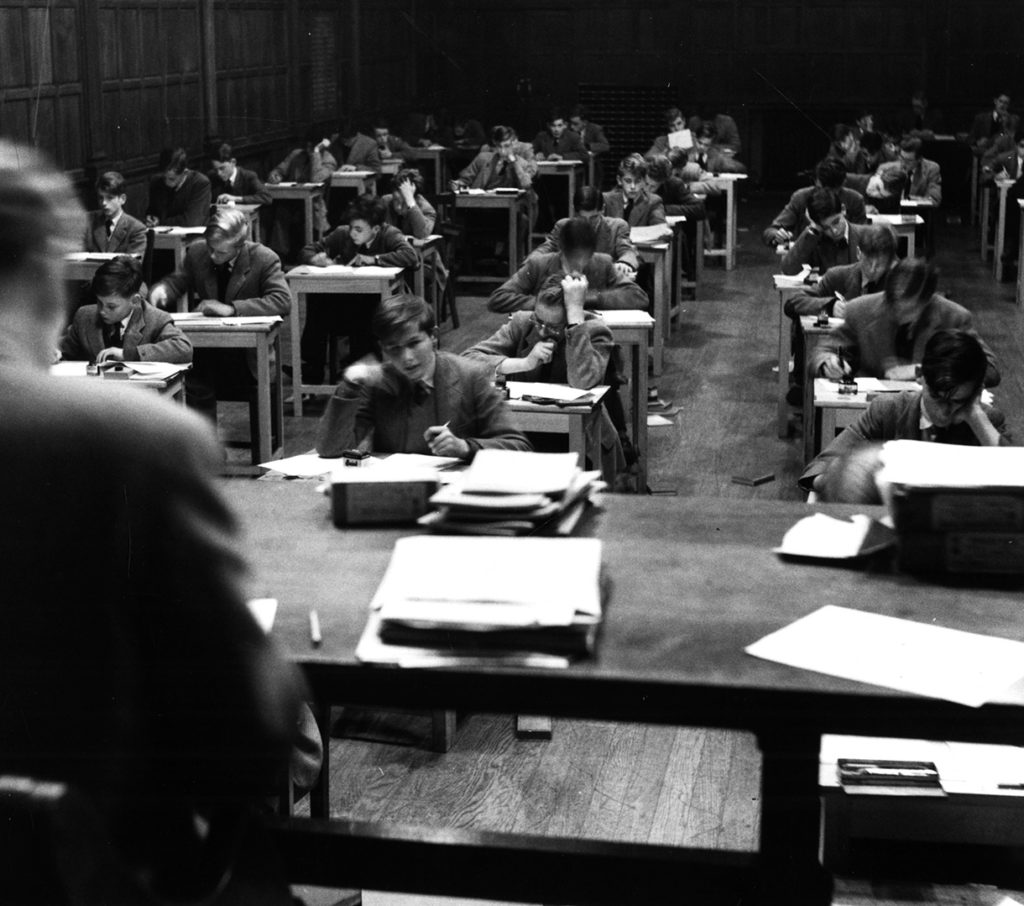

Academic Expectations

Probably very few Wellingtonians reflected much at the time on the school’s academic ethos, the quality of their teaching or the factors which influenced these. Many years on, however, mature reflection and hindsight enable them to comment thoughtfully and insightfully on these subjects, although by no means do they always agree.

Academic standards

Many Wellingtonians of the 1940s considered that the school held reasonably high academic standards during those years:

‘Educationally, the Wellington Common Entrance was considered the second hardest after Winchester.’ Leslie Bond (Lynedoch 1948-53)

‘Wellington’s Common Entrance examination demanded a reasonable standard of education. Wellington had a higher standard than, say, Eton, and some boys who failed to get into Wellington had to seek for education at lesser schools.’ Ian Nason (Orange 1950-54)

