Music, Theatre and Art

Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948–1950) wrote ‘Looking at the present College Year Book, one is struck by how much emphasis there is on the Arts. In the late 1940s, there was virtually none.’ Nevertheless, a large number of our respondents had memories of music and drama at College.

Peter Rickards (Murray 1947–52) told us ‘We all participated in theatre and music. Dormitory and school plays and choral competitions were as constant a commitment as games and sports.’ For some this might be a walk-on part in a dormitory play, for others, strong involvement in the musical activities on offer.

Music teachers

Music played a part in the curriculum, but individual music lessons were extra-curricular, as were the various orchestras and choirs.

Several respondents felt that music had been one of the most important aspects of their lives at Wellington. Inevitably, music teachers had a strong influence on this, and were largely remembered fondly.

‘The teacher who stands out as a beacon in my memory was my piano teacher Mr Timberley. He was a rotund little man and a brilliant pianist, even with hands markedly smaller than my own. He had a varied method of teaching, sometimes playing through the repertoire of the next Subscription Concert, pointing out passages to look out for; sometimes getting me to play pieces while trying to distract me by asking questions, by jumping up and down and by pretending to slam the keyboard lid down on my hands. He was an excellent teacher and I loved him dearly – I still do.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946–51)

‘The person who was best was the assistant Music master, Mr Angus.’ Michael Moore (Lynedoch 1955–60)

‘Alan Angus was a young musician who taught the piano and helped out by learning to play the viola so as to join in the string quartet we formed. We played Haydn’s Emperor Quartet. Alan Angus went for bicycle rides on a tandem with his young wife. When the composer Gerald Finzi died, Alan Angus and I rode on his tandem to a nearby railway station and travelled to London by train, to attend the memorial service for him.’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952–57)

The teacher remembered more than any other was the Director of Music, Maurice Allen.

Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946–51) considered him ‘adequate but rather limited in his scope. For instance, once while we were chatting, he noticed a boy entering the Music School carrying a guitar case, and his greeting was “That’s not a proper instrument.” How wrong he was!’ For those who enjoyed classical music, though, Mr Allen was inspirational:

‘The person who had a lasting influence, and whom I often think about, was Maurice Allen. He was a wise, tolerant, and civilised teacher and the nearest among the teachers to being a friend despite the large gap in our ages. Michael Howard OM, who died last year, told me of the civilising influence that Maurice Allen brought to the school. Allen directed plays and Gilbert and Sullivan operas. I had the good fortune to win a music scholarship. I have a letter from Maurice Allen announcing this award and making clear that it was awarded on promise rather than performance. After a term or two with the sweet and kind Mr Timberley and then the diminutive Tommy Evans I graduated to Maurice Allen himself as teacher. He encouraged me to play Brahms, Beethoven, Grieg lyric pieces, Debussy (Girl with Flaxen Hair, The Sunken Cathedral). The stiffness of my hands and wrists drove him to melancholy, but he seemed to recognise that there was nothing to be done. Music extended beyond the piano and violin lessons into singing, where a whole world opened up through Vaughan Williams (Toward the Unknown Region), Stanford (The Revenge), even Edward German, Mozart’s Requiem, Brahms’ German Requiem, Bach’s Matthew Passion, and of course Gilbert and Sullivan.’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952–57)

‘It was impossible to escape the very remarkable Director of Music, Maurice Allen. In the face of all indications in my case to the contrary, he would not give up on the assumption that every boy must have some talent, either to sing or to play an instrument. He sat me in the second violins, largely clueless as to what was going on. He must, however, have inspired an appreciation of music in hundreds of young people, however poor their performances might have been, as he did for me.’ Peter Marshall (Stanley 1947–51)

‘Wellington was not a musical school in my day, but Maurice Allen, the Music Director, did amazing work under the circumstances of poor encouragement from above.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954–59)

‘Maurice Allen was my tutor, piano and singing teacher. He was a brilliant and gifted musician, quite inspirational, a bit of a hero of mine. He had a gift given to very few: he could sit in front of a full orchestral score of an opera and do a piano reduction at sight; the only other two people I know of who could do this were the composer Benjamin Britten, and the late Kenneth Mobbs. Thanks to Maurice Allen, I was able to pass A Level Music, notwithstanding having only three terms to do the necessary study.’ Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951–55)

‘I never played an instrument but the very inspiring Music master, Maurice Allen, taught musical appreciation in occasional classes, which has proved of lasting benefit.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949–54)

‘Thanks to my membership of the choir and to Maurice Allen, I acquired a lasting appreciation of classical music.’

