his lack of awareness of my extracurricular interests, in asking regularly about my progress in hammer-throwing, which was neither my event, nor was it one of the field events at Wellington. He was a kind man and I recall he allowed us to watch Billy Bunter on TV in his flat.’ Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60)

‘I had Bob Storrar as Tutor, who was totally accessible, and could come round our rooms, and have a private chat. If he wanted a totally private matter discussed, he would of course call us down to his study.’ David Simonds (Orange 1941-46)

‘My first Tutor, Bob Storrar, was a decent, serious, flat-footed, unexciting academic without charisma or, so it seemed, much time for us. He was uninterested in games, games players, or the athletic fortunes of the Orange – which were not great! He was remote, probably shy, and did not know us. His occasional visits to us in our “tishes” during evening prep were brief. The banality of our short conversations embarrassed both Tutor and boy. Only once did he stir me. One evening when we were marshalled for the weekly Dormitory prayers, some Biblical double entendre or the antics of an amorous maybug caused us to grin, then giggle, then laugh, then fall back into our “tishes” convulsed. Storrar, seeing our behaviour as disrespectful to him and a slur on the Lord whose message he was delivering, lost his temper. He stomped off down the dormitory shouting “You’re just a crowd of rowdies and a gang of toughs!” We were delighted with his accurate assessment and, more so, that he had actually noticed. For me, his outburst became a much-used catchphrase and source of pride.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

‘H C Marston was a quiet man who I got to know fairly well in private evening chats with him during my year as Head of Dormitory. He was a good listener and a good mentor.’

Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘I was very fond of Hugh Marston, a rather shy bachelor who lived with his old mother in Crowthorne and who was prominent in my athletics coaching.’ Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

‘As Dormitory Tutors went, Hugh Marston was truly dreadful. He adopted for himself a sort of SS officer’s demeanour. The Hardinge was to be the best at everything. We would play rugger harder and more mercilessly than anyone. Our watches would be set two minutes ahead so that we would be first everywhere and never late. We were discouraged from fraternising with boys from other Dormitories and Houses. When I joined a skiffle band called “The Blue Angels” made up of boys from the Blücher and Anglesey, he called me in angrily to ask why was this necessary. When I asked permission to attend the school dance, he barked, “Certainly not! Body clutching! Upright fornication!” He relented of course.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

‘I remember in bed at night being bitten by mosquitoes who bred in the College lake, which was very annoying, particularly the whirring noise the thing made prior to its attack, followed by the scratch-scratch to try to get relief from itching. I mentioned this to my Tutor H C Marston, who said he could not hear anything in his bed at night and implied either I was fibbing or they came to my bed because they were attracted by my bad smell.’ Anonymous

‘My Tutor was Hugh Marston. He was a fairly strict operator and a chemist by trade. He’d been an engineer during the War and it was rumoured that he still had some pieces of shell lodged in his backside, which accounted for his very occasional foul tempers. I got on well with him and mostly managed to keep him on my side in that he was very enthusiastic about all sports as they involved the Dormitory.’ Colin Mackinnon (Hardinge 1951-56)

While others were well-liked:

‘We were all fortunate in the Talbot to have “Nosey” Evans as our Tutor. He was a constant source of encouragement, understanding and good advice. A very kind man and highly respected, not least by myself. I remained in touch with him and his family until he died.’ Anonymous

‘Reporting to the family over one’s performance in term time was the responsibility of one’s House Tutor. Some were more diligent than others. The Talbot was fortunate to be in the wise charge of R G (Arge) Evans, and with a keen young undertutor in Dick Gould.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘“Nosey” Evans (nicknamed for obvious reasons) was relaxed at the end of his time; a generous and friendly Tutor, very much looked up to by me as a junior and full of witty asides such as: “no matter what you do the last drop always goes down the trouser leg!”’ Colin Mattingley (Talbot 1952-56)

‘My Dormitory Tutor was Mr Potter. He was a quietly-spoken man, friendly and well-liked. The Lynedoch flourished under him.’

