Discipline and Punishments

Discipline in the 1940s and 50s at Wellington was strong, with punishment usually swift and unambiguous. Nevertheless, we may have been wrong to lay so much emphasis on corporal punishment during the framing of our questionnaire; perhaps this resulted in skewing the responses towards something which was only one aspect of a larger disciplinary system.

NOTE: This page records practices and attitudes at Wellington in the 1940s and 1950s. Such practices and attitudes are outdated and in no way condoned by Wellington College today. They are included as part of our commitment to recording our history as faithfully as possible.

Non-corporal punishment

Some non-corporal methods of punishment are described in other parts of the ‘Decades’ section. For example, Biology teacher Mr Lewis’ notorious ‘Big Stuff,’ a laborious line-writing exercise, and ‘Coventry,’ a tortuous procedure which entailed the whole class sitting absolutely still.

Sanctions such as these caused more fear and resentment than beatings, perhaps because they lasted longer or because of their apparent pointlessness. John Thorneycroft (Benson 1953-58) recalls another such practice:

‘One particular nasty punishment in the Benson for a serious breach of house rules was to report to a Prefect every five minutes between 7.00am and 7.30am wearing alternately ordinary clothes and then “change” (sports) clothes. Quite tiring!’

Some recalled other forms of punishment:

‘Petty infringement of dormitory rules resulted in having to write these out a number of times. I recall one offender writing out the full rules on a postage stamp.’ William Field (Lynedoch 1952-56)

‘Other common punishments included “impos” [impositions] where you were ordered to handwrite something incredibly boring, like fourteen Shakespeare sonnets.’ Anonymous

‘I remember weeding the Combermere Quad as a punishment because I had walked on the grass!’

Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941-45)

‘… having to run up Finchampstead Ridges and take a rubbing of the brass sundial there! There was a back route to the Ridges, however, which passed the local nudist camp, called “The Heritage!”’ Michael Trevor-Barnston (Anglesey 1957-60)