George Nicholson (Hardinge 1949–54)

Music lessons

Some had memories of their individual music tuition. Two respondents, encouraged by their teachers, were able to get places in the National Youth Orchestra:

‘Our violin teacher was an itinerant, Jack McDougal, who came to College for one or two days each week. He was an excellent instrumentalist and a nice man, who crouched in the freezing rehearsal room with the gas fire turned up to maximum strength to reduce the shivering he suffered as a result of wartime malaria. He never got me to play a true staccato.’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952–57)

‘The next “moment of truth” was my decision to give up the piano. Expecting my father’s wrath – he was a good pianist himself – I was surprised when he asked what I intended to take up instead. Without thinking, I blurted out that I would play the horn. The first whiff of stale tobacco and old Brasso given off by the battered old school instrument captivated me and I have been a horn player ever since.’ Ross Mallock (Murray 1954–59)

But those with a more modest ambition also got something out of it:

‘I’d learnt the piano for a few terms at prep school … I started piano again at Wellington, under Maurice Allen. I told the Music Master that what I really wanted was to sit down casually at a piano and astound anyone listening with my playing. He advised me to choose a few pieces and he’d help me learn them by heart. I did manage this … after which I would get up and say “That’s all for today, folks!”’ William Shine (Hill 1956–60)

Orchestra

‘Every Monday evening, when others were doing prep, we had orchestral practice in the Music School. The orchestra consisted of all and any pupils who played an instrument, and some of the ushers and their wives. Jack Wort played violin or viola, I seem to remember. Mrs Potter was a fine pianist who performed a Mozart concerto at the Speech Day concert.’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952–57)

‘Music was my great consolation. The College orchestra practice every Monday evening under Maurice Allen’s baton was the high point of my week. Even my academic work began to improve.’

Ross Mallock (Murray 1954–59)

‘I particularly liked the clarinet which some jazz chaps played so well on the radio … but I never practised enough. I was put into the School Orchestra sometimes, and distinctly remember losing my place in the music, in which case I would blow out my cheeks and waggle my fingers in time with the other players. No one ever knew.’ William Shine (Hill 1956–60)

The Choirs

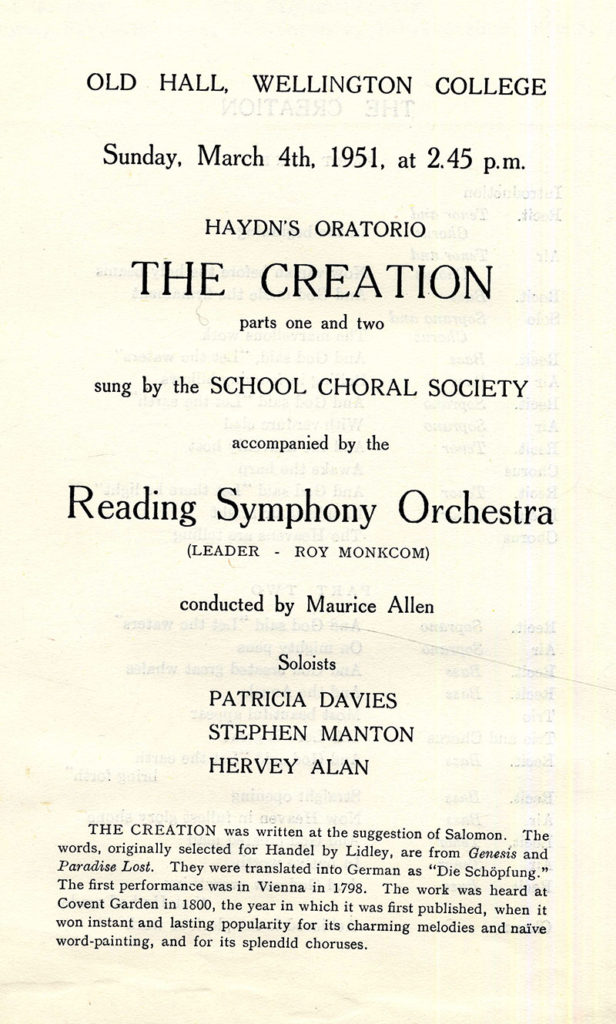

‘I never played an instrument, but was roped into College Choir, and thoroughly enjoyed singing in The Creation without ever learning to read music.’ Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947–51)

‘I joined the choral society as a bass at the age of 13 under the baton of the inspirational Maurice Allen; from my point of view it was a life enhancing experience and something that has stood me in extremely good stead for the rest of my life. I recall performances of Messiah, the Mozart Requiem, Towards the Unknown Region by Vaughan Williams and The Revenge by Stanford; lots of other works too!’ Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951–55)

