The Master

To most Wellington students of the 1940s and 1950s, the Master was a remote figure who had little impact on everyday life. Most viewed him with respect, some even awe. Nevertheless, each Master had a profound effect on the school, its direction and atmosphere.

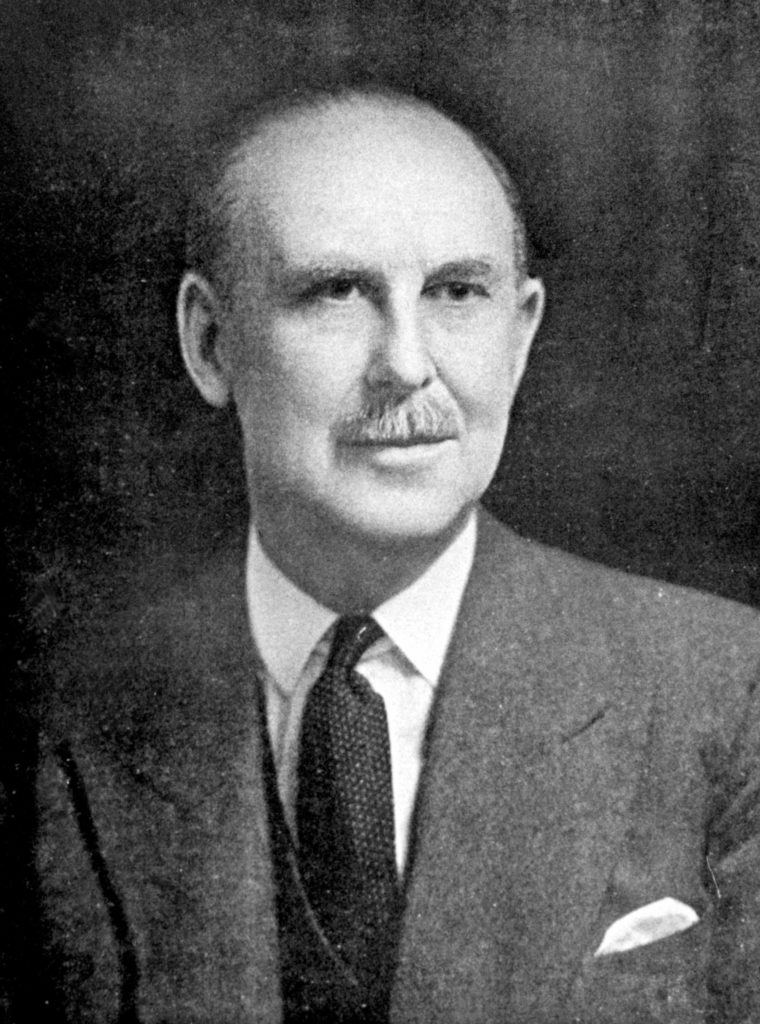

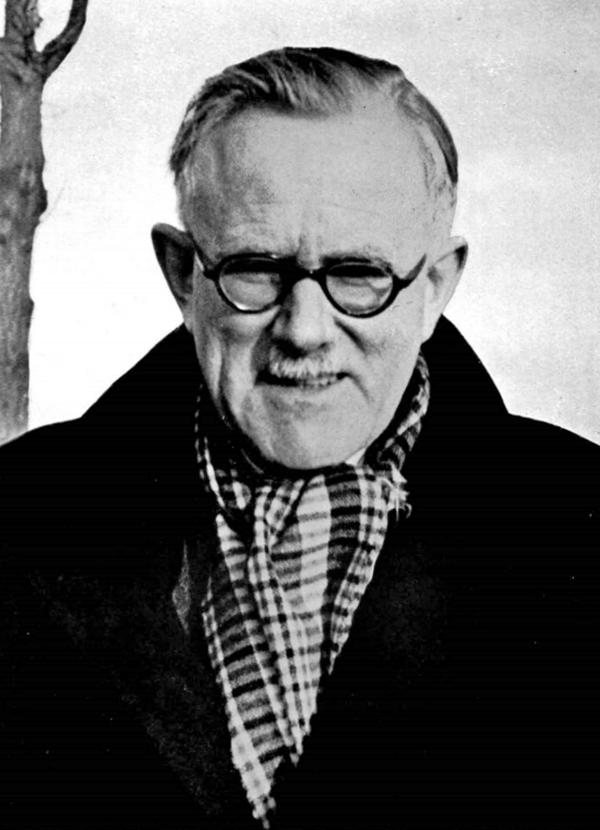

R P Longden

The oldest of our respondents, John de Grey, now Lord Walsingham (Blücher 1938-43) remembers Wellington’s sixth Master, ‘Bobby’ Longden. Appointed in 1937, Longden was relatively young, charismatic and seen as a moderniser. Walsingham’s one personal encounter with him, although brief, was clearly memorable:

‘We processed in nominal roll order into the Chapel and out again every day, and Bobby Longden sat facing the column of boys with the roll in front of him, turning the pages discreetly as we passed. By the end of his first term he knew every boy by name – there were 650 of them. At the very beginning of his second term, I was returning from the tuck shop when I was alerted to his approach. Whenever a boy passed an usher, he had to “tick” him. It was the first time he had come across me, so I gave him my very best performance. Believe it or not, so did he, remarking as he passed and looking me straight in the eye, “Good afternoon, de Grey.” You did admire the Master, and if he actually knew who you were it made your day.’