‘Harry House had the admirable policy of hiring staff who were budding academics, but unfit for military service. They joined similar academics appointed by Longden. The result was a flowering of the arts and theatre, and a rather arrogant clique of “intellectuals,” who “used to carry slim volumes of TS Eliot around with them wherever they went.” This was perhaps not what one might expect from a school like Wellington so long ago. Later, some of them had success in the arts. An outsider might have expected the War and its aftermath to have been a dark age for Wellington. It seemed to me to be a golden age. After the War, when the regular teachers came back, I felt that something was lost.’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘I was fortunate to arrive at a time when teaching standards were improving with a cadre of dedicated schoolmasters who had returned to teaching after demobilisation. They also brought a creative spirit to the school’s cultural and academic life.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

However, some students from the 1940s and ‘50s felt that standards had not been high, and teaching not particularly good:

‘Wellington academically: pretty low, or I would never have got in! Marlborough was considered much better in those days.’ Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47)

‘College’s culture of 1950 was muscular (rugger), military (lots of Army sons and recruits for Sandhurst), almost indifferent to matters academic (it felt like that anyway).’ Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53)

‘I am sorry to say, educationally, Wellington was not a good school, but the greatest of fun, and, from that point of view was rather a waste of my father’s money.’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘The quality of my teachers, almost without exception, I recall as being poor.’ Nick Harding (Combermere 1951-1955)

‘Teaching was benign, to the point of not pushing enough.’ John Flinn (Combermere 1944-49)

‘I look back with a feeling that most teachers were competent, but few went beyond this.’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘(There was) no real attempt to show boys how to learn or why it was important.’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

‘I learned very little. I liked most of the ushers, but none stimulated in me any sense of curiosity or appreciation of the value of learning. In the classroom, the main goals were fun and mischief. Much more fun than studying and learning was making toast with a candle in the back row of the class, or with pencil and sharpener held aloft asking for permission to go to the lavatory hoping to elicit the answer, “Do it in the waste-paper basket and don’t make a mess.”’ Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54)

‘Wellington, during my time, was not an academic school. Beautiful buildings and grounds with a great history and tradition, but not academic. My grouse is that I was never taught how to concentrate and study subjects that did not interest me. I was, I think, an average student. I needed to be inspired and motivated. (And) if not inspired, then taught the need to buckle down and learn how to learn. For us, those who did (well) were “swots,” not bullied, but perhaps pitied for not joining us in whatever we were doing.’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

‘When I went to Wellington, it was not, I think, regarded as a top public school and was not that well known. When I told people where I was at school, they asked whether it was “the school in Somerset” or “the school for potential Army officers?” It was not well endowed. It attracted mostly children of (the) professional classes and was not academically in the top flight. Nevertheless, it was much respected by those who had connections with it.’ John Thorneycroft (Benson 1953-58)

Some respondents took a more nuanced view, commenting on particular educational aspects offered, or on attitudes towards learning:

‘I was very much General Sixth… This suited me as it meant subjects, such as History and Maths, would be taught by the inspirational masters of the time. They opened doors to one’s imagination and there was no forcing the pace to cover a curriculum needed to get into university. I think College opened the minds of those not so destined, as there was time to do so in a less taxing curriculum… There were plenty of role models amongst the staff willing to help if you were prepared to engage with them. Nevertheless we were expected to make the running, which meant those who chose not to could pass through College in a gentle meander, not bothering to get much from it.’ Colin Mattingley (Talbot 1952-56)

‘Wellington was considered a college which encouraged leadership and an ability to fend for one’s self, not especially academic like Winchester College, for example.’ Ian Nason (Orange 1950-54)

‘Wellington was not a school noted for excellent examination results and I never felt pressure to achieve academic miracles… I would describe the school’s objective more as assisting the pupils to make the best of the talents they were given.’ Richard Merritt (Picton 1954-59)

I think we were not well-prepared for exams. For instance, I don’t remember sitting “mocks.”’