‘I was Prefect of the Choir, of which I was a very keen member. With two others in the Small Choir, as a special treat, I was taken to a concert of The Dream of Gerontius; I broke the rules during this Reading visit by buying my first ever pint of beer in a pub (for one shilling and ninepence in old money, I recall!).’ Christopher Birt (Beresford 1955–60)

’I was delighted to be picked as a treble in Tommy Evans’ Small Choir, which introduced me to choral singing of an altogether higher standard. Looking back, I’m sure that this was the start of my musical education. Even now I can’t listen to the St Matthew Passion without a nervous jolt. The choir performed it during my second year and Tommy Evans approached me on the morning of the performance with the unwelcome news that the treble briefed to sing a short solo had gone down with flu. I was so shattered to be given the job that I never mentioned it to anyone – even my parents, who were in the audience that evening.’ Ross Mallock (Murray 1954–59)

‘A memory that has lasted is that of being auditioned for the choir by Maurice Allen. I had just got my mouth open when he said, “That’s enough – next!” So the world missed another Pavarotti.’

Allen Molesworth (Blücher 1945–48)

‘I took care not to be involved in any choirs.’ Rufus Heald (Stanley 1939–42)

Listening to records

Listening to great music was an important part of the musical journey for many, and the Music School afforded an opportunity for this:

‘Music was the best part of my life at Wellington and is most strongly associated with a particular place: the gramophone room on the first floor of the Music School. Here, as sixth formers, my friend and I spent most of our free hours exploring the repertory, Sibelius symphonies, Elgar violin concerto, Vaughan Williams’ Job: A Masque for Dancing. The years at Wellington were the foundation of my musical knowledge.’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952–57)

‘I used to sneak into the Music School and listen to music – a wind up record player with fibre needles and a great enormous horn. I was very keen on the Beethoven symphonies and used to follow in the scores.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945–50)

‘I made use of the Music School’s record library (mainly 78 rpm in those days), and I recall the wonder of playing bits of Die Meistersinger on these records.’ Christopher Birt (Beresford 1955–60)

Some also remembered music heard in their dormitory:

‘There was a gramophone in the Anglesey, with a good supply of vinyl records, including Dvorak’s New World Symphony, Liszt’s Les Preludes, Phil Harris’ Woodman Spare that Tree, and the Ink Spots’ I Like Coffee, I Like Tea.’ Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947–51)

‘Thanks to a dormitory companion who seemed to have a mission to teach classical music, I was introduced to Beethoven. I am eternally grateful to him.’ Michael Mathew (Murray 1956–60)

Concerts

Hearing live music at a concert could be even more inspirational:

‘An unforgettable memory was Courtney Kenny as soloist in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4, at the Summer 1950 College Concert. (He later had an impressive musical career.)’ Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947–51)

‘I went to all the Subscription Concerts given by very eminent musicians. The Dolmetsch family gave one of these concerts. As a result of hearing them, I took up the recorder, subsequently taking flute lessons and playing in the school orchestra.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945–50)

‘I am afraid I was very much a square! I liked only classical music and was introduced to this by attendance at the Subscription Concerts held in Old Hall.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949–54)

‘The Wellington Subscription Concerts I always attended, and they introduced me to pieces of music I have loved ever since.’

Christopher Birt (Beresford 1955–60)

And of course, taking part was very memorable:

‘The Concert was the traditional end piece or climax of Speech Day, ending with a rousing rendition of the College Song, “Praise to the egregious Duke”, we sang. One year Royalton-Kisch, a wealthy music lover who conducted occasional concerts by the big London orchestras, took the baton from Maurice Allen and conducted us in the Radetsky March of Strauss. In other years I was the soloist in The Lark Ascending, and in the first movement of the Mozart Concerto in A major. In another John Le Mare and I played the first movement of Fauré’s Dolly Suite.’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952–57)

The Sing Song Society

Others took part in concerts which were far less high-brow, but equally enjoyable:

‘The singing led to membership of the Combermere Cads, our Sing Song Society which entertained other dormitories and visited local pensioners clubs. We sang patter songs, rounds, madrigals and bowdlerised rugger songs. Even now I can brighten your evening by singing The King of Kathusalem and much else. Beware!’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944–48)

‘I also performed with the Sing Song Society, run by James Wort, giving concerts in old people’s clubs around local towns and villages with ballads and shanties, where I performed the occasional comic monologue, copied from ancient gramophone recordings in the house of an aunt in Wales.’

