Snacks, Treats & Grubbies

It is generally accepted that teenage boys are always hungry, and the Wellingtonians of the 1940s and 50s were no exception. We received numerous accounts of how the regular school meals were supplemented by all manner of snacks and treats.

‘Swipes’, brew-ups and tuck boxes

‘Swipes’ is a peculiarly Wellingtonian phrase, and one known to generations. Originating as a supper of bread, cheese and small beer, it takes its name from a 19th century term for poor-quality or stale beer.

By the 1940s, ‘swipes’ was firmly established as a daily ration of bread, margarine and jam, which was collected from the kitchens and taken back to the dormitories, there to be toasted by means of various ingenious contraptions.

‘We had “swipes” (bread and marge) to take back to the dormitory, to fill any gaps, providing there was enough bread to toast for prefects at breakfast!’ Anonymous (1951-56)

“I remember “swipes” being brought up to the dorm at 9 o’clock each evening – sliced bread with some sort of spread, and milk which I would use to make chicken noodle soup from a packet… there was a gas ring outside the dorm on the stairwell. Salubrious?’ Vernon Phillips (Murray 1951-54)

‘The toast fag made toast over crossed wires in an old biscuit tin over a single gas ring.’

Stuart Dowding (Talbot 1957-61)

‘”Swipes” (a bin of bread, margarine and jam) would be delivered to the end of the dormitory corridor each evening, but in the early years there was little chance of getting one’s teeth into any of it. My mother claimed that a PS to my weekly letter home once read “Please send some bread, however stale.”’ Ross Mallock (Murray 1954-59)

And one anonymous student (1950-54) remembered an additional ration: ‘In the evenings, before bedtime, a fag could be sent to the kitchens to collect a lidded pail of thick, brown soup which was always exactly the same and which was nice and warming on a cold evening.’

Most students received from home, or were able to buy, simple tinned foods with which they supplemented their ‘swipes’ and elevated them to the level of a ‘brew-up’ by means of the dormitory’s solitary gas ring. Baked beans, powdered eggs, and sometimes Spam seem to have been favourites here.

‘The gas brew-ring was popular for preparing extra rations and must have heated up many tins of baked beans per term.’ John Watson (Benson 1946-51)

‘We also used to brew up omelettes made from powdered egg on a gas-ring just outside the dormitory.’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘On a Sunday afternoon, we were allowed to use a gas ring, and in my case I made porridge and ate it with black treacle.’ John Ormrod (Stanley 1946-50)

‘Hall meals were supplemented with tins of baked beans brought from home and toasted “swipes” bread, thanks to the dormitory brew ring. One budding chef wanted to see what would happen if the tin were not punched as per the instructions. The resulting explosion was most satisfactory, but there was an awful lot of cleaning up!’ William Field (Lynedoch 1952-56)

‘Each dormitory had a solitary gas ring outside its doors, at the head of its staircase. Black with the congealed fat of ages, it was a temperamental as well as unhygienic device, but it served to brew watery, powdered-milk cocoa and occasionally a powdered egg scramble, sometimes with beans in brine on the side. Fags were employed to scrape out the burnt saucepans which our culinary efforts usually produced.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

‘The custom was to “brew” with friends on Saturday evenings on a small gas ring in a brew room downstairs. Baked beans, spaghetti, fried eggs, sausages and fried bread were the main staples.’

Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

‘Baked beans and Spam became a favourite of mine.’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954-59)

‘Cheese toasties cooked in a clamp over a gas ring were a regular snack between meals and there were experiments with ginger beer, which eventually blew up despite strict supervision.’ Adrian Stephenson (Talbot 1957-61)

‘I used to have Bird’s custard to cook or a haggis sent from Scotland. Some cooked condensed milk to make a sort of fudge as a sweet.’ Ian Nason (Orange 1950-54)

‘Food OK, but not enough, so a couple of us regularly bought a sack of oats from the kitchen which we ate in the evening.’ Tim Travers (Hopetoun 1952-56)

Some even foraged to supplement their diet. Charles Enderby (Picton 1953-57) wrote: ‘In summer, I would collect moorhens’ eggs from the Blackwater and eat them hardboiled.’

Sometimes the cooking initiatives were carried outside the dormitory:

‘I do remember one exceptionally cold winter when oil-fired stoves were set up in the laboratory where we were learning Physics. A couple of us brought tins of baked beans into class and heated them up on the stoves. We then managed to consume them while our teacher had turned round to write on the blackboard.’ Colin Mackinnon (Hardinge 1951-56)

As mentioned, many relied on foodstuffs sent from home for the ingredients for their brew-ups.