Christopher Miers (Beresford 1955-59)

‘It is difficult to comment on the standard of teaching overall. Monotonous is the word I would choose. Wellington did well in Classics, History and the Arts. It gained university entrances in these subjects as well as many entrances to Sandhurst.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

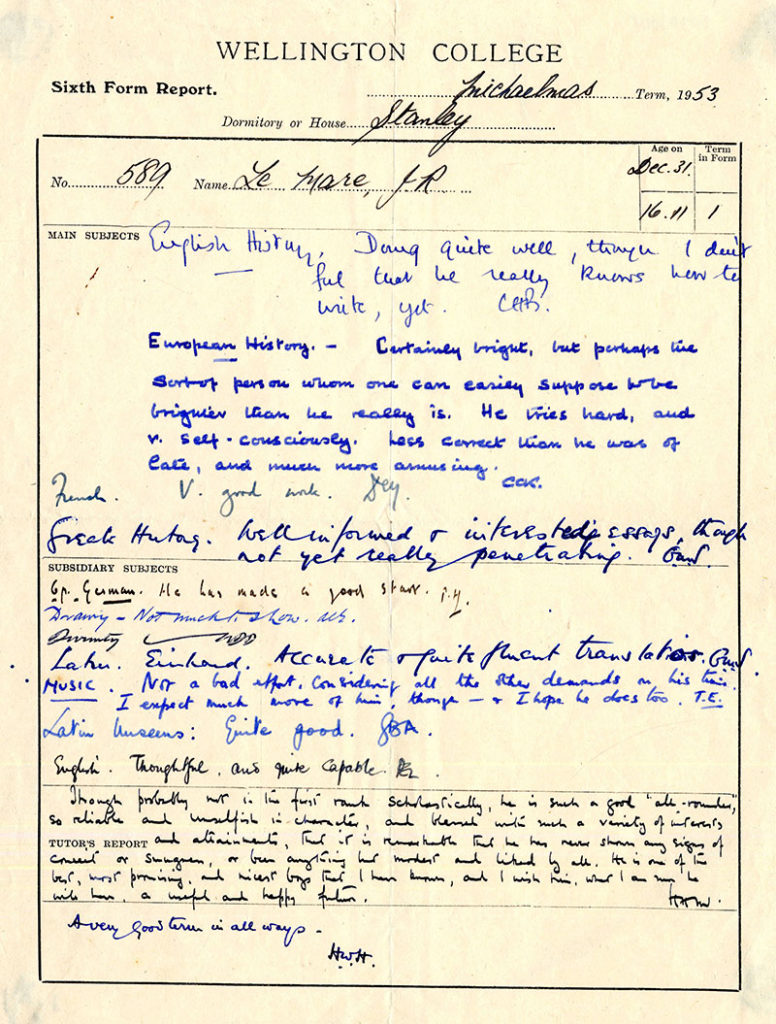

‘Whatever it may have been for the great mass of boys, Wellington in my time, was, presumably for a small minority, an intensely academic school. If you showed an early aptitude for a subject, you would be taken up, carefully nurtured, given highly specialised teaching in a small group in a narrow range of subjects – I was told to abandon all scientific and mathematical efforts beyond basic school certificate maths; all this with the ultimate aim of winning a scholarship at an Oxford or Cambridge college. This was a kind of pedagogy that would not now meet much approval, but it suited me fine.’ Peter Marshall (Stanley 1947-51)

‘No doubt the standard of education for the brighter pupils was excellent. For those of average intellect, like me, I don’t think the system got the best out of them.’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58)

Several commented, with hindsight, that teaching methods of that era differed from today:

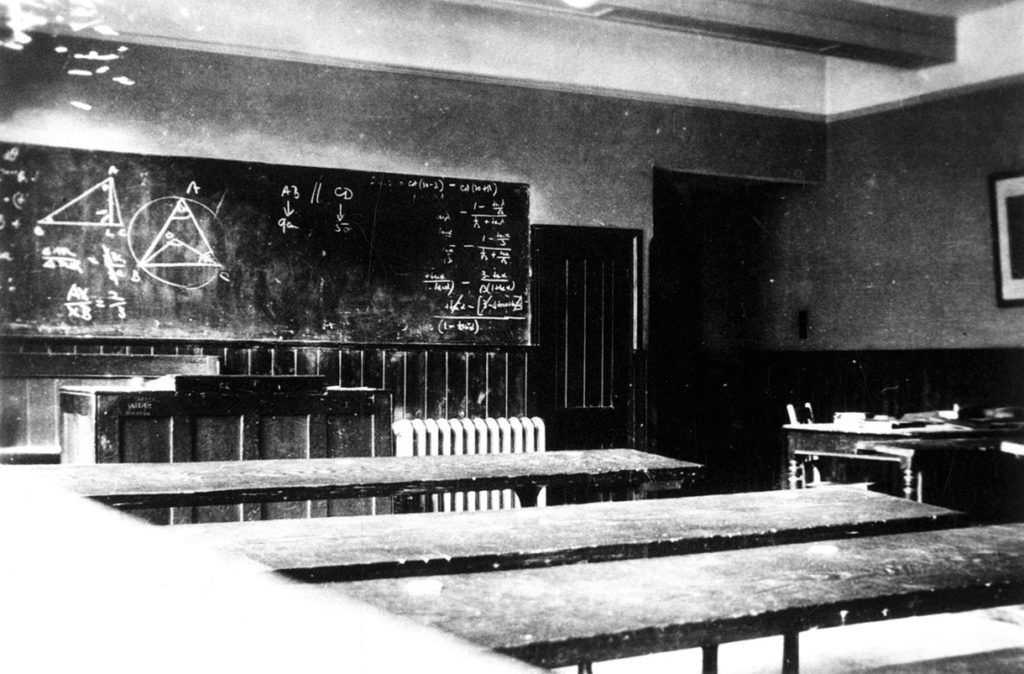

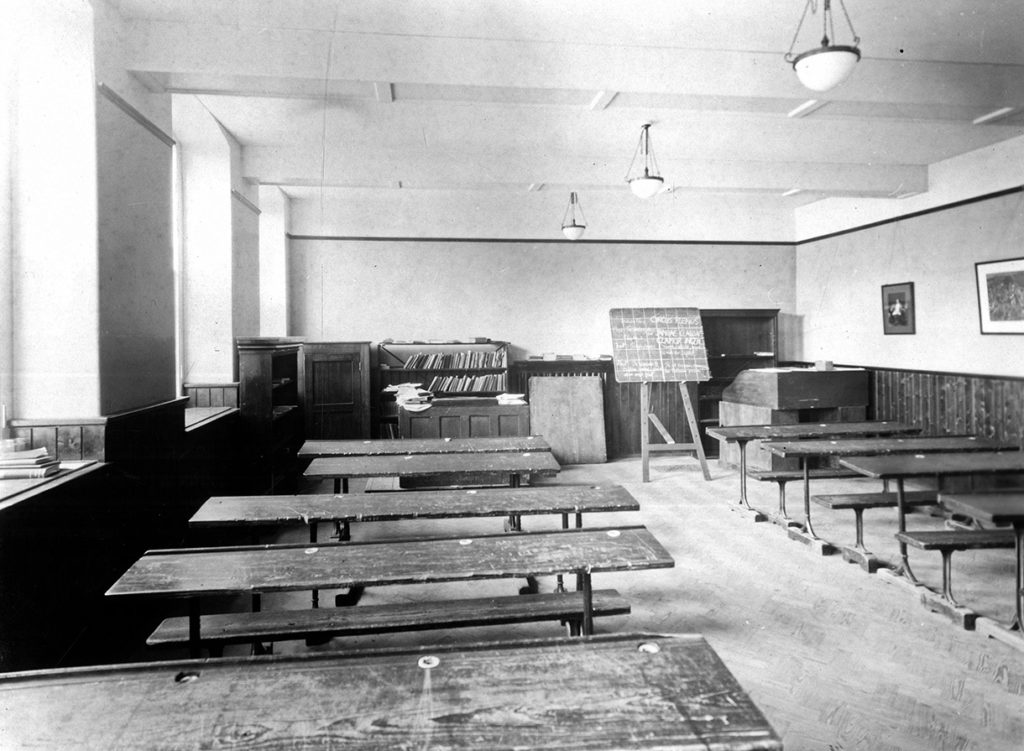

‘All teaching then was blackboard based, with none of the modern and interactive aids available today. So much more of a challenge for teachers to keep their pupils’ interest and attention!’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

‘In retrospect, apart from the blackboard, there were very few visual aids. It would depend on the personality and skills of the teacher.’