Alan Munro (Talbot 1948–53)

On and off stage

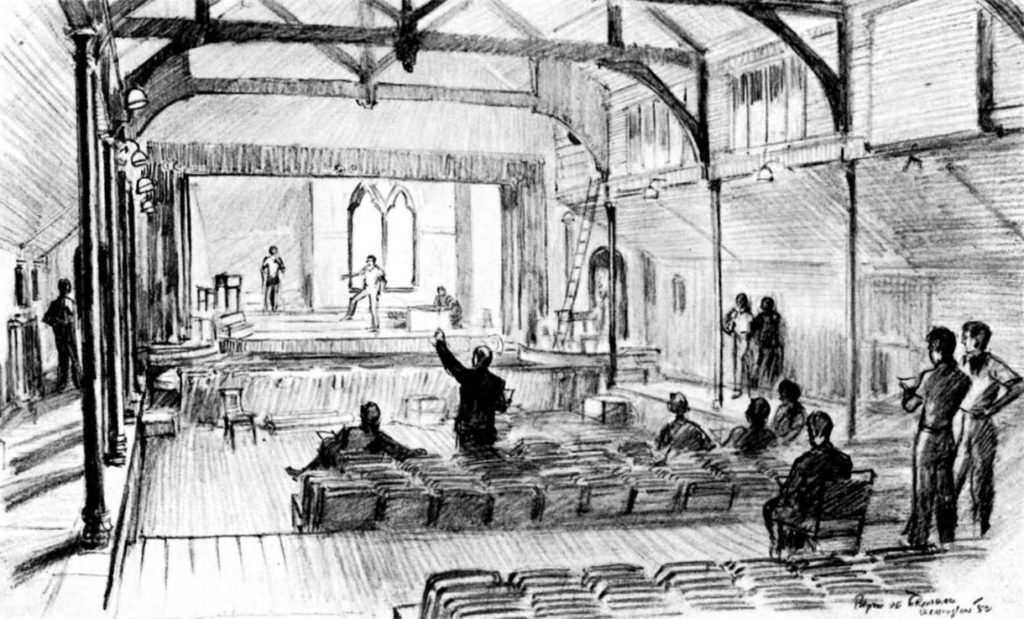

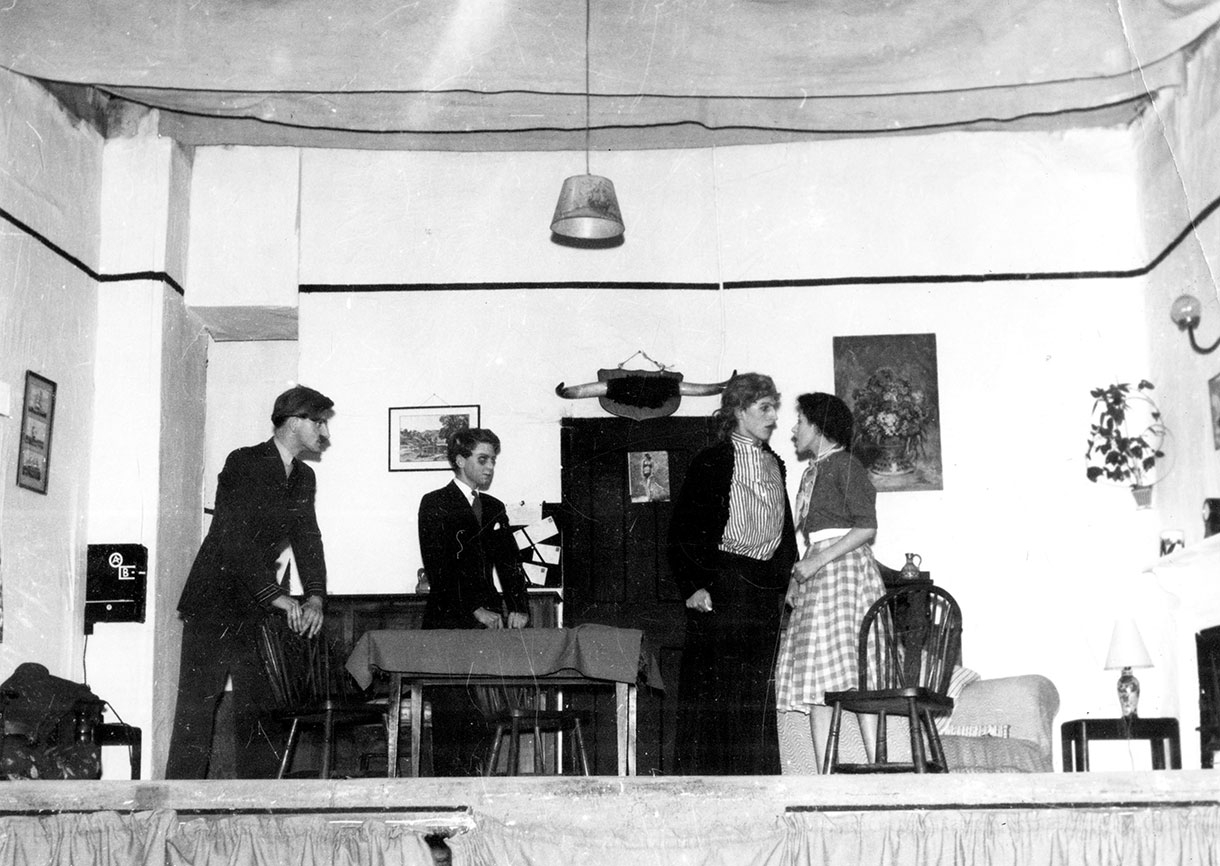

The dormitory play was a Wellington institution in the 1940s and 1950s, alongside larger school productions and occasional visits from external groups. Some remembered their involvement being mainly behind the scenes:

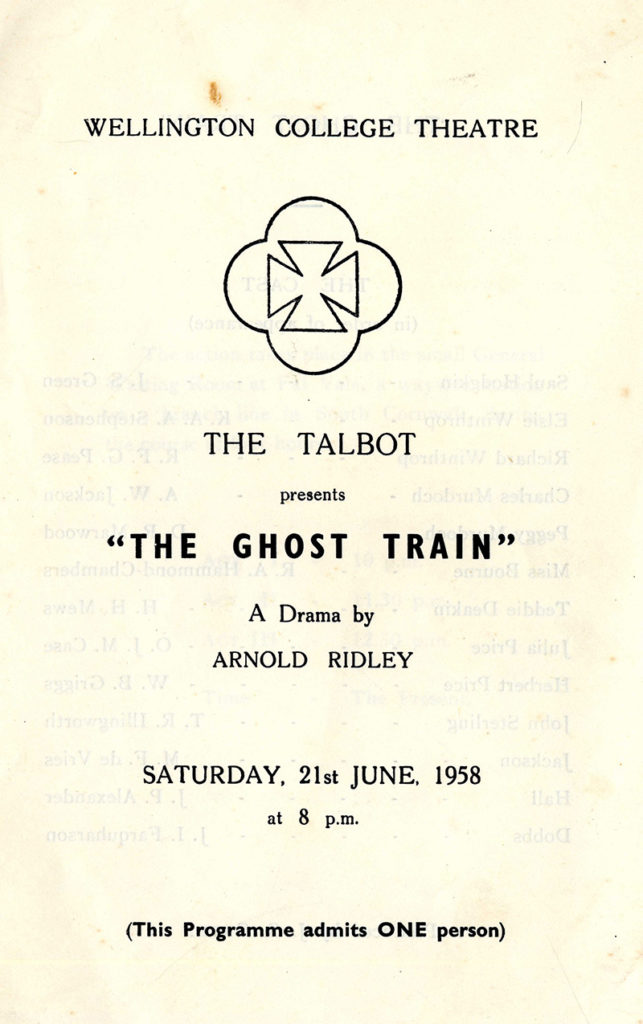

‘The Talbot had a very close association with the then theatre which was built in the old swimming pool. We had a monopoly doing the lighting and the makeup, taught by James Wort.’ Anonymous

‘Talbot ran the theatrical makeup – Peter Snow of television fame’s first makeup was, possibly, applied by me when he was starring in a production – and, in my last year, I directed and acted in The Ghost Train which the House put on for the school.’

John Green (Talbot 1954–58)

‘During my last years the old indoor swimming pool was converted into a theatre, very much under the direction of Maurice Allen. I took part in two Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. It had a modern lighting system and I learned all about the lighting board.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945–50)

‘During my time at Wellington, the tradition of the annual dormitory play, performed on an improvised stage rigged up at the end of the dormitory passage, gave way to far more professional productions performed in Old Hall. I think that this rise in the standard was largely due to John Lowe, a very talented intellectual in the Hardinge. The first play that he directed was Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, in which I played a minor part. Subsequently I designed and painted the sets for both Dormitory and College productions.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944–48)

This production of Doctor Faustus was also remembered by Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946–51):

‘The Hardinge plays had a good reputation and were much sought after in the barter exchange for tickets. The most memorable to me were the last, Charlie’s Aunt in which I took the main part in spite of being some six inches taller than called for, and the first, Dr Faustus, a massive undertaking, especially for the lead part taken by John Lowe, our Head of Dormitory. It was all the more remarkable for being a complete break from the then usual revue style of production and was considered so notable that the Master asked for (ordered) a repeat performance the following day. No such request followed our Charlie’s Aunt presentation.’

