CCF: Corps Life

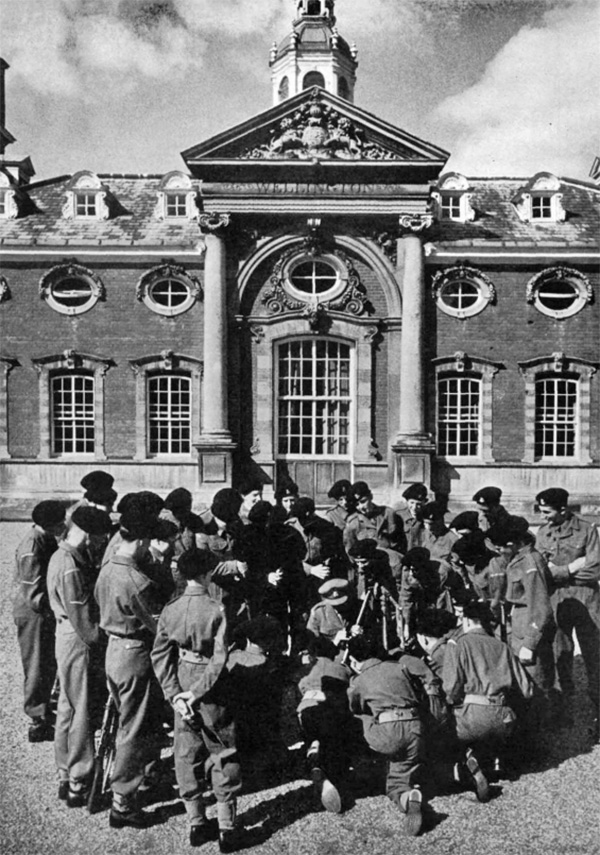

Membership of the Combined Cadet Force, or Junior Training Corps as it was previously known, was to all intents and purposes compulsory for Wellingtonians of the 1940s and 50s. Accordingly, all our respondents had memories of it, whether good, bad or indifferent.

For many, it was a positive experience:

‘I fiddled my age to get into the Corps a term early. I loved it, and, apart from attending each of the summer camps, I went on several holiday attachments to Regular Training Establishments in the area. The majority of boys at Wellington professed to regard the Corps as a joke or were even openly contemptuous of the whole set-up. Nevertheless, the Corps operated with surprising efficiency and good military order.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘Being quite good at its activities, I enjoyed the Corps and attended Corps camp for a couple of years. As one of the five CSMs I enjoyed the smartness of drill, and teaching the ability to take apart and reassemble the Bren gun blindfold to simulate darkness.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘I was 14 years and three months old when I joined and I enjoyed it greatly. I learnt a great deal and became very adept at field craft, map reading and the like. I loved the strategy and planning part of things too.’ Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53)

‘Yes, this was fun, and I ended up being RSM of the CCF. As a “new boy” I was amazed to receive on my first day a rifle handed to me to look after for the whole five years. These were stored, under chain and keys, in the Armoury.’ John Le Mare (Stanley 1950-55)

‘Corps was great fun and very useful skills – shooting, knots, first aid etc.’

Robin Lake (Benson 1952-57)

‘I thoroughly enjoyed the Army Section. It was welcome distraction from regular College life and apart from spit-shining boots and blancoing canvas, we all looked forward to those Wednesday afternoons.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

‘I very much enjoyed Corps and indeed as a result seriously considered going into the Army. I ended up being a CSM, so fairly senior in the rankings. I particularly enjoyed weapons training and shooting the various weapons on the range – in those days 303s, Sten guns and Bren guns. As one became senior you could join what was called “Junior Leaders” and we were put through some quite tough tasks.’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58)

Almost everyone could remember to which rank they rose, or failed to rise, although few could match this story of how their promotion was achieved:

‘I was a sergeant in the Corps. To gain my promotion, I went on a course in the holidays at the Police Training College in London, fell out of a tree hitting my head on a steel bin, went to the Septic Military Hospital and was put in the syphilitic ward… I was sent to surgery for a septic leg, but luckily it was noted that I wasn’t syphilitic just in time and I was returned to the ward unharmed and did eventually get my forehead drained. Three stripes well earned?’ John de Grey (Blucher 1938-43)

Others were less enthusiastic about the Corps and what it entailed:

‘All I remember is long marches with a heavy rifle, and “The first three letters of ‘management’ are ‘man.’”’ Dick Barton (Lynedoch 1938-42)

‘We were issued with a peaked cap, and a uniform with a great many brass buttons which had to be cleaned with Duraglit.’

Peter Bell (Blucher 1943-48)

‘Blanco and Brasso were king, together with the ability to polish boots to a mirror-like finish; not to mention being able to iron the necessary creases on the back of one’s serge blouse or jacket, to the exact regulation lengths – the main difficulty being with the irons. They were not as known today; they were flat-irons, heated on gas-rings at the end of the dormitory, until reaching the required temperature. Judgement of this was dodgy – one spat, and if it sat and sizzled, okay; but if it leapt off, too hot, and even through the ubiquitous brown paper, the serge was in severe danger of scorching, requiring delicate work with a razor-blade to scrape off the burn-marks.’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

‘As a timid young person who disliked shouting and physical exertions on things like assault courses, which were beyond my capacity, I detested the Corps, although rather to my surprise, as a National Service officer after leaving Wellington, I became easily reconciled to the army.’ Peter Marshall (Stanley 1947-51)

‘Initially I had little enthusiasm for the Corps, with its basic infantry training (“kitten crawl and “bushy-topped tree”) and the hour of drill in “mufti” which took place on South Front each Friday morning. The termly Field Day exercises in an army training area were not taken seriously. But I became more engaged when with sergeant’s stripes I attended one summer camp in tents on Salisbury Plain and also took over the more adventurous Junior Leaders cadre.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘The same disadvantage, growing no taller than 5’2”, presented itself during my time in the Junior Training Corps as the standard 303 Lee-Enfield rifle, apart from its weight, was far too long for me to manage properly, especially on field exercises.’ Anonymous

‘The Corps was a bore. I was a corporal and found it heavy going. It is interesting that our rifles were Lee Enfield 303s made in 1916!’ Bertram Rope (Picton 1949-54)

‘There was rather too much drill and “bulling” of kit for my taste, but again it kept my unruly spirit in some sort of order. I did enjoy the annual Field Day, and have a photograph of myself with rifle accepting the surrender of some of our dastardly foes.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

‘I did not greatly enjoy it, and it was a sign of the prevailing attitude that when the news came through that we had been beaten at a Field Day by Charterhouse, everyone cheered.’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘It was all rather silly really, though we did our best to take it seriously. Many futile hours were spent in polishing toecaps with a product called Heelball, and blancoing our webbing. One not good memory: having to go through a nasty muddy tunnel under a nearby bridge holding our rifles above our heads, and being put on a charge if we got them wet. It was known as “Doing the Sewer.”’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

‘I thought it was ridiculous to spend the week bulling my boots and then crawling through a sewer on a Wednesday afternoon. To me it was a pointless activity without any meaning.’

Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953-57)

Although there were some entertaining moments:

‘… such as when a drill instructor from Sandhurst commented on the oversized uniform of one of the younger members, “If you was in the Women’s Royal Army Corps you would be going on sick leave.” Mine clearance also provided a bit of light entertainment, in that when the dummy mines buried in a sand bed were probed too enthusiastically, a skeleton hanging at the end of the bed danced. Needless to say, the temptation to probe too hard was irresistible.’ William Field (Lynedoch 1952-56)

Whatever Wellingtonians may have felt about the Corps, very few made overt objections to it. We received only these very few accounts of dissent:

‘There was a Corps mutiny resulting in a full Corps parade on South Front, taken by the school RSM Colin Innes. It was not a good move and he soon regretted calling it!’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

David Ward (Hopetoun 1954-58) was our only recorded conscientious objector, although one longs for more detail in his simple statement: ‘I refused to join the CCF which caused a bit of a kerfuffle.’ We do, at least, have his brother’s point of view on this event:

‘We were all “invited” to join (in theory voluntarily), and most did so without demur until my younger brother declined in 1956, causing something of a stir – I was summoned from Sandhurst and told to persuade him to change his mind – of course I didn’t/couldn’t!’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

Officers and staff

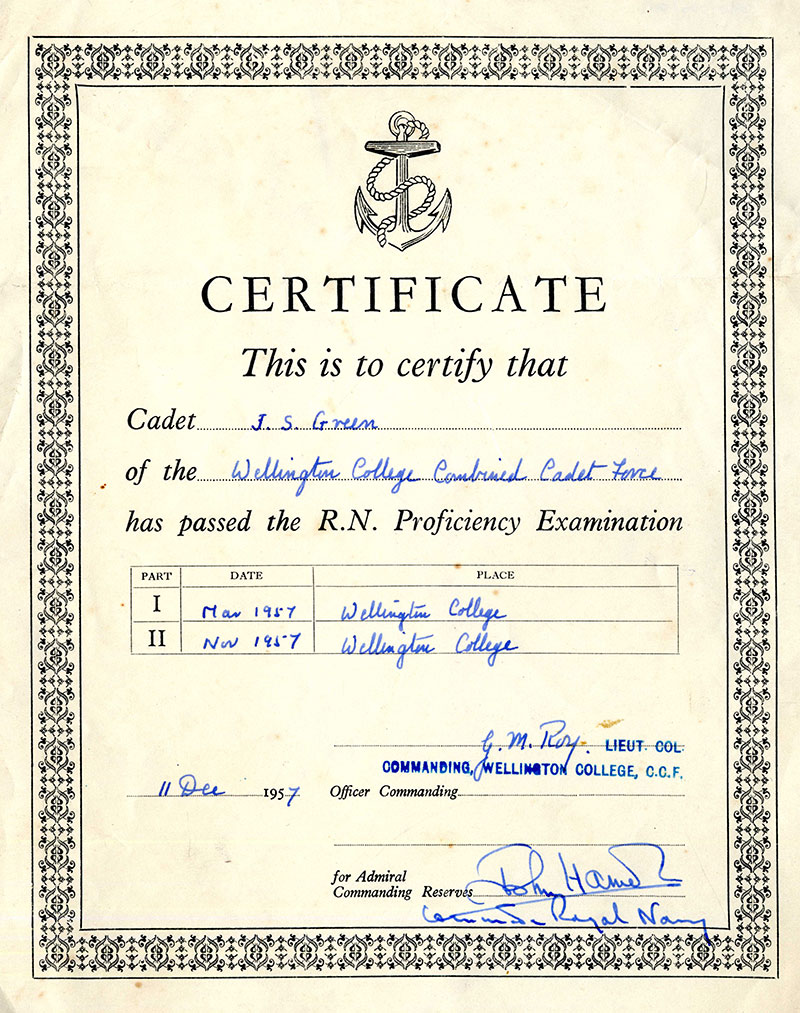

The Commanding Officer of the Corps from 1940 until 1946 was Major Macdermott. He was followed by Colonel Roy, who held the position throughout the 1950s. For reasons that were not entirely clear, he was nicknamed ‘Hoch’ or ‘Hosh’ and was widely remembered. He is also discussed on the page about Maths teachers.