Thomas Collett-White (Picton 1950-55)

‘I think, for my generation, there was a menu of subjects that needed to be taught for the exam but there was little attempt to make learning interesting and applicable to life experience.’ Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953-57)

‘My memory is of a traditional teacher-centric style reinforced by a substantial “preparation” workload every evening. The atmosphere in the classroom was always positive and respectful. The learning environment was teacher-centric but we were encouraged to search the literature, be creative, and present our own ideas to be discussed.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘The ushers and their teaching methods varied enormously. Indeed, I never met a more idiosyncratic group of professionals before or since. Some were brilliant, and I consider it a great privilege of my life to have sat at their feet. Some infused their lessons with humour and fun whilst still delivering good, solid teaching; others achieved somewhat lesser results by what can only be described as a rule of terror.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

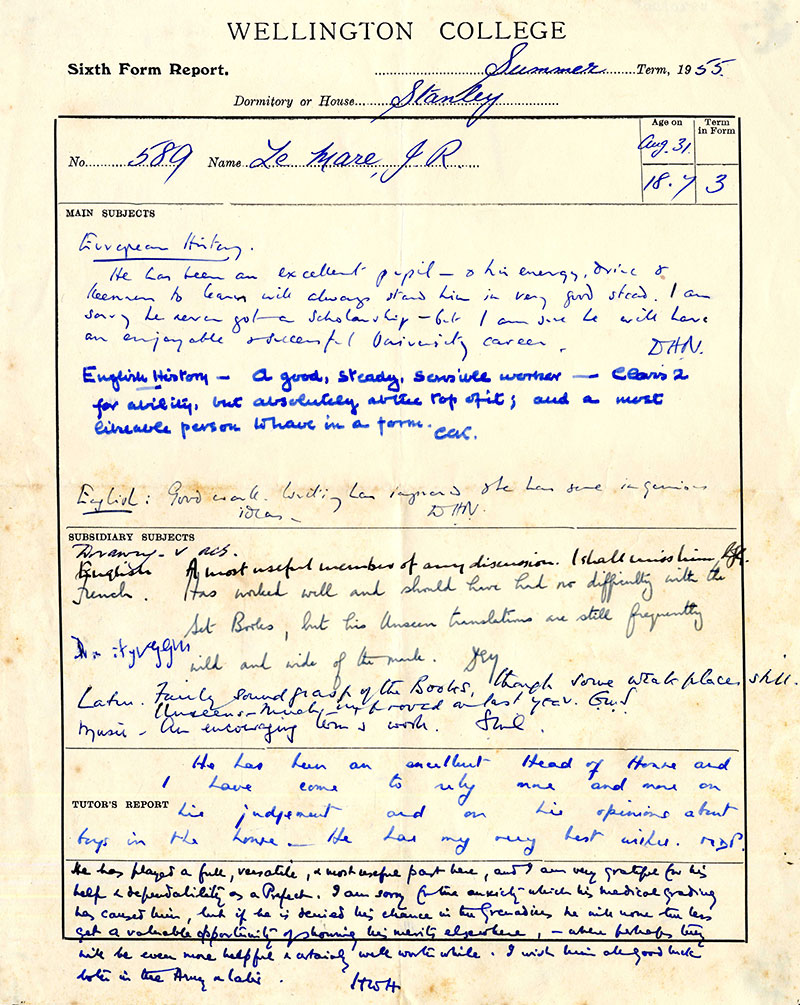

‘Challenging, but realistic. Given plenty of “prep” but facilities such as the library were excellent. We were quite diligent and did not fool around “much.”’ John Le Mare (Stanley 1950-55)

The War’s influence

Several respondents identified the Second World War as having an appreciable effect on their education. The War itself clearly impacted the availability of teachers:

‘The staff at Wellington during the War tended to be a curious mixture of persons exempted from military service for one reason or another.’ Peter Bell (Blücher 1943-48)

‘With young men away at the War, we were left with a worthy Second XI of staff too old or incapacitated to fight.’

Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

Some continued to feel this, even after the War:

‘For the average boy, the standard of teaching was below par. Wellington had not yet benefited from the infusion of younger teachers returning from war service. Many of the teaching staff were too old or infirm to be called up and continued to teach at the College and were still in situ in 1949.’ Henry Beverley (Anglesey 1949-53)

‘Those available for teaching included older men and those unfit for service. Some were very good, and I am sure others did their best, but today’s staff are in another category.’ Anonymous (1948-52)

‘In my day, they were a motley crew! The Common Room was still recovering from the War years when many of the best teachers were conscripted or killed.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

‘The school was picking itself up after the educational restraints and costly derelictions of a long war, including a low point when the master had been killed… Its image had also suffered from a series of local burglaries perpetrated by boys.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘Looking back, I think Wellington, and perhaps other public schools, were in a post-war time-warp. Some masters were good, but none inspirational, with the majority past their sell-by date and living in a pre-war or even Edwardian world.’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

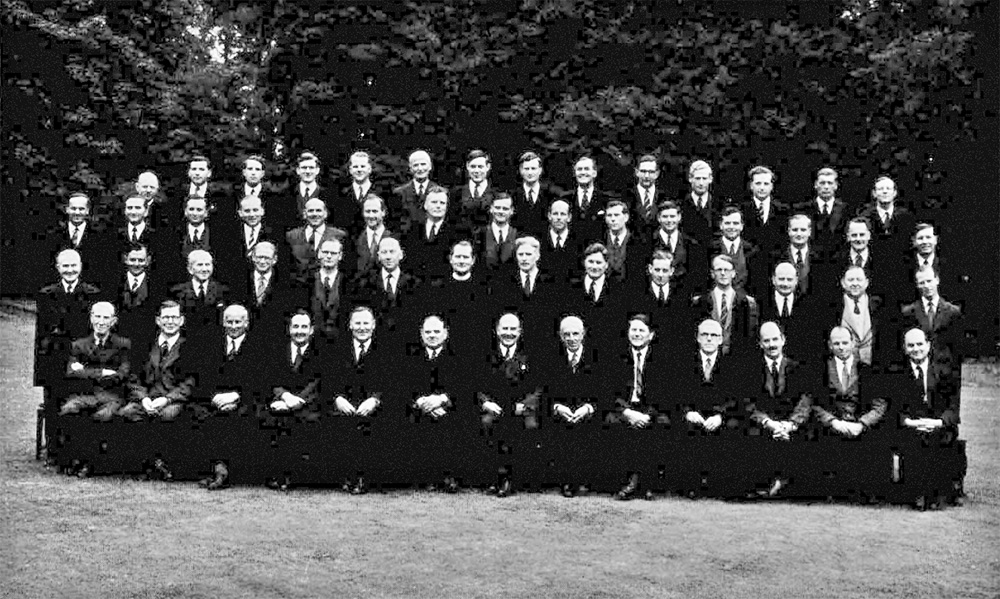

Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56) offers an effective analysis of the 1950s’ teaching staff:

‘Broadly, I would divide the staff into three groups. There were a few older men who were approaching retirement and had served in the First World War. Typical of these was Colonel Roy. There was a middle-aged group who had graduated in the 1920s and ‘30s and gone into teaching as a career. They were too old to serve in the Second World War and had continued teaching. An example was my tutor in the Picton in 1951, Rupert Horsley. The third group were younger, and many of these had seen active service and, as we shall see, bore the consequences of it.’

Many of these younger teachers were respected due to their War service:

‘Many of the staff in our day served during World War Two in the armed services. I don’t suppose any had been through any form of teacher training, but their experience of the world more than compensated.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

‘When I was there, nearly all the staff had served in the War, in most theatres – Burma, including Chindits, to North-West Europe and the Atlantic convoys. As far as I remember, they were all afforded some degree of respect.’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

And due to their effect on the school:

‘There returned from the War an increasing flow of young, energetic, and amusing teachers, some of whom had taught at Wellington before the War. They, with their interest in people, their management techniques honed in the services, and their sense of fun, were modernisers. Their impact was immediate: they brought breaths of fresh air, new brooms, and winds of change!’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