In the audience

‘There was a performance of The Ghost Train by the Talbot. In this, a spinning array of light bulbs off stage simulated a train passing through the station at night. This was most realistic and greeted by spontaneous applause. Another highlight was a performance of Ruddigore in which members of the teaching staff took lead roles.’ Alan Saunders (Orange 1957–60)

‘Another highlight was the visit of a Canadian high school drama group who put on a performance of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Nothing made the impact of that theatre production. With just a few hard backed chairs as props, the life of a small town was enchanted into existence by good acting. It corresponded with my ideal of theatre, as expressed by Peter Brook in his book The Empty Space and it instilled the seed of a lifelong love of the theatre.’ Richard Harries (Hill 1949–54)

On stage

Some stage appearances may have been little more than ‘bit parts’, but they were never forgotten by the actors:

‘I played a Deadly Sin in Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, a Princess of France in Love’s Labour’s Lost and produced a Victorian rustic melodrama called Speed the Plough.’

Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943–48)

‘Mr Wort’s skill lay in seeking out some accomplishment in each boy on which he could build self-confidence and achievement. In the case of shy young Stacpoole, PMR 404, it took the form of getting me on the stage. Starting from kicking away in the chorus line of our Dormitory annual song and sketch revue Sailing Away on the Crest of the Wave, I graduated to playing an ingenue smoking a pastel-coloured Balkan Sobranie cigarette and then to an asthmatic Cockney petty thief but no further. Mercifully.’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944–48)

‘I took part in my last term in the House play – we performed The Hasty Heart, which had then recently been made into a film with Richard Todd, THE current male heart-throb. I don’t remember that we really knew what the play was about … I cannot remember any of my lines other than that I had to be able to recite the sequence of the Books of the Old Testament, and, what’s more, I can still get halfway through!’ Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948–1950)

‘I acted in our Dormitory play, Worm’s Eye View, produced by Charles Ritchie, a great admirer of Tony Hancock. I played a council worker in charge of sewers. One line was meant to make the audience laugh: “Don’t laugh at my job. It’s important, y’know – there’s a lot in drains!” Maybe some people laughed!’ William Shine (Hill 1956–60)

‘I was involved into two productions: a House play, The Ghost Train, and a College production of St Joan in which I was a suitably weak Dauphin. In the House play I played a female role, as I was in my first year, and this called for me to smoke a cigarette, something of which I had no experience. To give a convincing performance as a casual smoker, I had lessons with an authorised adult – I always intended to use this in my defence if caught smoking later in my career at College! Later in the Classical Sixth I played a role in a riotous version of Aristophanes’ The Clouds which involved descending from the “flies” in a laundry basket – probably best forgotten!’ Adrian Stephenson (Talbot 1957–61)

Theatrical difficulties

Some OWs had rather traumatic experiences of acting:

‘In 1950 I took the lead part in the Anglesey production of R C Sherriff’s Journey’s End, resulting in my being given the lead in the 1951 College “Gravediggers’” production of Thunder Rock, about an American lighthouse-keeper who has vividly realistic hallucinations about the passengers and crew of ship bringing European immigrants to America, who had all drowned when the vessel foundered and sank nearby some sixty years before. I found this a very unnerving part and began to feel as if I too was being taken over. I never acted again after that.’ Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947–51)

‘Early on I took the female lead in a production of Nothing but the Truth, rather well I gather. But my Tutor wrote that it had gone to my head and resulted in poor work. In fact the cause of this was rather different. Playing the female lead brought about a fair amount of unkind teasing.’ Richard Harries (Hill 1949–54)

‘The only time I was ever asked to act in a play was in Hamlet (I think). I was given a minute one-line part as some sort of herald. I came on stage to announce the arrival of someone much more important and halfway through my voice broke back as a treble and brought the house down. I must have been about sixteen as my voice broke very late.’ Anonymous

Fortunately for most, their mishaps were merely humorous:

‘My only onstage appearance was as a cheese-grater in Aristophanes’ Wasps. I got it into my head to use some old sheets of corrugated iron into which I would hammer holes. I was given time off from classes to tackle this task. It proved utterly futile, and I resorted to painting the holes. Even then it was rather a bad idea as I could hardly move and made a fearful clattering noise as I prepared for entry.’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951–56)