Most had a lockable tuck box, which would be brought to College full at the beginning of each term. All too soon, its contents would be finished. How frequently they might be topped up by parcels from home depended on the generosity and, in some cases, the financial status of each boy’s parents, not to mention availability due to rationing. However, little luxuries were often shared with those less fortunate.

‘My salvation was the tuck box which my mother filled for me at the start of a term. That kept me going for half a term – thereafter I bought snacks from Grubbies.’ John Hornibrook (Murray 1942-46)

“I used to be sent back with a 48 pack of Penguin or something similar that might last three weeks.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘My mother also sent me by post a weekly sponge cake that was ordered from a supplier as I was always hungry.’

Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953-57)

‘I mentioned to my parents about always being hungry, so my mother arranged with her butcher to send me packages of bacon every week, which I could fry up on the gas ring in dormitory. This worked well until one summer I opened the package to find a wriggling mass of maggots. My bacon subscription was cancelled for the rest of that term.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954-57)

‘I received a weekly parcel from the Army and Navy Stores in London; a packet of bacon, butter, sausages, and savoury biscuits. This made me very popular!’ William Young (Anglesey 1954-58)

‘Most tuck boxes were empty after the first week, and any subsequent replenishment was welcomed as much by friends as by the recipient since, by custom, he was bound to share it. Some boys returned to school with tins of orange marmalade, peanut butter, and even Spam.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

‘We shared occasional luxuries (I recall my grandmother once sending me a parcel of Bath buns!) One high point was the occasional arrival of a food parcel sent by a sister school in New Zealand. Lots were drawn across the house for the contents, one could be lucky enough to win a tin of meat or even butter.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

Grubbies

A Wellington institution, Grubbies was fondly remembered by almost all our respondents as a rare source of edible treats, as well as a congenial place to relax with friends. Only a handful stated that they seldom or rarely visited. Those at College in the 40s remember how sweet rationing was handled:

“We had coupons for 12 oz of sweets a month, 4 oz one week and only 2oz the next.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘Initially, it was a matter of going there to use our sweet coupons, and thanks to our parents there was money in our accounts there, so that cash was not needed. I remember well when rationing ended, sometime in 1953, I think, and we could buy extra sweets – no doubt boosting tooth decay in the young population!’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

‘In February 1953, sweets came off the ration. For the previous 10 years, the allowance had been 12 oz per person per month, which at Wellington we claimed with coupons, which were highly negotiable currency, and were issued at the beginning of each term. When rationing ended, Grubbies was overwhelmed.’ Anonymous

Most boys seemed to have visited Grubbies around once a week – more if they could afford it, but most could not. As Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46) commented ‘It was usually our pockets, not rationing, that limited our custom at Grubbies.’ He explained that pocket money was deposited with Tutors at the beginning of each term, and ‘only on his authority could it be withdrawn. For this purpose, we concocted fanciful and barely plausible needs. A few were believed.’

‘I was on short pocket money as my dad knew I would just spend it, and I applied the same for my son forty years later.’

Anonymous

Not surprisingly, many OWs could recall the exact amount of their pocket money, and how far it went:

‘Even a few years after the war, ice-creams were a luxury and our weekly pocket money was one shilling! Not much even in those days. My father used to give us ten shillings and that would last a term.’ Bertram Rope (Picton 1949-54)

‘Our one shilling a week pocket money barely covered a single ice-cream. Still, that was a treat. The pocket money limit was rigorously enforced, and with hindsight I feel this was an excellent rule. I had no idea about the financial background of any of my friends and others…’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

‘My parents gave me £20 each term that was deposited at Grubbies, and each time I purchased something a chit was raised to cover payment against my account. £20 on top of the school fees was significant in those days, but I still had to ask my parents for a top up each term.’ Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953-57)

‘I ate mainly ice-cream, pink ones most of the time. I think they cost 4d each. I know my money didn’t stretch as far as I would have wished, and how grateful I was for a ten bob note to swell resources in my first term. My great aunt used to take me out and once gave me half a crown. This was real money, seven ice-creams!’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘My passion was McVities chocolate digestive biscuits – and they still are!! In those days I found it difficult to avoid eating a whole packet in one sitting! Those biscuits were quite expensive – 12½ old pence a pack. As proof of my regularity at Grubbies, I feature in the London Illustrated News article on Wellington in 1958!’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58)

‘For sixpence, you could get a pie and a coke. But the weekly pocket money was only sixpence, so it was a rare but wonderful experience.’