Charles Wade (Lynedoch 1947-50)

‘I consider that I was very fortunate in having Phillip Letts (the Dingbat) and his wife Heather (Wombat), as Tutor. He was a very humane man and his wife took a special interest in the wellbeing of the “squealers”.’ Jerry Yeoman (Anglesey 1955-59)

‘Philip Letts; known by all as ‘The Dingbat’, from his cry from the rugby touch-line to “Go like a dingbat for the line!”. My abiding memory of the new boys’ tea is of the arrival of another boy and his large and hearty father, who hailed Letts across the room with a cry of “Bonzo you old bugger!” I never recollect our Tutor ever again being quite so embarrassed.’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

‘My House Tutor was Donald Parkes, who I liked and respected. He left the House Prefects to run the house, but knew more of our doings than he pretended, as I discovered when I became a Prefect and eventually Head of House.’ Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

‘The two Tutors of the Hopetoun during my time were M D Parkes (Mungo or Bloss), a somewhat avuncular figure but a first-class Tutor with the interests of his charges very much to the fore, and Peter Hincks, a shot putter of note (Olympic I think), who once exercised remarkable restraint over some appalling behaviour of mine.’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

Some made a strong impression, either by their enthusiasm or their interest in their charges as individuals:

‘Combermere with James Wort – very charismatic and competitive for the dorm to win interhouse sporting events, which occurred on many occasions.’ Mark Yorke (Combermere 1950-55)

‘The Combermere was a happy place, particularly after James Wort became Tutor. He was young, full of energy and ideas. Dormitory plays reached a high standard and became good fun. He started a Glee Club which I really enjoyed.’ Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941-45)

‘We were presided over by James Wort, a redoubtable, humorous, and encouraging master snuffling “Huthle buthle, Combermere!” on the rugger touch line; he stood out from his grey colleagues. It seemed to us that the Combermere was the only Dormitory where art, as well as athletics, was encouraged. This was a reflection of Mr (never James to us!) Wort’s skill in seeking out some accomplishment in each boy on which he could build self-confidence and achievement.’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘Jack Wort, preceded by a reputation as a madly enthusiastic driving force at the Combermere; a whirlwind, keen on everything, no member of House could escape his eagle eye and enthusiasm. The house had to be the best in College. He was undoubtedly an excellent House Tutor, dragging the Talbot out of its relaxed existence under the easy-going Evans to a hive of activity, excelling in sport in particular, but extolling being first in academic achievement, and taking part in all areas of College life… music, singing, art, poetry, plays and so on. Everything was to be approached to win. He was most successful in transforming the house into a hive of rewarding activity.’ Colin Mattingley (Talbot 1952-56)

‘Our Tutor Rupert Horsley was, for our early years, somewhat remote, but he was a kindly man. In more senior years, he would invite us to listen to music in his part of the House. In the term when the Picton put on Hamlet in the Theatre, he took a couple of us with his wife to see a production in Stratford, with Judi Dench as a young Ophelia.’ Robert Hirst (Picton 1955-59)

‘I had tremendous respect for Mr Horsley who offered me and many of my colleagues a great deal of guidance and encouragement to do their best, and in my case to give more than I thought possible in various sports that I felt interested me. He and his wife took me to Hambleden Lock on the Thames where he set up his stool and easel on the weir and proceeded to paint a picture whilst his wife took me for a walk beside the river. I especially enjoyed their kindness as my father had been posted to BAOR, so my parents were absent and I was usually not able to go away for exeats at weekends.’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954-59)

‘Tutor Rupert Horsley was excellent, and he and his family became my lifelong friends.’