‘Colonel Roy was in charge of the Corps and I remember an occasion when, confronted with a particularly idle bunch of cadets, he became exasperated and bellowed “Men that mutiny get shot!”’ Neil Munro (Talbot 1952-56)

Several other teachers had roles in the Corps and also sparked memories:

‘I remember learning how to pick up the rifle on South Front. Down I went and rose with the weapon still on the ground. Sandy Entwisle was watching. “Douggie,” he said, “I think you will find it easier if you take your gloves off!”’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘One had to go into the Army Section first – fieldcraft with Ned Catterall, a former Chindit: “Down behind your individual blades of grass, ha, ha, ha.”’

John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

For many years the Commander of the Naval Section was ‘Dick’ Borradaile, inimitable and respected by all; he ‘had a characteristic way of pronouncing “if” as “eev”,’ according to Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952-57). Another popular officer in the Naval Section was ‘Charlie’ Kuper, described as ‘a splendid, rumbustious sort of chap who used his influence to organise some wonderful camps and field days for us.’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56) recorded a memory of one of the Armoury staff:

‘The Armoury was situated beside a soccer pitch and required two proper (or possibly retired) soldiers to look after it. Goodness knows what they did apart from issuing rifles on a Wednesday afternoon and possibly for the parades on Friday mornings. One of these men was called Salmon. He lived in a house about fifty yards from the Armoury. Somehow, and I struggle to think how, I and another boy found our way into Salmon’s house to watch television [still a rarity in the 1950s]. I suppose we were watching Wimbledon or a test match, and I well remember having the cheek to turn up again the following week to seek re-admission. Word got out that this was happening. Perhaps poor Salmon spoke to someone, and there was an announcement that the houses of the Armoury staff were out of bounds to us. I rather guess they always had been. Or it was so obvious that it didn’t need spelling out!’

Drill

Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47) recalled that ‘The training was largely practical and worthwhile with (unlike at RMAS later on) comparatively little square-bashing.’

Perhaps for this reason, we received relatively few stories relating to drill, although it obviously made an impression on some:

‘Drill was tedious but led to a presentable standard at the Annual Inspection, which culminated in a march past the Inspecting Officer preceded by the memorable hoarse words from our commander Major Macdermott: “Wellington College Officer Training Corps contingent will march past in column of fours led by A Company followed by B Company followed by C company followed by D company followed by Band – by the right – Quick March!” Try shouting that in one breath!’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘My difficulty was that I had, and still have, some difficulty in determining my LEFT from my RIGHT.’

John Hornibrook (Murray 1942-46)

‘I ended as Regimental Sergeant Major – mainly because I could shout loudly and with authority.’ Sam Osmond (Hill 1946-51)

‘The shambolic drill in our scarecrow denims was a bore. Somehow, I became the Signal Sergeant which allowed me to hang around the Armoury and miss the drill.’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

Field Days and other exercises

Field Days were mock battle exercises, usually carried out against an ‘enemy’ represented by another school’s Corps.

It was not surprising that these occasions produced a strong competitive spirit and occasionally, some dirty tricks:

‘I remember vividly one of the Corps Field Days when we were pitted against Eton. The field of battle was Barrow Hill. Eton’s Corps was much larger than ours… Accordingly, we were positioned atop the hill and tasked with its defence. So lots of booby-trap wires were set and blanks loaded in our rifles. Then came the attack which was on a broad front and very ferocious on both sides. It ended up with hand-to-hand fighting, blanks being fired off like mad, some at almost point-blank range and to cap it all the Brigadier appointed as referee, who tried unsuccessfully to keep control, was de-bagged and tied to a tree! This episode resulted in a permanent ban on any repeat Field Day contest between the two Colleges.’ Anonymous

One particular tactic was recalled by several respondents:

‘A Field Day was planned with St Paul’s. The intention had been a friendly mock battle between the two Corps. But when the authorities discovered that we had all been collecting pencil stubs which, when fitted ahead of a “blank,” made our rifles potentially lethal, the event was promptly cancelled!’ Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47)