Michael Moore (Lynedoch 1955-60)

Because of the perceived expense, Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52) recalled that ‘there was a custom that you paid for what you ate and did not expect to be treated by a friend.’ Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52) remembered ‘Once, on an unexpectedly hot day, Mr Allen gave the boys 2/6d to buy extra ice-cream.’

The bill of fare

At different times, Grubbies seems to have sold a remarkable variety of foodstuffs, but some were mentioned again and again. During the war, hungry boys bought bread to fill them up:

‘Grubbies kept us going on bread rolls.’ David Simonds (Orange 1941-46)

‘In particular I remember the newly-baked rolls with a Spam filling. Loaves of bread were also available (bread was not rationed till after the war). We used to buy a complete loaf and eat it as we made our way back to College, until this practice was forbidden on the grounds that it gave people a detrimental opinion of the food available in Hall.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

Far and away the most popular treat was ice-cream, mentioned by dozens of our respondents.

‘There were two sorts of ice-cream, pink and white, no mention of actual flavour.’

Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘They did a particularly good form of pink ice-cream, dyed with cochineal it was said.’ Robert Hirst (Picton 1955-59)

‘I spent a lot of time in Grubbies on half day afternoons consuming pink ice-creams in summer.’ Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54)

‘White ice-cream & Pepsi was my standard fare.’ David Ward (Hopetoun 1954-58)

The ice-cream could also be accompanied by fresh raspberries or strawberries when these were in season. It was home-made, by Grubbies manager Nellie Hook, and universally loved:

‘In fact, the Grubbies ice-cream was so special that I never found the equivalent taste anywhere.’ Ross Mallock (Murray 1954-59)

A couple of OWs mentioned coffee ice-cream, and others iced coffee, a surprisingly sophisticated beverage for the 1950s? A couple of the oldest respondents described soft drinks, again only known by their colours:

‘I always remember the sweet drinks – red, white, or yellow, with or without cream.’ Dick Barton (Lynedoch 1938-42)

‘Favourite drink a “twopenny red”.’ John Stitt (Murray 1940-45)

Were these the same as milkshakes?

‘I only bought strawberry milkshakes, usually without milk as it was more expensive … a fourpenny strawberry milkshake, but without any milk in it – milk cost double and could only be afforded on high days and holidays.’ John de Grey (Blücher 1938-43)

By the end of the war, the milkshakes were established and very popular, praised by many respondents. Coffee, Horlicks, and later Coca Cola were also mentioned.

Other foodstuffs singled out in replies were chocolate digestives, malt loaf, flapjacks, doughnuts, Penguins and peanut butter. Sandwiches were also available – cheese were apparently the cheapest, but marmalade sandwiches were also popular. Only one reply mentioned buying crisps.

Some foods became popular for bartering within the dormitories. Sam Osmond (Hill 1946-51) recalled that ‘Mars bars from Grubbies were a form of currency,’ while Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53) wrote: ‘The thing I really looked forward to getting was a small tin of condensed milk that cost sixpence. They were widely popular for their use as a parallel currency throughout the Beresford.’

Chris Heath also recalled the potential hazards of consuming food bought at Grubbies:

‘Cakes and buns, you were allowed to eat within a certain distance of the shop or take back to your room. If you were caught eating while walking elsewhere, you could be in for serious trouble. Once, I was wandering past the squash courts on my way to the village while munching away on a bun. Suddenly I looked up and saw a particularly sadistic Head Boy coming from the other direction. I dodged into the bushes and spat out everything by pretending to be sick. He saw me but let me go as he couldn’t disprove my lies.’

Towards the end of the period, a new item appeared on sale: ‘I specifically recall with fond memory hot pie, introduced during my time, in the winter terms. Interestingly the same brand of hot pie was provided infrequently by the Steward in Hall. Naturally the Hall version was only half a pie per head!’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