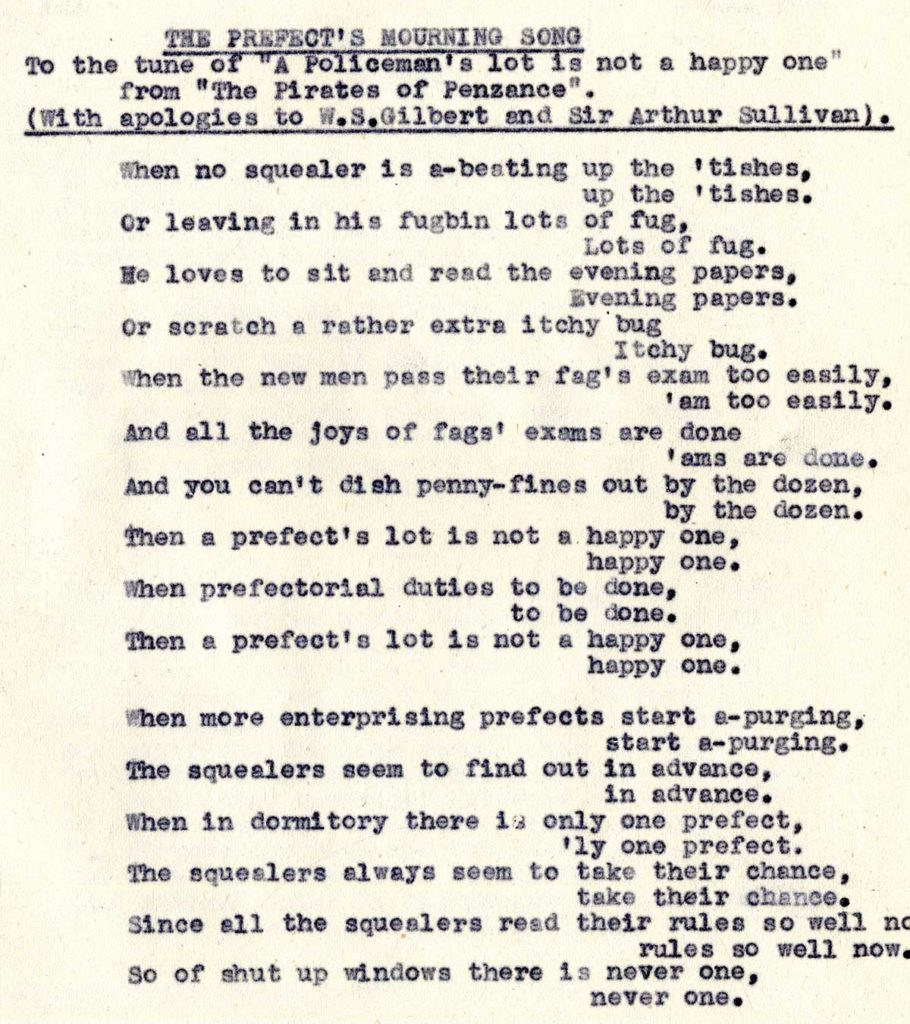

‘Punishments were for the most part notional, such as brief detention, the copying of “lines,” or cleaning and weeding tasks around the House. In the Talbot there was a system which involved “penny fines.” For a minor misdemeanour, you would be fined one (old) penny, which would go to House Funds.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

This system of penny fines appears universal, as it was mentioned by many.

The fines were innocuous in themselves, but added up to have more serious consequences:

‘Four fines in a week and you were tanned [beaten]. The first week at Upcott was forgiven, but, sure as shooting, I got four fines the second week. I’m not sure how the Prefects engineered it, but they kept finding my towel in the bathroom.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

‘I think I had two canings… The offence, five fines in a month for things like leaving your jam jar on the windowsill outside the dining room or leaving an article of sports clothing on the changing room floor. I still say I was set up on the changing room fines.’ John Armstrong-MacDonnell (Talbot 1952-56)

Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53) was of the opinion that ‘being tanned for too many “black marks” did encourage you to do better, or become craftier in the future.’

Levels of punishment

Fines were imposed for the most minor offences, particularly within the House or Dormitory, but many misdemeanours incurred the prospect of a beating. The system’s ‘hierarchy’ is explained by Richard Craven (Hill 1950-54):

‘I recall there were three levels: Headmaster’s or College beating, Tutor’s beating and Prefect’s beating. The first were few and far between, in fact I can only remember about two during my time. They were for the most serious offences, so knowledge of them went around the school like wildfire and further misdemeanours of similar severity would mean expulsion. These were carried out by either the Master or his deputy, Mr Meikle. Rumour had it that Mr Meikle would draw a chalk line across the offender’s backside for accuracy, hence his nickname, “Chalkie.”

‘Prefect beatings could only be administered by the Head of House/Dormitory and then only with the Tutor’s knowledge and by members of the Upper Ten. College beatings took place in the Master’s study, House Tutors in the Tutor’s study, Form Tutors’ in the classroom, College Prefects’ in the Upper Ten room, and Head of House, in the case of the Hill at least, in the Dormitory bathroom.’

Only one respondent, Rodney Fletcher (Combermere 1949-53), recalled being beaten by the Master, merely commenting that ‘He had a poor aim.’ Several, however, were beaten by teachers, for crimes which were more classroom-based: rubbing a memo off a blackboard, being very late for a lesson, carving your name on a desk, or being disruptive in class. House Tutors also beat those discovered off school grounds without permission. Perhaps most baffling to today’s mind, some teachers also beat boys for not doing prep, handing in poor work, or being bottom of the class. Even at the time, some questioned the point of this:

‘I really don’t think being beaten for bad French results made me any better at French.’

Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53)

‘The first beating I had was from my Biology teacher, Mr Lewis. I had failed to grasp some arcane and completely useless principle of biology. What thought process he went through to decide that a beating would help me grasp this incomprehensible biological principle is hard to imagine.’ Richard Wellesley (Benson 1948-53)

Two OWs sent in stories of how they avoided, or could have avoided, beatings from teachers:

‘My Tutor Mark Baker heard me whistling on the way to prayers in the evening. He invited me to come to his study after prayers where he said he was going to beat me. At the time I was playing number eight for the Wellington First XV and I certainly was not going to be beaten by him or anyone. I told him that I refused to be beaten and thank goodness for him and probably me, he dropped the case.’ Ian Nason (Orange 1950-54)

‘I was beaten by Charley Kuper for failing to “tick” him when we passed each other in the Quad. I decided to become much enraged by this, and, for a while, refused to look him in the eye or smile during our History lessons. Eventually he called me aside after class and asked me what was wrong. I told him that I had a moral objection to beatings. To my surprise, he replied that he would never have inflicted it had he been aware of my principled viewpoint. I felt an utter hypocrite, as in reality I never had any moral objection to the practice, which was of course universal at the time.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