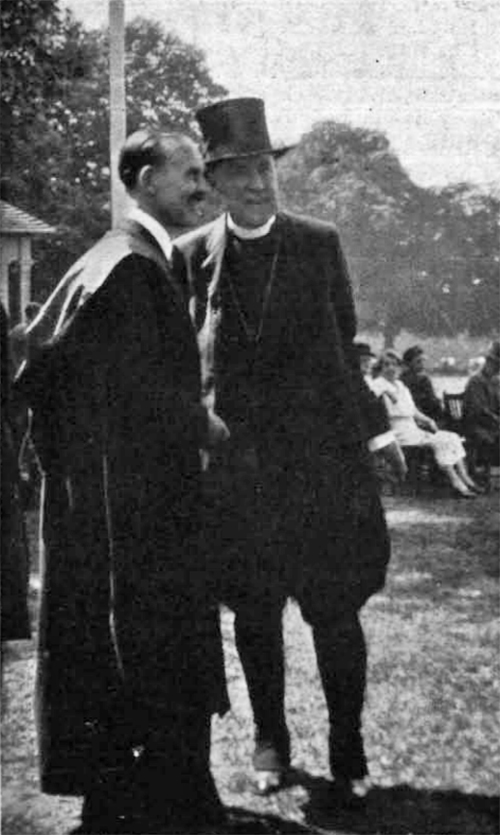

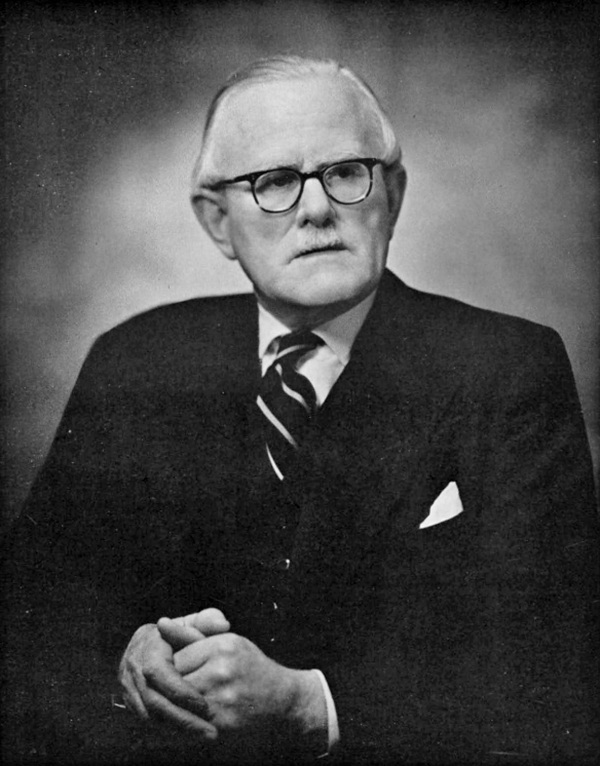

H W House

Longden’s death in an air raid in October 1940 was a huge shock to the school. Several respondents mentioned the difficult circumstances in which his successor, H W House, took over:

‘H W House, one of the “old school” who took over shortly after the younger and much more progressive Longden…’ Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47)

‘Longden had been enormously popular… Harry House therefore had a hard time making his mark among a large number of boys who worshipped his predecessor. We certainly judged him most unfairly on the grounds that he appeared to lack confidence when speaking in public. We used to count the number of times he said “um” in an address.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘Mr House was the Master in all my time. There was very much a feeling that he had taken over after the tragic death of Mr Longden in 1940 and had saved College.’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

A remote figure

The head of a school such as Wellington is perhaps always somewhat removed from the daily life of the students. In the 1940s and 1950s this was certainly the case, as mentioned by most respondents:

‘Wilfred (known as Harry) House was a somewhat remote figure in my early years at College. I remember him chiefly for taking prayers every Wednesday in Old Hall, when he used the occasion to make announcements.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘Apart from seeing Major House at Chapel, and once a week when he would address the whole school in Old Hall, I only saw him walking about, head bowed. He never spoke to me once during my time at College except to say “Goodbye and good luck” on the day I left.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55)

‘He seemed to be forever walking College corridors carrying books on Classics. Otherwise he appeared to play no part in the school curriculum.’ Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52)

‘I probably spoke to him three or four times. A remote figure. Great pity as he seemed a nice man. He never visited our dormitory or met parents.’ George Nicholson (Hardinge 1949-54)