‘In Hamlet, I played Fortinbras, the Norwegian king. All my lines had been cut save for the final lines of the play when Fortinbras comes to Elsinore … I also had a backstage role as the stage manager, a task I fulfilled in full acting dress, including my steel breastplate and makeup. The two performance nights were extremely hot, and I was soon shedding sweat copiously onto my armour as I performed the various physical tasks the stage manager has to undertake. Every time a large bead of sweat fell from my chin, there was a soft “plop” as it hit the breastplate. By the time my entrance on stage was due, the plops had become a constant stream so when I delivered my opening line “Where is this sight?” it was to the accompaniment of a series of plops. Horatio, you may recall, answers Fortinbras “What is it you would seek? If aught of woe or wonder, cease your search”; the biggest wonder was the king-designate of Denmark with sweat streaming down his front. Still, the theatre critic described my performance as “impressive” but what he was referring to, I cannot say.’ Richard Merritt (Picton 1954–59)

A sense of pride

Some students who took important roles, either acting or producing, clearly enjoyed themselves and felt a great sense of achievement:

‘The theatre was an important part of my life at Wellington. I produced a House play, which turned out to be a riotous staging of the then West End hit, Reluctant Heroes, receiving much encouragement from Tutor James Wort. And with a young German boy who was attached to the Modern Languages Sixth Form at the time, the two of us produced Kleist’s Der Zerbrochene Krug, affording us and the small but keen audience it attracted much hilarity. The German, Frank Beckmann, became perhaps my closest friend throughout life.’ Neil Munro (Talbot 1952–56)

‘I was very interested in acting and played in several plays, to such an extent that I had to seriously think about whether to become an actor.’

Hardy Stroud (Combermere 1950–55)