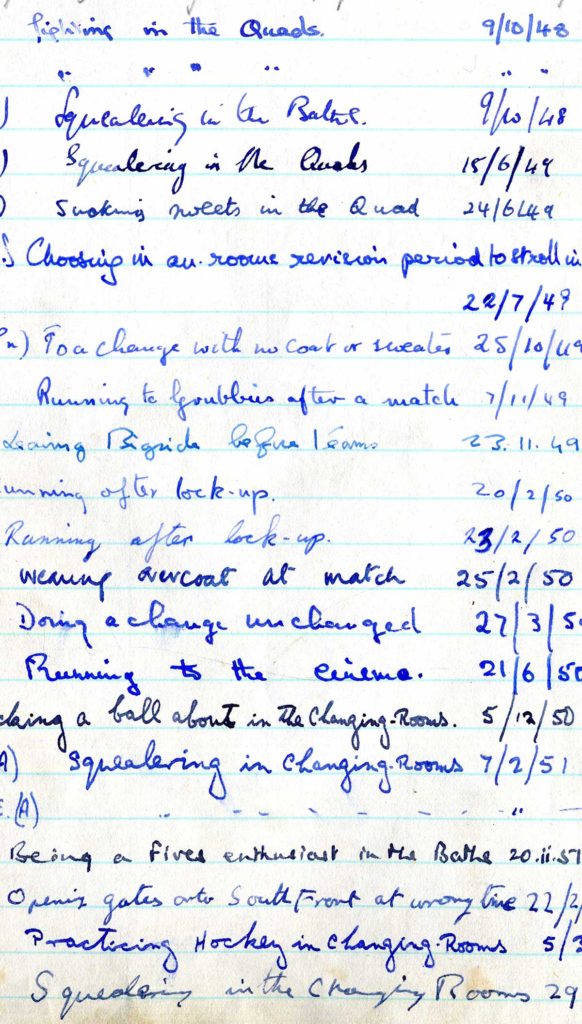

Most beatings, therefore, were administered by either Dormitory or College Prefects, or by the Head of House. Some were for important matters: three who were at College during the War years recall being beaten for failing to blackout their windows properly, and incidents of smoking (mentioned by very few) or bullying would still be treated seriously today.

However, many beatings were for offences we might now consider trivial.

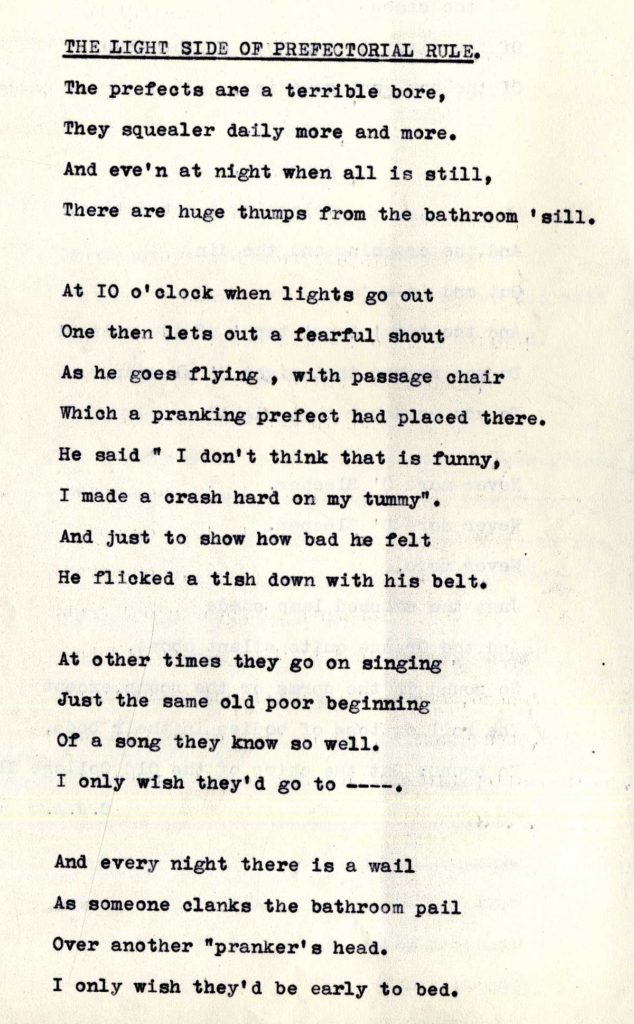

Examples given by respondents include running or eating where not permitted; walking on the grass in the Quad or cutting across the corner of ‘Turf’; talking, reading, or listening to the radio after ‘lights out’; contravening regulations regarding dress; or any behaviour that could be lumped under the term ‘squealering.’ One of the more unusual crimes was that confessed by Randal Stewart (Anglesey 1953-56):

‘I was beaten once by my Tutor and twice by Prefects. Another boy and I had ruined one of the Prefects’ saucepans trying to melt the lead out of spent .303 rounds, which we dug out of the old 500-yard range. The other boy was expelled the following term for taking lead from the College roof – we were making musket balls.’