‘The fun was on Field Days, trying to fire pencils with our blank cartridges from our ancient Lee Enfield rifles.” Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

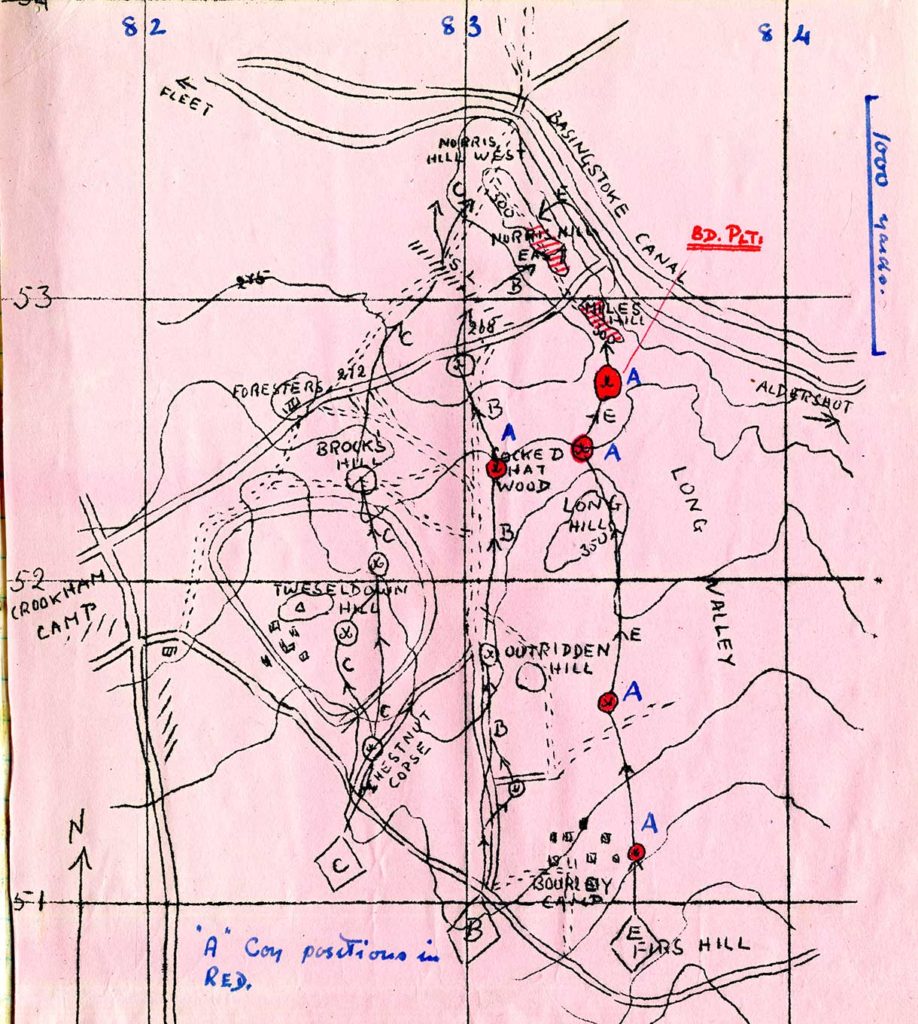

‘Field Days against Charterhouse had become quite serious, and we were advised by our NCOs (College boys) to put pencil stubs down the barrels of our rifles which would whizz out as one fired blanks and could easily have taken somebody’s eye out. Not surprisingly this frightened us younger boys no end. After two years of this we didn’t engage with enemy in this way, only with each other, and we endlessly leopard-crawled our way through the fly-ridden bracken of Tweseldown in platoons.’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

Those who graduated as Junior Leaders in the Corps had to undertake a special night exercise, as Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61) described:

‘I remember the night exercise well, and not unhappily. Small squads each of four or five boys were dropped off, from army lorries, about 10pm at scattered unfamiliar locations some miles from College. We were armed with an OS map and given a map reference to which we had to proceed and arrive at by a certain time, next morning. All the squads would be heading for the same destination, situated on an army training ground, moving in from different points on the perimeter of a wide area. I recall that my group was dropped off in the midst of a residential area and most of our route involved moving along roads between various villages or built-up communities. This was not unenjoyable, it was a dry night, but I wonder how it would be viewed in today’s politically correct climate? Each boy, in khaki with webbing kit and faces blackened with burnt cork would be carrying a .303 rifle; in the dark of night in residential areas; startling when households would be drawing their curtains before retiring!’