‘I saw him once or twice a year but never talked him or knew what he did. A dapper ghost.’

Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53)

‘I met the Master, Harry House, rarely, and more as a result of tennis in the holidays than any College reason.’ Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53)

‘Harry House had little effect on my life that I remember.’ Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941-45)

‘Neither Harry House nor Graham Stainforth ever spoke to me in my three and a half years, something I have never forgotten!’ Tim Shoosmith (Blücher 1953-57)

‘Mr House would not have known of my existence.’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58)

Respected

For some, this sense of remoteness bred respect. Mike Bolton (Hopetoun 1947-53) commented ‘We held H W House in awe,’ while John Ravenhill (Orange 1953-56) called him ‘A great leader of us boys.’

Charles Enderby (Picton 1953-57) remembered him as ‘an immensely respected figure, quiet and dignified,’ even though ‘we never knew of his great courage in the First World War.’ On the other hand, one anonymous respondent felt that this history definitely helped House’s reputation:

‘In a society which tended to judge every man by his military record, he enjoyed our total respect and regard. “Wilfred” as he was known behind his back, had been awarded a DSO and MC in the First World War and was as excellent a headmaster as he had been a soldier. Like so many strong men, he was gentle, courteous and softly spoken.’

Ridiculed

Others, however, felt differently. Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48) described House as ‘ineffectual,’ while Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51) wrote ‘Mr House was uninspiring and always seemed to most of us as a rather silly little man.’

One mannerism in particular was often ridiculed by the boys:

‘Sadly he was prone to “umming” and “erring” when addressing us boys in Old Hall every Wednesday, and this provoked imitation in private.’ David Nalder (Orange 1949-53)

‘He was known for his speech impediment, and the boys used count his “ahs.” The record was 140 in ten minutes.’