It is difficult to say how frequent beatings were. A handful of respondents claimed they had never been beaten. Most seem to have experienced it between one and three times in their school careers; a hardy minority, more. Most could remember what their crimes had been, but a sizable group could not; suggesting that beating was not always the deterrent it was meant to be.

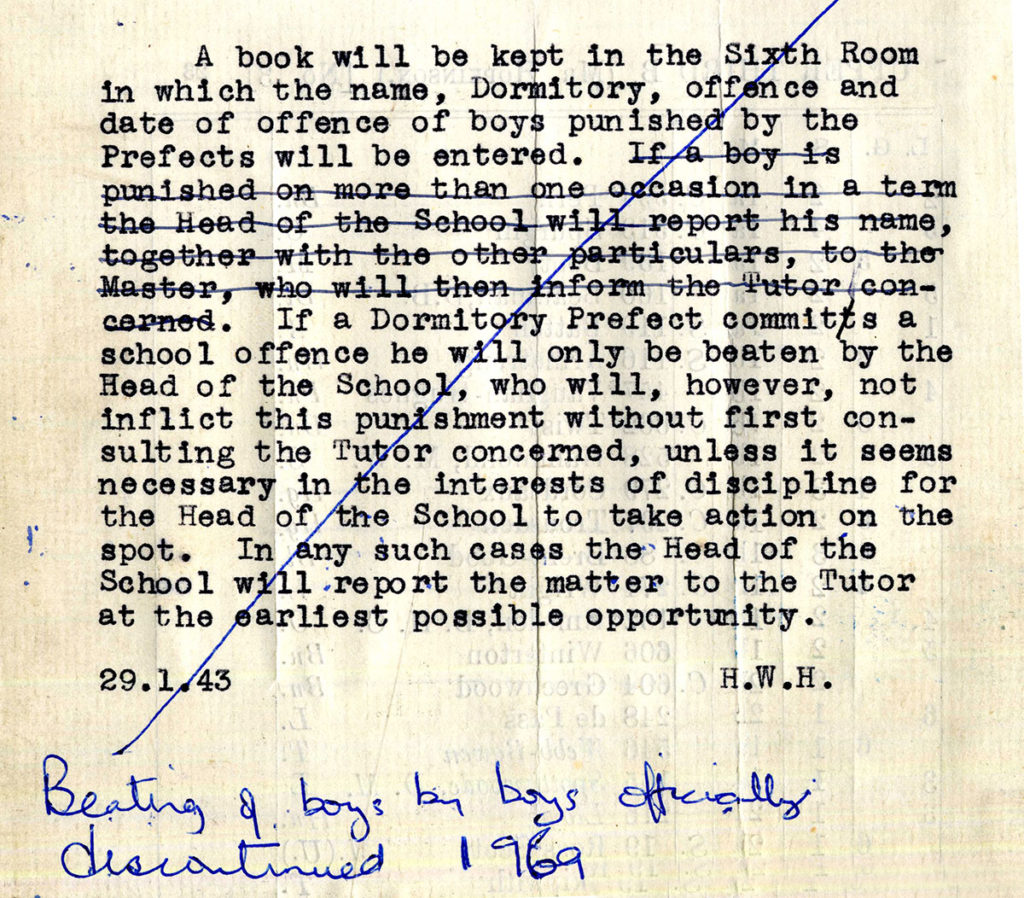

There were checks and balances in the system, intended to prevent the Prefects from abusing their power.

Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58) wrote that ‘Prefects had to ask Tutors for permission to beat boys,’ while Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53) believed that ‘in the Talbot, it had to be authorised by the Head of House.’ Perhaps this was the case for House or Dormitory Prefects; however, College Prefects only had to seek permission after the event.

Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953-58) states, ‘Every time, the Prefect had to write to the Master saying, “I today had occasion to beat X for …,”’ confirmed by Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56): ‘A College Prefect could beat a boy from any house/dormitory and just inform the boy’s House Tutor afterwards!’