Not all those on exercises were so successful:

‘My highlight was getting lost with my squad around Sandhurst and running out of time to get back to College. A decision was made that we should give up and phone for a taxi. We knocked on a door and persuaded the owner to make a call on our behalf. The taxi driver duly appeared but had not been warned about our state of dress. Luckily, after the initial shock he saw the funny side and dropped us back in College grounds before the deadline.’ Adrian Stephenson (Talbot 1957-61)

Field Days made an interesting change from the routine of life at Wellington and, as such, were often described by boys in their letters home. We were fortunate to receive two examples of these, one from the beginning of our period, the other from near the end:

‘We marched to Caesar’s Camp as usual, it was the most awful day possible for it, with a continual heavy drizzle coming down, and it was icy cold. Caesar’s Camp is just one great expanse of undulating earth, with an occasional stunted tree and patches of sodden dead bracken. On that day the rain had turned the earth into deep oozing mud, and that was the country we had to operate in.

I was in the ‘O’ Group, which was the Platoon Headquarters and had to keep in touch with the sections around it and direct the attack. But there was some hitch in the proceedings – goodness knows what – with the result that the whole dormitory platoon had to wait for about twenty minutes in this drizzle of rain, standing in the deep mud and absolutely icy in our dripping clothes. We did actually win the attack in the end, which was some consolation.’ Peter Bell (Blucher 1943-48) in a letter from November 1944.

‘On Field Day, we were taken by coach to Camberley. We spent the day either dashing around or sitting about waiting for something to happen. At one point, two people ran into us and we caught them. Later, we advanced on two others who dropped their rifles and fled. We shot at them using blanks, and so gained more points.

At the end of the day, Major Willey and Captain Gould had a fight and a huge ring of boys formed around them. Everyone was shouting and pushing. Captain Gould won and a thunderflash was thrown into the crowd to break it up. Major Willey and Captain Gould were covered in mud.’ Anonymous, 1957-60

We also have Gould’s own account of this incident in his memoirs, later donated to Wellington. They suggest that the fight was not quite as serious as the boys perceived:

‘One day Gerry Roy organised a Field Day… Peter Willey commanded half the boys in one “army,” and I the other half. We had a lively time and were near the Farm when Cease Fire was blown. We shook hands but then both claimed victory, so I challenged him to settle the issue by single combat. We had a long wrestling struggle, loudly cheered on by our respective forces. We agreed on a draw! The news of this spread through Common Room, and I was censured by some for compromising the dignity of the staff. Maybe I did, but I think no harm was done!’

Corps Camp

The annual Corps Camp was held in the summer holidays. Some Wellingtonians did not wish to participate:

‘I felt neutral about CCF obligations, with the exception of Camp which I was determined not to attend. In fact, each spring holidays when the Blue Roll arrived through the post from College, I was quick to extract the enclosed letter asking parents if their boy should attend Camp.’ John Watson (Benson 1946-51)

Those who did attend, however, had some vivid memories:

‘Tented camps at Warminster, where Gerry Roy would throw thunderflashes at all and sundry and we on the march would sing the old army songs – I Don’t Want to Join the Army, The Quartermaster’s Stores, etc. Never forgotten was Gerry Roy, standing stark naked in an aluminium washing bowl in front of some twenty tents, with a hundred astonished young eyes looking on.’ ‘Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