Hardy Stroud (Combermere 1950-55)

‘He was a rather shy man without huge presence. He was hesitant in public speaking with “ehs” and “ahs” punctuating every sentence. This made him easy to mimic and probably reduced his authority.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

Character

Undoubtedly, House’s personality did not make it easy for the students to get to know him. Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48) described him as ‘shy and hesitant,’ while Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48) considered him ‘rather self-effacing.’ However, all those who had the opportunity to know him better remembered him with a great deal of warmth:

‘I had a great respect for him as a sincere and fair man. Probably his personality was not ideal for a headmaster as he did not enjoy the limelight, but he performed well for Wellington.’ John Watson (Benson 1946-51)

‘Harry House was friendly, open and visited boys in their Houses and Dormitories –I recall well two such visits.’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘I liked Wilfred House a lot, because he was kind.’

Anonymous

‘Mr House – a real gentleman.’ Michael Campbell (Hill 1954-59)

Some knew him as a teacher:

‘I had History with him one year and he was a very thorough and entertaining teacher.’

John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘In the term at the end of which I took School Certificate, I was taught French by the Master, Harry House. He was a good teacher. I liked him and did well in his class.’ Charles Wade (Lynedoch 1947-50)

‘I was in his French set for a term or two, and thought he taught very relaxedly and with a kindly manner.’ Michael Hedgecoe (Combermere 1951-54)

Others grew to know him by being Prefects, or through family or sporting connections:

‘Harry House was a kind man, whom I got to know a little through my friendship with his daughter (tennis on his private court on summer Sunday afternoons).’ Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54)

‘When I was fourteen, I played golf in the third (and last) couple for the Boys v The Common Room. Harry House was one of the opponents. He had learned the game at Dornoch where he went for summer holidays when a boy. He said he had gained a handicap of 4 and I believe him, for his swing was good. Alas he now never played, and on the first tee, up came his august head with the ball barely travelling twenty yards. My partner and I won by the indecent margin of 6/5 but he never held this against me! A thoroughly good man!’ David Nalder (Orange 1949-53)

‘Harry House was in my opinion an excellent leader and was, I believe, much respected by both staff and pupils. I got to know him quite well, as he and his family were friends of my grandparents. In my last year I spent quite a bit of time, together with the Head of College, talking to him about the goings-on within the school and how it was operating – he was a very good listener as well as being a good, if somewhat low-key, speaker.’ Colin Mackinnon (Hardinge 1951-56)

‘I think that in many ways in the histories of Wellington that have been written so far, he is the most unfairly underrated Master the school has had. It was as a Prefect that I really came to appreciate some of the challenges that he had faced when he first arrived at Wellington… among other things, the infamous case of boys raiding various shops in Crowthorne and storing the proceeds in the Orange Tower! That inevitably led to the expulsion of the boys concerned. On my leaving Wellington, House and his family became lifelong friends, up to the deaths of him and his wife and beyond with his children.’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

Although occasionally, these associations gave rise to embarrassing situations:

‘Harry House became a very good friend. I fancied his daughter and took her out two years after leaving. I took her somewhere quite smart in town in my Dad’s old Land Rover. I think that I must have overplayed my hand as we did not go out again…’ Anonymous

‘On one occasion, House took me in his car to watch an away rugger match. On the journey I felt very car-sick. Rather than pollute the Master’s car, and too embarrassed to ask him to stop, I was sick into a brand new pair of sheepskin gloves which my parents had given me for my birthday. They were never the same again!’ Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953-58)

Personal interest

Several respondents were impressed by the personal knowledge House had of his students, and his interest in them:

‘Mr House was a very decent person, seemingly always quietly in the background, who had the rare gift of being able to remember the names of most of the boys.’

Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47)

‘He had the remarkable gift of seeming to know all boys’ names. He knew mine!’ Anonymous

‘He was quick at learning names. This was epitomised for me when my eldest brother’s name was put up in Chapel, when he had been killed in the RAF. I was walking through the Lower Combermere Quad when the Master, coming towards me, stopped me and said how sorry he was to hear the news as he had taught him at Oxford. I was very touched that he had picked me out – at a sad time, it was very helpful.’ David Simonds (Orange 1941-46)

‘When I was invalided out of the Army while at Sandhurst, my father took me to see him in order to obtain advice as to what I might do next. Major House took a touching concern in my welfare, which both impressed and encouraged me. I retain the impression of a kind and considerate gentleman.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

‘When I was made a member of the Upper Ten and subsequently Head of College, I saw quite a lot of him and grew to like him very much. Sitting next to him at lunch in Hall, he would surprise me by showing that he knew the names of most of the boys sitting at dormitory tables in front of us. He also knew a lot about them and showed compassion about those with problems.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

Spiritual

Some were struck by House’s spiritual side:

‘He read the Bible very well.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘From his prayer sessions I got the impression he was a very religious and decent man.’

Tim Travers (Hopetoun 1952-56)

‘He was the least eloquent of men, who could not utter two words without the sound “uh”, so he was known as “uh-uh House.” But I can still feel the great intensity with which he read 1 Corinthians 13, which he often did. It was as though all the terrible carnage of the war, and the unhappiness of the staff room, had focussed his faith on the words “Now abideth, faith, hope charity and the greatest of all is charity.”’ Richard Harries (Hill 1949-54)

Discipline

Although quiet and reserved, House could exert discipline when necessary, as recalled by Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56):

‘Just once, when boys had taken command of the roundabout in Lower Crowthorne and pelted all the traffic with snowballs, was he truly incensed, punishing us with the loss of a half day, I seem to recall. That day he lost his hesitancy.’

Most seemed to think that House hit the right note when dealing with offenders:

‘Harry House always seemed a gentle person… I was summoned to see him twice. The first time was when I sent circular letters (the kind that made you a fortune if everyone did as bid and sent £1 to the person at the top of the list, then to 10 others etc) to several people who went on from my prep school to Eton. The second time was when caught with a bottle of sherry in my very last week, bought to celebrate winning a cock match or similar. He made me stay behind for several hours on the day we broke up, and to copy out “lines,” something I had only heard of happening to the likes of Billy Bunter. I didn’t hold it against him.’ Nick Harding (Combermere 1951-1955)

‘It was traditional, at the end of the Summer term, for some sort of College prank to be carried out. One of the young masters had one of those tiny, fabric-bodied Austin 7s which was parked outside the main entrance. On the last day of term it was missing. One did not have to look far to find it: it was perched on the roof of the Anglesey. The Master appeared in the Dining Hall at breakfast and made an announcement, requesting “the gentlemen” who had put Mr Wilson’s car on the roof to get it down again undamaged, in which case no further questions would be asked and everyone would be free to go home. Within half an hour the little car, immaculately polished, was restored to its normal parking spot. How they had manouevred it up and down three flights of stairs and out onto the roof, I have no idea. The Master, of course, recognised that no harm had been done and that “the gentlemen” responsible were likely to go on to have brilliant military careers. It was typical of his “no fuss” approach.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

Advice

Perhaps a measure of House’s success is how many boys remembered his advice to them, so many years later:

‘I particularly remember his talk to the leavers on our last day at Wellington. He made two points that I clearly remember. The first was that it was very important to marry a woman who could share your interests, as well as being the object of your love. He said that he had been very fortunate in this way and he hoped we would be too. The second was that there was a link between alcohol and lust. “Wine,” he said – and I remember his exact words – “was made to make glad the heart of man,” but it should not be abused, as it could lead you into trouble. His first injunction I rigorously followed; the second, along with most of my university friends, I did not.’ Richard Wellesley (Benson 1948-53)