The system meant that most beatings by Prefects were administered to significantly younger boys, but one respondent recalled an exception:

‘I was caned in my fourth year, when I must have been close to seventeen, for failing to respect a no-go area on Rockies. I was several inches taller than the Prefect!’ Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60)

What was it like?

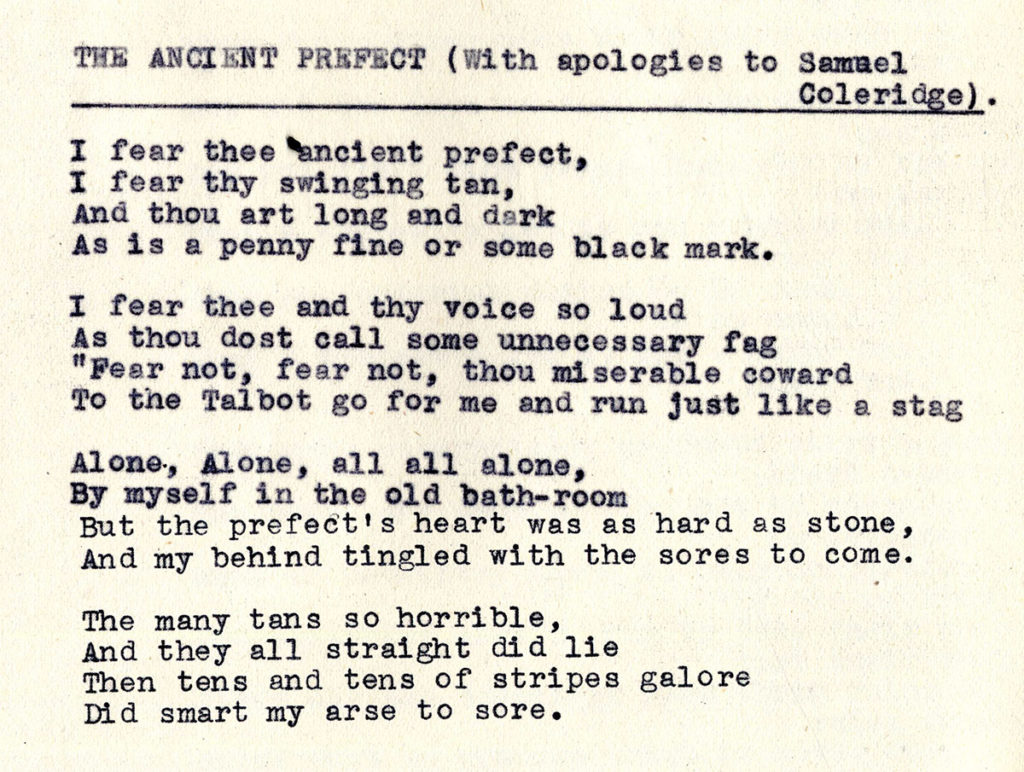

Beatings were something of a ceremony, or in the words of Richard Harries (Hill 1949-54): ‘A terrifying piece of theatre.’ The ritual became well-known to everyone:

‘You were beaten, I think on Friday, at 10pm, in the Tower. Six strikes usually, pyjamas only, the Head of House beat you. He was not allowed to raise the cane above his shoulder height.’ Michael Crumplin (Orange 1956-60)

‘Bit of a ritual. After bedtime, there would be a knock on your door and a voice would say, “The Head of Dormitory would like to see you in the bathroom. Bring a chair.” Bloody frightening!’ William Shine (Hill 1956-60)

‘Beatings were a ritual where the anticipation was almost worse than the actual punishment. They would take place immediately after lights out when the victim’s name would be called, for the whole dormitory to hear, and the unfortunate boy would shuffle down to the scullery on the floor below. They would wear pyjamas only and any attempt to insert newspapers or other paddings would be recognised immediately and result in extra strokes. The beating was administered bending over the back of a chair and clasping the bottom rail.’ Anonymous

‘The hard part was having to endure the wait between the notification of the punishment and the execution, which might be an entire day.’

Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60)

‘One of the rituals in the Hardinge was that, after every lunch, all boys had to brush their teeth and report to the duty Prefect clutching their toothbrush to be ticked off on the attendance sheet. There was one chilling exception to this: the passing down the table from boy to boy at the end of lunch, the dreaded message, “NO TEETH!” This signalled that there was to be a beating in the bathroom. Rather than brush their teeth, all boys slunk silently to their rooms and waited nervously to hear the footsteps of the Prefect going to the room of the victim to tell him the Head of Dormitory wished to see him in the bathroom. Then the unwilling footsteps of the miscreant down the corridor, the four interminably spaced cracks of the tan followed by the rather faster steps back to poor fellow’s room.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

Jock Brazier (Hill 1941-45) remembered: ‘Having to go to the steward to collect a cane which you handed to your Head of Dormitory, and you were beaten during second prep.’

As for the actual experience, an anonymous OW wrote that ‘The most terrifying part of being beaten was the swishing noise right by your ear which you heard about half a second prior to the “whack” sound when his cane bit into your bottom amid a brief, almost unbearable, stinging pain at that moment. The number of swish-whacks delivered on my bottom varied according to their contended magnitude of my wrongdoing. The majority of my beatings comprised six swish-whacks, that being the maximum number either a College Prefect or usher was ever allowed to give any of us.’

Most recipients did not comment on the level of pain inflicted, although one wrote that ‘It was agony,’ and another that ‘when it was finished, one would jump from foot to foot in an attempt to ease the excruciating pain while racing back to one’s room. After several minutes of dancing the pain would start to ease.’ After that came the traditional display of injuries:

‘The stripes on one’s bottom would be examined by one’s peers. A judgment on the accuracy and blueness of the stripes would be used to compare the relative merits of the Prefects in administering these badges of pride.’

Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

Attitudes to punishment

So how did the Wellingtonians of the 1940s and ‘50s feel about the beatings and other punishments they received?

Overwhelmingly, as with fagging and other practices of the time, most said they ‘just accepted it’ and that it was ‘part of life.’ Several pointed out that they were already used to being beaten at prep school, and indeed some felt the Wellington version was less severe!

‘Beatings were accepted as a fact of life. It was odd if one never had one.’ Sam Osmond (Hill 1946-51)

‘Beating was part of life and a hazard to be avoided. I never questioned the rights and wrongs of its existence… I was fatalistic rather than angry.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘One knew pretty well which were “beatable offences” and tried to avoid getting caught too often.’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

Some felt that beatings were preferable to other forms of punishment:

‘Boys would prefer beating to a punishment which took up time, such as extra land work or memorising lines.’ John Watson (Benson 1946-51)

‘Beatings were usually regarded as a quick end to a discovered misdemeanour, rather than a more drawn-out punishment or a report to higher up.’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

And they did earn respect from one’s peers:

‘“Six of the best,” administered by a master or Prefect, could be seen as a rite of passage.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘Nobody liked punishments, giving or getting, but if it wasn’t for something nasty (stealing or beating up younger boys) then one could even be a “hero” the next morning while everyone waited at breakfast to see if you could sit down without wincing!’ Robin Lake (Benson 1952-57)

So much so that a lack of stripes could be disappointing:

‘It was a very mild caning which he administered backhand in two casual strokes. Later in the changing room, friends as ever came over to examine the bruises. Usually there were colourful weals to admire, but this time, there was no mark at all, and my friends were not impressed. My friend and I should have felt happy about this mild caning, but instead we somehow felt cheated.’ Richard Wellesley (Benson 1948-53)

Although all saw the need for a disciplinary system, and almost everyone accepted beatings as a valid form of punishment, individual instances were resented if felt to be unfair. It is interesting to read how students made the distinction:

‘I did feel that a beating for walking on the grass in the Quad was somewhat Draconian.’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘I remember two: once by Mr Penfold for disrupting a PT class, justified, and once for reading in bed after lights out. This I thought was unfair.’ Tim Travers (Hopetoun 1952-56)

‘I failed the fag’s exam and received a beating from a Prefect. I did not feel that was fair but accepted it as the way things were. I felt the same way about being beaten for “squealering” in the lineup outside the Dining Hall, but being beaten by a master for academic performance was unfair and left me quite resentful.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954-57)

‘I did once get beaten for attempting to skive off the Kingsley run – a fair cop I have to admit!’

Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

‘I deserted the College rugby match a minute or two before the end in order to rush with a friend to Grubbies to be first in the queue for ice creams. I richly deserved this beating as it was clearly right to cheer the College team at the end of the match.’ Richard Wellesley (Benson 1948-53)

An effective deterrent?

Was beating effective in discouraging certain behaviour? Some certainly thought so. One anonymous contributor wrote that ‘Beating was an excellent deterrent. After a good thrashing, one thought twice before repeating the same offence.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55) admitted, ‘I was terrified of being beaten and went out of my way to comply with the many rules.’