‘On one camp in Norfolk, we had been out on an all-day exercise with various other schools’ Corps and it was pouring with rain and muddy. A number of lorries had been laid on to take us back to camp, but there were not enough of them. So our Commanding Officer [Roy] decided to let the other schools go and as the Wellington contingent was the largest, he announced loudly for the benefit of all “Wellington will march!” And so we did for the six miles or so back to camp!’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

‘I went on one annual camp which was tough and sometimes scary. We were camping on Salisbury Plain and had to do a night exercise which required us to get from A to B, but we were told there the “enemy” – regulars from the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment – were marauding around the countryside aiming to capture us and interrogate us. We made sure we didn’t get caught.’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58)

‘The various exercises were exciting, not so the washing up. Lukewarm water, little soap and few dishcloths, and after greasy stews – yuk!’

Randal Stewart (Anglesey 1953-56)

‘At Corps Camp at the age of 16, loosed on cider – I have never drunk it since!’ Charles Enderby (Picton 1953-57)

‘I attended two Summer CCF camps in Snowdonia in Wales. Being wet and mud-covered 24 hours a day for 10 days was a bit of a burden, but the rock-climbing was thrilling. After camp, we took the train to London and I, still in my grubby denims, popped in to see my youngest sister Virginia who was receptionist at a very swanky interior decorator. I thought she’d be surprised and tickled to see me, but on sight of my denims, she shrieked, “Oh you disgusting little boy! Get out of here!”’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

Preparation for National Service or a military career

All those at Wellington during the 1940s and 50s knew that their school years would almost certainly be followed by a period of active service, in either the War or, later, National Service.

Many hoped for a longer military career, often following family tradition. So, were their years in the Corps a useful preparation for this? Most thought so:

‘The basic soldiering that we learned in the Corps proved to be of considerable advantage when we were called up for National Service… Unlike most of our fellow recruits, we knew the basic drill movements and were well-versed in blancoing web equipment.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘At that time, the Korean War was in progress and I remember thinking that what I learnt in the Corps might be of more practical value than what I learnt in the classroom! Anyway, it did prove its value when I started National Service.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘I found discipline far tougher in the real forces than in the make-believe forces at Wellington, particularly because my public school accent seemed to cause real world NCOs to take delight in making my life hell and their utilising swear words and expletives beginning with B… or F… to make me aware they considered my personal failings were disgusting. Parade ground drill in the real forces was also far stricter than it ever was in the Corps at Wellington.’ Anonymous (1950-53)

Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53) found his experience in the Corps useful in many ways:

‘Oddly enough, of all the skills I learnt at College, it was these military skills that served me best in later life. Planning became very useful when organising plays, doing geological fieldwork or running societies. Map reading became valuable when trying to find my way around in the Canadian forests or looking for archaeological sites in Egypt, South Africa and Turkey. I used my shooting skills when threatened by bears in Canada. Then, when I was doing basic training in the RAF, I was able to help other recruits who had no experience in drill. The strategy part helped me when I got involved in corporate planning and other activities.’

John Green (Talbot 1954-58) explained how things changed in the late 1950s:

‘To be assured of a place in the Navy on one’s National Service, one had to pass the Petty Officers exam, which I managed to do, and in my last year was a Petty Officer in the Naval Section… Being thus armed to face the future, National Service was abolished for those born after 17th January 1940, and therefore with a birthday of 2nd March, I missed out on an experience I think I would have enjoyed and for which I was well prepared.’

But those who chose to join the forces still felt the benefits:

‘The hours of square bashing and bulling of equipment stood me in good stead for when I joined the Territorial Army, the most lasting benefit however being a love of and a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of Ordnance Survey maps.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

‘It was during the quite horrendous first term at Sandhurst that I appreciated the military aspect of life at Wellington and the very good preparation it had given me.’ Jerry Yeoman (Anglesey 1955-59)