‘More than most similar talks, I remember the essence of House’s message when he spoke to us as a group of leavers. What he said was sound enough: we were going out to lead, and should not abuse our status. He spoke of a man with a large cigar who ignored the “No Smoking” signs on touring a factory, thereby losing respect in the eyes of all who saw him.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

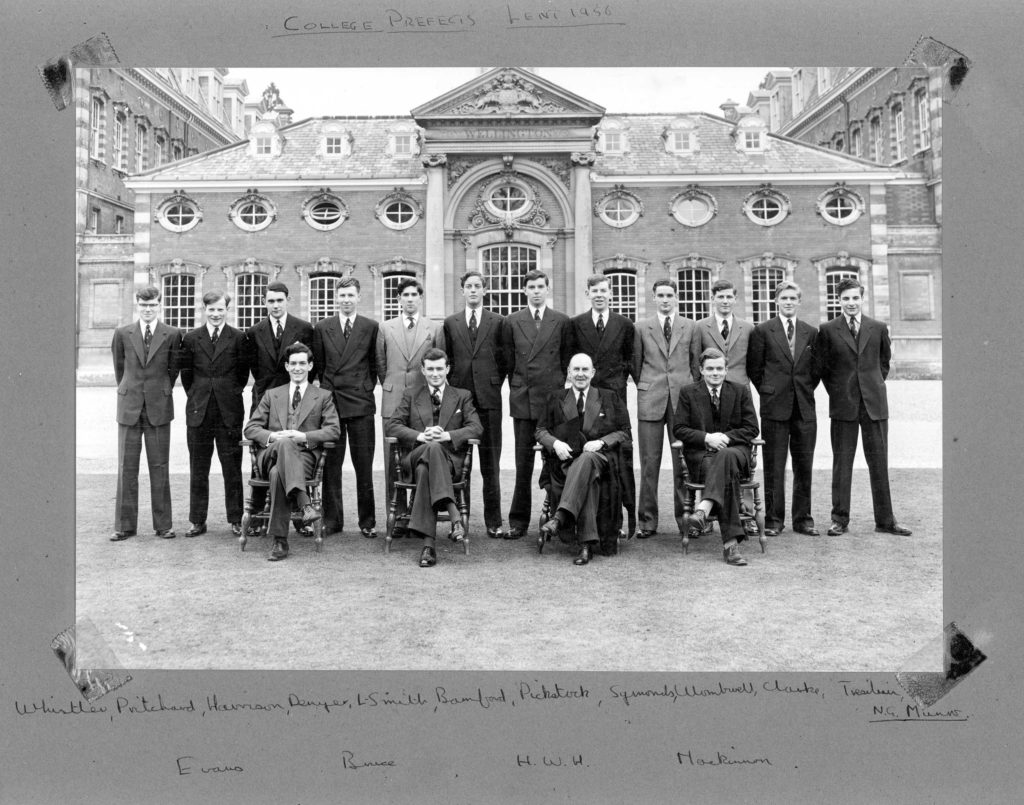

‘Of Harry House I have just one memory, of a piece of advice that I have tried with mixed success to put into practice in life. Two or three of us had just been appointed College Prefects, and were summoned to him for a pep talk. “Always remember,” he told us, “that the greatest force for good in the world is the force of example.” Not a bad philosophy.’

Neil Munro (Talbot 1952-56)

‘At the end of our time at Wellington, he gave an address to the leavers. I can see him as I write this. “You have,” he said, “been very privileged to have had five years at Wellington. The experience will benefit you for the rest of your lives. You must understand that what is important is what you contribute to society, not what you can get out of it.” Wise words from a fine Master.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