But some still suffered long-lasting effects from the War. The students’ response to this is movingly described in the passage below:

‘One distressing example involved my Physics master, a small man of gentle disposition. I have no idea what he had experienced but it must have been pretty terrible. In the 1950s, Britain had an advanced aircraft industry and was developing a lot of experimental aeroplanes. Being situated close to Farnborough, these would fly over Wellington very low, emitting sudden loud noises. When this happened, he would, quite involuntarily, hurl himself under the nearest bench for protection. This might happen two or three times a term. When it did happen, the poor man was terribly humiliated. Somehow, we boys recognised his great courage in continuing to teach and reacted kindly to him. The approach was: “Bad luck, Sir!” helping him to his feet. “It was just an aeroplane; take a minute to get your breath back. Now, you were just telling us about kinetic energy.” And on the class would go.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

Lives and careers

Career guidance in schools was in its infancy in the 1950s, with many respondents feeling that this was a particular area in which their Wellington education was lacking, or even misleading:

‘Very laid back. No real interest taken by tutors or staff as to where one might go in life.’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

‘I was asked if I wanted to go to university and, having just worked for my O Levels, foolishly said I did not – in consequence, I spent the next two years wasting time and my father’s money.’

John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘Mr Fergus Russell was said to believe that public schoolboys should not go to university, as a result of which I went straight into industry (where courses were prepared by Sheffield University and Polytech). Another boy, similarly dissuaded, subsequently became a professor in a US university.’ Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52)

‘Career planning was non-existent at Wellington when I left. The only career advice I received was from Marston, who asked what I wanted to do, then said, “Well, don’t expect to be a leader as you don’t have leadership qualities.” I was dumbfounded but determined to prove him wrong. He was wrong, because I ended up (with) a successful career in aviation as the director in charge of an airline business unit with 500 employees and (a) $100 million a year budget.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954-57)

In the absence of guidance, many boys simply followed their fathers’ careers:

‘It was never suggested that I should apply for university. Was there a Latin requirement which I did not achieve? There was no career counselling. With my military father, I imagine it was assumed I would march down to Sandhurst.’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

‘The choice of Classics to a large extent determined my future career, and I enjoyed them; but if I had my life again, I might well choose History or English Literature instead. In fact I hardly made a choice. It just seemed natural that I would follow in the footsteps of my father, and specialise in Classics.’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952-57)

Although those who had strong career plans of their own could be successful:

‘I declared a single-minded intent to go into the Navy, by Special Entry, which meant finishing in the General Sixth (known as the ‘Army’ Sixth not long before this). Scholars were, presumably, meant to get Oxbridge scholarships. By the time I left College, I was top of three sets. I gained an excellent result in the Navy, Army, and Air Force entrance examinations; the exam for special entry to Dartmouth.’ Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53)

‘My father died unexpectedly in 1955; and I remember, soon afterwards, consciously deciding I wanted to go to Oxford or Cambridge. To do so, I assumed I would need to win a scholarship to pay for the cost. I set myself that goal and subordinated other school activities to achieve it. That meant working very hard in both the term and school holidays and giving less time than most of my contemporaries to sport and other activities. Later, I (made) myself unpopular for this choice. And many of my school reports commented on my over-seriousness.’ Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

Some felt Wellington equally supported both pathways of the Army or universities:

‘In 1945 when I arrived, Wellington was very much an Army school with a strong accent on preparing boys to pass the Army exam. As I progressed up the school, this changed to preparing many of us for university entrance; definitely what I was aiming for.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘Wellington still performed an important role as a training ground for a career in the armed services. One of the sixth form groups, the General Side, had a curriculum which suited military entry. The other “Sides,” the Modern for language specialisation, the Science, the Maths, the History, and the Classical, directed studies towards university entry with A and S Level examinations. It should be said, however, that university choice at this period was focussed almost entirely on Oxbridge or the London colleges. “Red Brick” universities were seen as infra dig.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

Yet many still left in a state of mind beautifully summarised by Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54):

‘Presuming National Service and the university would save me from worrying about my future for five years, I left Wellington with only happy memories and cheerful self-confidence, and complete ignorance of what my time there had lacked.’