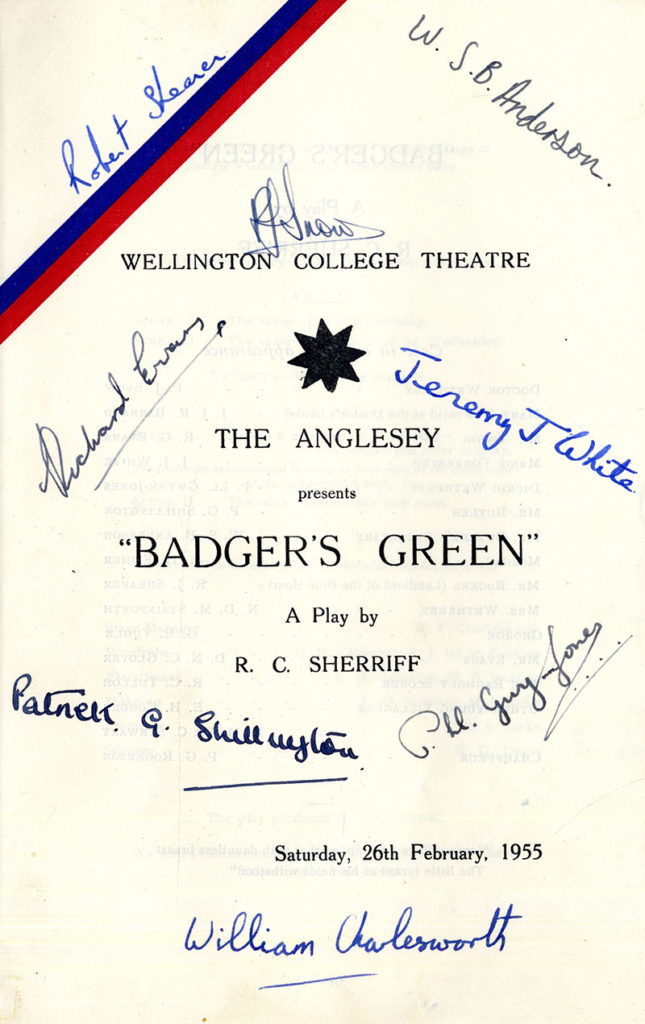

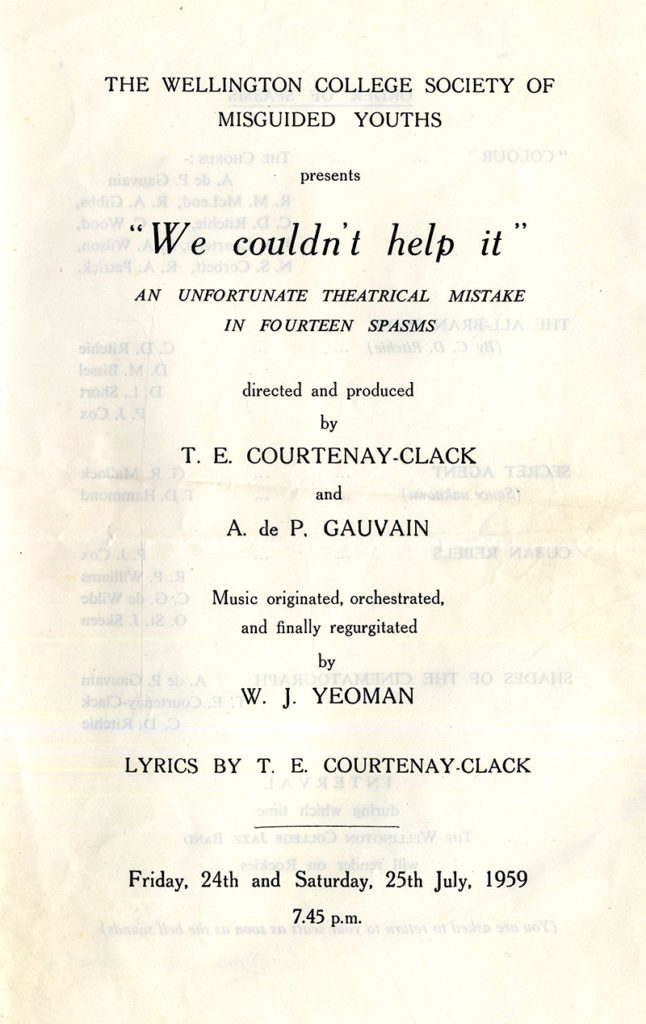

’At the end of my last Summer Term, I produced and wrote a College revue called We Couldn’t Help It with Anthony Gauvain. It was a big hit, requiring a third performance. As far as I know, this was the first theatrical production open to all talents in College who wanted to join in.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954–59)

But one of Thomas’ plans was a step too far:

‘During my last term I received an invitation to tea from my old nanny who was then Senior Matron at a girls’ school in Camberley. My nanny had arranged for the head girl, Fiona McKenzie to join us for tea. Fiona was charming and as it turned out, a theatre fan. An old notion of mine gelled and we eagerly discussed the possibility of getting together to do joint productions where actual girls played the female roles and actual boys played the men. I had barely arrived back at College when I was summoned to the Master’s office. Mr Stainforth was unsmiling. He had received a phone call from the Headmistress of the Grove School, a terrifying, ninety-year-old Victorian old bird who had caught wind of our plot and wanted it squashed at once. Stainforth told me that if he ever heard any more about this, I would be expelled.’

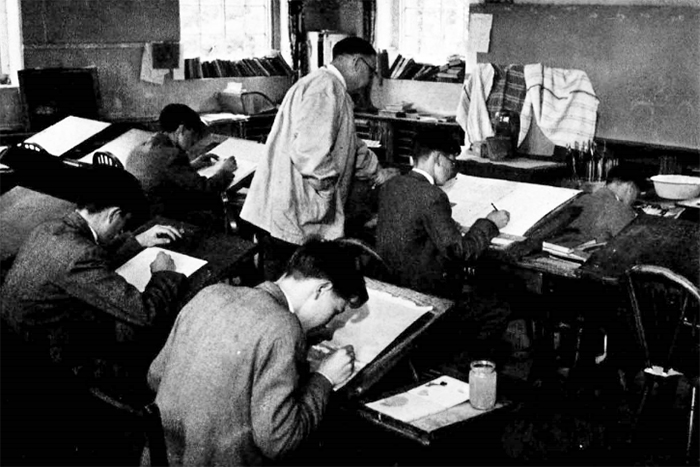

The Art School

Lastly, a few OWs recounted that their favourite times at College had been in the Art School:

‘The subject I enjoyed most was Art under the guidance of “Porky” Eccott, a very fine Slade-trained artist who used to draw the pictures for the French Common Entrance exams for many years.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952–55)

‘Art was taught by Mr Eccott who was a first-rate Art teacher … As far as I remember, I won all the Art prizes for which I was eligible (Junior and Senior Frew for example). I have good memories of Mr Eccott.’ Anonymous

‘I enjoyed half-holiday sessions in the metal workshop. Both this and the Art School provided me with lasting skills which I still use today, giving me untold satisfaction.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944–48)

‘The Art School was always open at weekends, thanks to two excellent Directors of Art: Arthur Eccott, who drew the pictures for the French paper in Common Entrance (for whom I occasionally modelled), and David Lindley, with whom I am still in touch over sixty years later. Wellington was certainly not a Philistine school in my time there. I designed and painted a few stage sets for the theatre. I was really happy in the Art School.’

Christopher Miers (Beresford 1955–59)