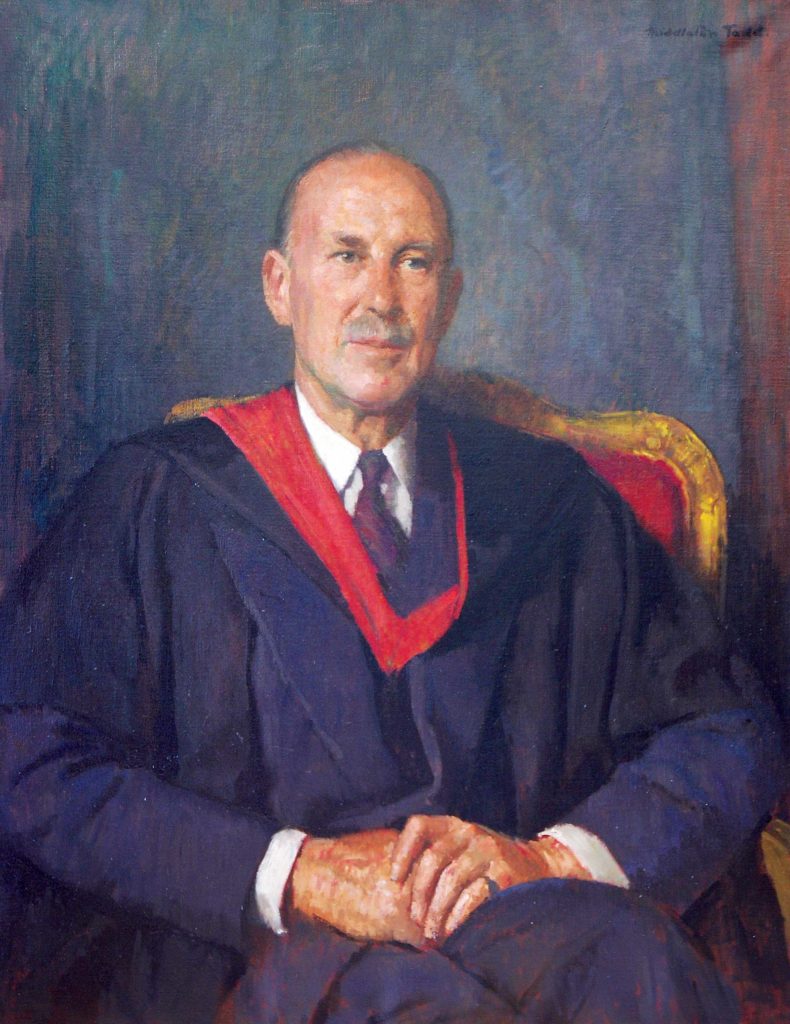

G H Stainforth

In 1956 House retired, to be replaced by Graham Stainforth, who had previously been first a student and then a teacher at Wellington. His manner could hardly have been more different from that of his predecessor.

Roger Pinhey (Hopetoun 1952-57) described him as ‘unapproachable,’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58) as ‘very austere and rather frightening,’ and Michael Crumplin (Orange 1956-60) as ‘stern, unsmiling and very strict.’ Stuart Dowding (Talbot 1957-61) recalled ‘being scared stiff of Gus Stainforth, under whose seat I sat in Chapel.’

Perhaps even more than House, Stainforth seemed distant to many:

‘Even when I was a School Prefect, I suspected Mr Stainforth did not know who I was.’

Michael Campbell (Hill 1954-59)

‘My recollection of “Gus” Stainforth is one of a remote, austere figure, slightly stooping, stalking the colonnades, clutching to his side his mortar board. I have subsequently been told that he forbade any other staff member from carrying a mortarboard as he used it as a symbol of office, of his status and of his authority. A bit like a sergeant major’s pace stick!