John Stitt (Murray 1940-45)

‘Rupert Horsley was a very good Tutor and I was very fond of him. Under him, games flourished and Picton in my last year was in every cock match, usually against strong opposition from Combermere.” Bertram Rope (Picton 1949-54)

And some were simply eccentric:

‘During prep, we dreaded hearing the footsteps of our Tutor, M M Reese (“Gaffer”) who would walk in to see what we were doing and, whatever it was, it had better be done well. We had a healthy respect for Reese and it did not do to cross him.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘“Gaffer” Reese ran the Hardinge with a light touch, giving the prefects considerable authority. His presence in the Dormitory was always advertised by the smell of pipe smoke, and when today I come across an increasingly rare pipe smoker, the smell takes me straight back to my days at Wellington seventy-six years ago.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘For my first year or so the Hardinge Tutor was “Gaffer” Reese, an expert on the Tudors and Stuarts. He was an eccentric man, and had his own humorous type of vocabulary. For instance, observing any boy carrying a music case, no matter whether for violin, cello or flute, he would remark, “Trumpeting, boy? Trumpeting.”’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘My Tutor when I arrived was Denby. He was a rather sad bachelor. I remember him saying to me, “If you want to get married, don’t leave it too late.” After him came Anthony Crawley, known as “Actually Factually” which was one of his favourite expressions. He was a rather languid gentleman, very nice and always helpful.’ Allen Molesworth (Blücher 1945-48)

‘The Tutor throughout my time was the legendary Anthony Sebastian Crawley – ASC – I can still forge his signature! He was a delightful eccentric but also a very level-headed and fair-minded tutor.’ Bryan Stevens (Blücher 1948-52)

Dormitory staff

Lower profile than the Tutor but equally important, domestic staff made a vital contribution to dormitory life. For the majority, particularly those in dormitories, the key figure here was the ‘jally’, who not only served his young charges at the dining table, but was also responsible for cleaning and tidying the dormitory.

‘We had a “jally” who looked after the rooms, made the beds and emptied the chamber pots!’ Nigel Gripper (Hopetoun 1945-49)

‘Each dormitory was cleaned by a “jally”… Ours was a silent, handsome, long-suffering and charming man called Austin – which was his surname. And we called him Austin, and we treated him rather poorly – because our predecessors had and we knew no better. He cleaned our “tishes,” made our beds, emptied our chamber pots, polished our dormitory passage, and sorted out our small two-bath washroom on the first étage of our tower. Where and how Austin disposed of our nightly effluence, I know not. But he did, and his unobtrusive care for our welfare and his impact on our general well-being was immense but, sadly, largely unnoticed. Some other jallies including the Blücher’s Ernie were noisy, quite underwhelmed by their charges, rude, amusing and often critical. Some were known by their first names. All, to a lesser or greater extent, were “characters” and constituted a major strand in the rich tapestry of life at Wellington.

When I was Head of the Orange, I once addressed Austin as “Mr Austin.” He was shocked, and disconcerted. When I invited him to come and watch the Dormitory play in some quite important rugger match, he seemed affronted that one of his young gentlemen was showing dangerous signs of socialist egalitarianism. Austin was tipped at the end of each term, but by then our pocket money was very much depleted and, as few of us were prudent enough to reserve a slice of our resources for dear old Austin, I guess he did not get anything like the reward he deserved.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

Female influence was generally lacking at Wellington, but not completely absent. The difference which could be made by a House Tutor’s wife has already been noted by some. Another motherly figure, particularly in Houses where they were perhaps more common, was the Matron:

‘A resident Matron kept one’s clothes in order and a check on health.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘A great refuge in a storm, if or when there was a need, was Matron in her own small room on the ground floor. Through much of my time that was Peggy D’Arch Smith, a wonderful war widow who was so good to us all…’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

John Berger (Benson 1949-52) summed up the invaluable contribution of these College servants, and how they were viewed: ‘Looking back, I am sure that we were blessed by the husband-and-wife team who sorted out all our domestic needs wonderfully efficiently and almost wholly unseen – and without thanks or praise from we unthinking students of those days.’