Others disagreed. Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56) gave his opinion that ‘Beatings should have been banned years before. They did not achieve anything and were degrading for both parties.’ Michael Crumplin (Orange 1956-60) used the same word to describe his feelings: ‘It conjures up difficult recollections. It was painful… I had blood drawn once. It was most degrading.’ Several more stated that although they had accepted the system at the time, with hindsight they were glad that things had moved on and that corporal punishment was no longer practised.

The other side of the story

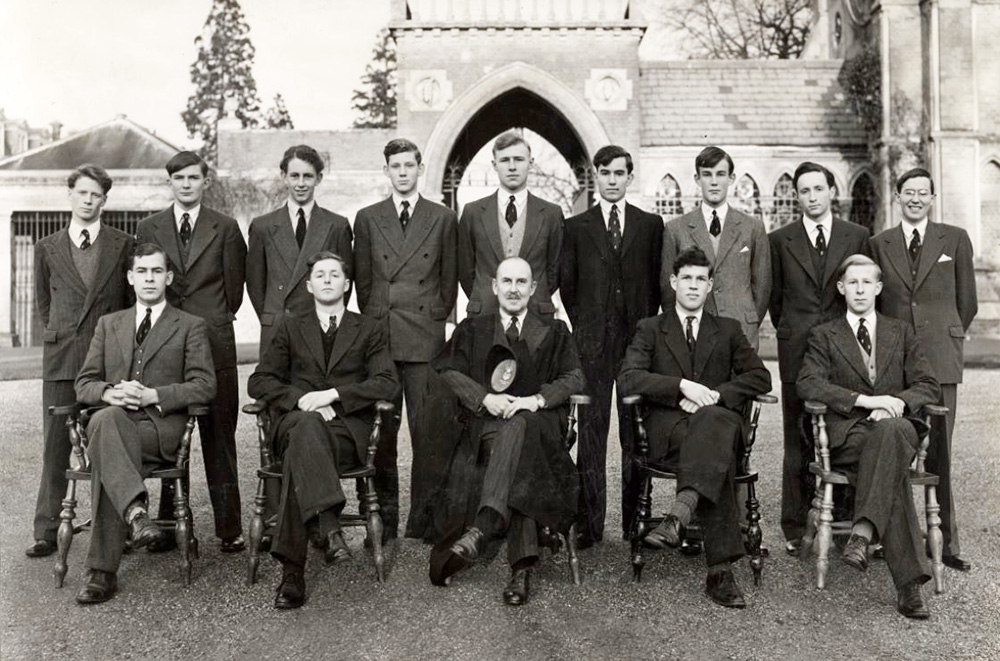

Most of our respondents were never in the position of authority required to beat other boys. However, those who became House or College Prefects or Heads of House were empowered, and indeed expected, to do so. How did they feel about this responsibility?

Abuse of the system appears to have been few and far between, although there were a couple of accounts of those who relished their powers:

‘The only exception was a particular College Prefect who vowed to beat a boy with every initial surname from A to Z. With a hyphenated name I was lucky to escape unscathed!’ Richard Godfrey-Faussett (Anglesey 1946-50)

‘I recall one who used to place a chair (over which the culprit bent) at one end of the long corridor that ran between the “tishes.” He would then go to the other end and sprint back, maximising the damage he could inflict.’ Anonymous

‘The Head of House with great glee practised caning on the cushions, known as “hard-arses,” in the small community room at Upcott, declaring, “You’d better behave or this is what’ll happen to you!”’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

Only one, very honest respondent confessed to feeling ‘at the time, a certain vanity and superiority’ at being given the responsibility of beating, although he considered ‘in retrospect, it’s a good thing that it is now forbidden altogether.’ Most in the older cohort appeared to accept, but not relish, the duty:

‘The responsibility to administer corporal punishment with fairness and careful adherence to school rules was taken very seriously.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘As a Prefect, one felt no compunction over caning, but rather an uncomfortable responsibility.’

Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘As a Dormitory and College Prefect, I occasionally beat a malefactor but have no memory of who or why except that we shook hands afterwards… it was just another duty as a senior boy.’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

Others were more ambivalent:

‘The punishments I had to administer – mercifully very few – did not worry me much, though I did not beat very hard and was always glad when it was over.’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

‘As Head of House, I only recall twice beating anyone. I didn’t particularly approve of corporal punishment but didn’t disapprove sufficiently to refuse applying it.’ Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54)

And many remember disliking the task at the time:

‘I always disliked this but regarded it as part of my duty.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘As Head of House, I only beat twice. The second boy turned after I had finished and said, “I think that hurt you more than me,” and he was right.’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

‘As a College Prefect, I beat a younger boy. It was a horrible experience for me and I never beat anyone again.’ Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941-45)

‘As Head of House for two terms, I administered very few beatings and later wished that I had abolished the boy-inflicted practice altogether.’ Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

‘I hated the boy system, both as a receiver and a giver. As Head of House, I felt that I should inflict at least one beating, lest I was thought to be a cissy and too lenient; but it gave no satisfaction.’ John Le Mare (Stanley 1950-55)

‘I was never happy about this as it seemed altogether a rather pre-historic type of punishment; each time I inflicted it I felt rather guilty, as it seemed a bit like a senior boy bullying a more junior one.’ Christopher Birt (Beresford 1955-60)

Even some of those who felt no qualms at the time, later had doubts. Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46) wrote: ‘I am uncertain about the justice of the beatings I administered; sixty years later, I still have a feeling I was unfair.’

One anonymous Head of House told of how he circumvented the duty: ‘I did not think the two junior boys’ offence was very serious, so I took a cushion up to the dormitory bathroom and saw one, admonished him and told him to hold the cushion. I gave it three loud whacks so that his chum could hear them and sent him down, rubbing his bottom! The other came up and was admonished as I knew the waiting downstairs had had the desired effect.’

While a few encountered practical difficulties:

‘I had two tries at beating. First was a boy who had failed to post the letters to parents, later found crumpled in his pockets. After one whack he leapt up and ran screaming around the room. No amount of suggestion that his father would be ashamed of him was any use, so I gave up. The next was my younger brother Paddy, who apprised of my intentions appealed to the House Tutor on the grounds of filial involvement and his appeal was upheld. I never tried again.’ Peter Cullinan (Benson 1948-52)

‘I only beat one boy, who said it didn’t hurt, which upset me!’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

Phasing out

By the later 1950s, some thought beatings by Prefects were starting to become less common at Wellington:

‘I don’t recall boys being beaten in my later years. Perhaps it was stopped, at least in the Combermere?’ Nick Harding (Combermere 1951-1955)

‘When I achieved the status of Dormitory Prefect, the power to beat had been removed and reserved only to the Head of Dormitory.’ Jerry Yeoman (Anglesey 1955-59)

‘I suspect the 1950s saw College becoming generally more humane. As a College Prefect, I had the authority to beat a boy disobeying the rules. It was a power I never sought to exercise and I was not alone in adopting an anti-corporal punishment approach.’ Richard Merritt (Picton 1954-59)

‘We in the Hardinge made our own contribution without guidance from above. In my first term there were about twenty beatings in the Hardinge and in my last year, (just) two… So, we made big changes by ourselves and I’m proud that we left the place better than when we found it.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

Expelling – the ultimate punishment

Very serious misdemeanours might merit the ultimate sanction – being expelled. This does not seem to have been common, but features in the following story by William Young (Anglesey 1954-58), who narrowly escaped that fate:

‘One Summer Term (1957?), four of us bicycled over to Eton one night and painted the cannon outside the Provost’s Lodge, hanging a sign on the door, “One reconditioned cannon for sale, apply within.” A week later the Master ‘Gus’ Stainforth read the school an ultimatum, to the effect that any boy breaking bounds would be severely dealt with. When the other three planned another expedition, I declined. They duly went off to Charterhouse and painted footsteps from the founder’s statue in the main quad to the toilets in the nearby cloisters and back to his plinth.

‘In due course, the three were identified, and there were rumours of a fourth miscreant. The three were invited to leave at the end of term, and I felt it wrong not to share some punishment. I, therefore, owned up to the first expedition and was commanded by GHS to make a rendezvous with the Head Boy… This resulted in ten strokes, delivered with enthusiasm, by him.’

Of course, if one had already left, the school had no sanctions to apply:

‘A very late-night visit from Oxford with two other OWs, accompanied by a very fetching mannequin dressed in a bikini, a sword, and a notice saying “Uniforms by Moss Bros”! We “borrowed” a ladder from the workshops and in fear and trepidation climbed over the fence into Combermere Quad, where she was cemented into place at first floor level in the empty niche between the windows of the Hardinge. It was a miracle that we woke no one; and a shame that we could not be there to enjoy the reaction.’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)