During my entire period at Wellington I spoke to the Master only three times, twice regarding societies’ events. The third occasion was on my penultimate day. I had been instructed by a member of staff to “say goodbye to the Master”. I duly ambushed him in a colonnade and explained my interruption of his perambulation. He had no idea who I was, of my name, or even my dormitory.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

‘Stainforth transmitted gravitas combined with a stern manner. His voice had a nasal tone. I think we were all rather spellbound when he addressed us at the weekly gathering in Great Hall. I do not recall him ever lightening the occasion with anything approaching humour.’ Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60)

Discipline

Most respondents felt that ‘Gus’ (a nickname quickly adopted all, from the apparent reading of Stainforth’s neat initials) deliberately set out to tighten up discipline, perceived as lax under House; and several had specific memories of being on the receiving end of this, one even after leaving Wellington:

‘From a Sunday ‘Leave Out’, I returned my younger brother late for Evening Chapel, because of a car breakdown, and was obliged, therefore, to write to the Master, to apologise for not having arrived back on time. The letter, subsequently seen by my brother, was marked, by Stainforth.“I suppose that is an adequate apology for a Green.”’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘Our English class sometimes took place in Stainforth’s office. On one occasion he was away, and we were supposed to read a selected book. One member of class, looking for something more interesting to do, approached Stainforth’s desk and opened the top drawer, from which he extracted some highly confidential notes about a boy who had absconded. He read these out. Shamefully, none of us stopped him. That evening one member of the class told his Head of House what had happened. The Master was suitably informed.

Understandably Stainforth was absolutely furious and summoned us all to Mr Storrar’s classroom where he gave us a dressing-down which was explosive to say the least. I had never seen anyone so angry. I can’t remember our punishment but I do recall his final words, which were to the effect that when we left College he had no wish to shake our hands. I’m not sure that I was ever on good terms with him after that, but as School Prefect I saw a lot of him in my last year and his comments in my final report were generous.’ Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953-58)

Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59) remembered Stainforth’s address to leavers as very different in tone to that of House:

‘He swept in attired in formal cap and gown. “When you leave here,” he barked, “you will meet young women who wish to sleep with you. It is my advice to you: do not fornicate! DO NOT FORNICATE!” And he swept out. That was it. That was his farewell in its entirety!’

Differing views

But there were those who mentioned his more positive qualities. John Thorneycroft (Benson 1953-58) considered him ‘a very capable administrator,’ and an anonymous OW had a particular memory of ‘his reading of lessons in Chapel at the beginning and end of terms – Romans and Ephesians – his voice and delivery were well suited to these Pauline exhortations, exceptionally beautiful as they are in the Authorised Version.’ William Shine (Hill 1956-60) remembered him as a ‘nice chap, even though he once called me into his study and told me not to waste my father’s money by slacking or else I’d have to leave.’

A few respondents, who felt they had got to know the Master, expressed warmth towards him:

‘I came to know the Master, Graham Stainforth, well. He looked something of a “sobersides,” but I found him to be kind and agreeable.’

Christopher Miers (Beresford 1955-59)

‘In my last two years at Wellington I got to know Graham Stainforth tolerably well; this began when, as Head of Douro, I invited him to come to meet all the boys there one evening. I recall that I felt that I should entertain him in some way, but the best I could do was to offer him a fruit jelly, which (unsurprisingly) he refused! Most of my contemporaries had a great affection for his predecessor, Harry House, and they had a tendency to see Stainforth as a very dour character in comparison, but I liked him, respected him, and got on with him.’ Christopher Birt (Beresford 1955-60)

Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59) recounted a surprising incident after he had left College:

‘To my everlasting astonishment he wrote a letter to my mother in which he apologized that Wellington had not encouraged my artistic abilities. From now on, he wrote, Wellington would fully encourage the arts, especially theatre.’

And a few contributors reflected, with the benefit of age, on Stainforth’s motivation:

‘House had allowed Wellington to become slack… Stainforth needed to shake the place up, which he did. [In later life] he told me that WC was shambolic when he got there so he had to be a disciplinarian.’ William Shine (Hill 1956-60)

‘I have always believed that GHS had a philosophy to maintain the status quo. Whilst acknowledging the austerity of the 1950s, it seemed to me that he fought change, I assume because he remembered College as it was when he was a Foundationer (1920-25), and subsequently as an usher and tutor (1935-45). Maybe I have done him an injustice?’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)