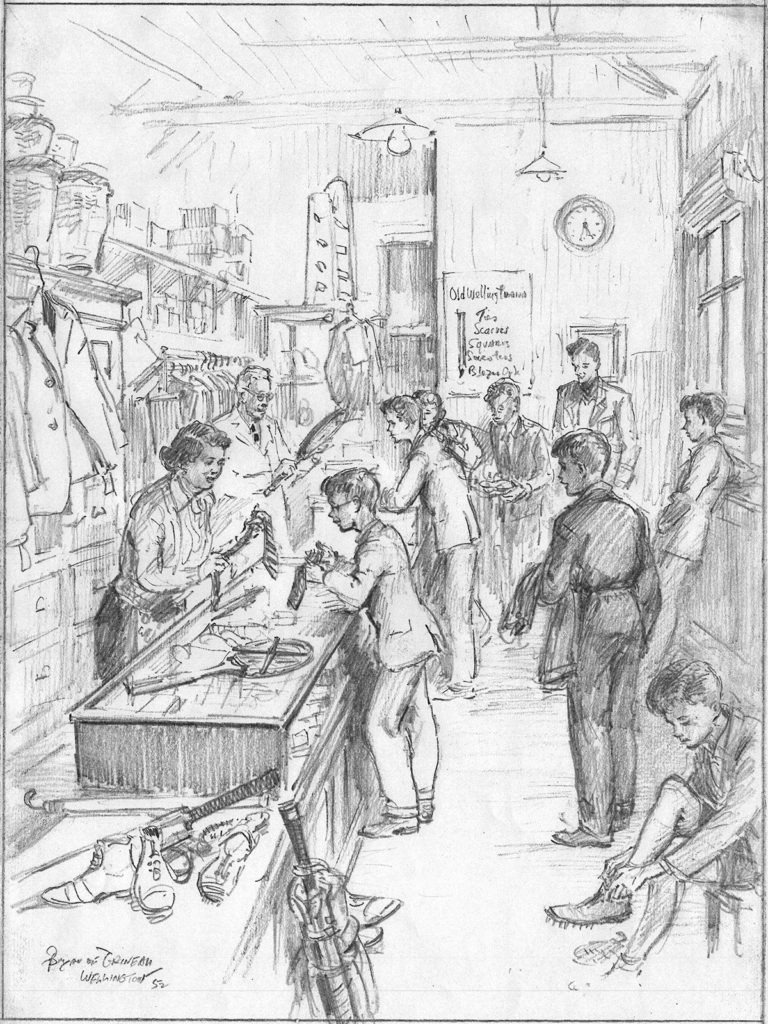

Clothes and accessories

Grubbies also sold clothing: new and second-hand items of uniform, sports kit, and marks of distinction such as ‘Colours’ caps and ties. This was invaluable, as for much of the 1940s and 50s clothing, as well as food, was rationed, but as Richard Craven (Hill 1950-54) explained, ‘this was a great way to cope with growing up, as clothing also required coupons, but second-hand clothing was exempt.’

‘I am reliably informed that one new boy was convinced by his friends to ask the lady assistant for a “jock strap,” believing it to be a rugby scrum cap. When fleecy “windcheaters” were introduced from America, Grubbies were among the first to stock them.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

At the end of one’s Wellington career, ‘when we left College, there was the ritual trip to Grubbies’ drapery section for the mandatory OW ties, scarves, and other bits and pieces.’ Anonymous

‘I bought a set of OW cufflinks when I left (I still have them), the OW tie, and an unusual scarf of the university variety, rather than the long woolly one.’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

‘Grubbies, Arthur and Nellie Hook’s domain… I got to know them well and they very kindly gave me an OW bow tie when I left. They knew, of course, that, being in the Talbot, I would know how it was tied.’

John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

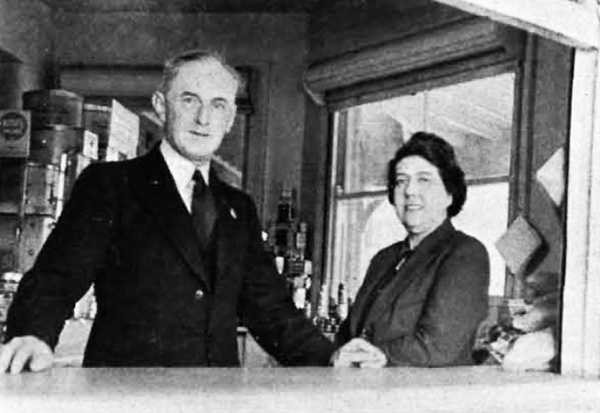

Arthur and Nellie Hook

Arthur Hook took over Grubbies from his father in 1923, and with his wife Nellie, ran it until 1961. They and their staff were remembered fondly by many of our respondents:

‘Throughout my time, Grubbies was managed by Arthur and Nellie Hook. It seemed that they had been there for ever, and were greatly respected not only by the boys, but also by parents when needing assistance and advice whilst purchasing clothing.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

‘Grubbies was marvellous, run by such a friendly lady.’ ‘Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

‘Charming people running it…’ David Simonds (Orange 1941-46)

‘The staff were remarkable, kind and helpful.’ William Young (Anglesey 1954-58)

‘The staff as I remember were kindly middle-aged ladies who found us amusing.’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

‘The Grubbies staff were invariably cheerful and courteous in their dealings with us, a feral, hungry mob.’

Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

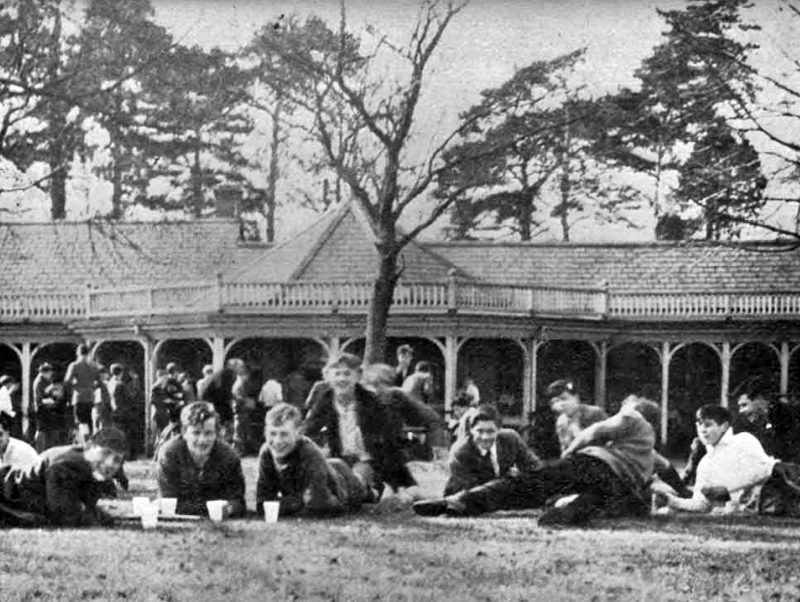

A place to relax

The atmosphere and social opportunities which Grubbies provided seem to have been appreciated almost as much as the food. One pastime in particular was remembered fondly:

‘It was lovely to sit outside and watch the cricket matches on that beautiful ground.’ Anonymous

‘A special memory is buying bags of cherries in the summer and lying on the grass eating them, while watching the First XI playing on Turf.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘One of the sybaritic pleasures of my time at Wellington was being with friends, buying a delicious strawberry ice-cream and stretching out on the grass adjacent to Grubbies to enjoy First XI cricket (in one’s memory it always seemed to be sunny!)’ Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951-55)

Although occasionally there was an upset: ‘One summer day there was a memorable event at Grubbies. We had an American exchange student called Stemple who was a sturdy, athletic baseball player. He was being introduced to the art of batting in the cricket nets and no matter how earnestly he was entreated not to hold the bat cocked over his shoulder as in baseball, he insisted. The ball was bowled, he gave it a mighty whack and it flew out of the nets towards the roof of Grubbies where it crashed through a skylight onto and through the glass of the display case beneath. We told him from then on, he should hold the bat however he wished.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

Likewise, in the winter, ‘there was a room, akin to a conservatory, adjoining Grubbies in which one could sit at tables to eat and drink in a civilised fashion out of the elements’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61).

‘It was quite a gathering point after games and welcome protection from the weather on many a cold, wet afternoon.’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

‘After team matches, the visitors and home teams would usually have a tea together in the adjacent dining room.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

In those days, Grubbies provided one of the few places where boys from different dormitories and houses could mingle freely, and this was much appreciated and seen as a rare slice of ‘normal life’:

‘I recall it as a sanctuary and a wonderful distraction from the routine of college life. Since we were confined to college grounds for the first three years, Grubbies was the nearest thing to experiencing the outside world.’ Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60)

‘Everybody must have good memories of Grubbies, the only place in the College that would remind you of the outside world.’ Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53)

And several clearly felt that it had been a contributor to what we might now call ‘well-being’:

‘The atmosphere was an escape from the heavy feel of College.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55)

‘Grubbies was a godsend. However badly life seemed to be treating you, a visit to Grubbies would aIways provide a lift.’ John Watson (Benson 1946-51)

‘Grubbies was a life-saver. After afternoon sport, an ice-cream cone would set the whole world to rights, accompanied by a Coke.’

Ross Mallock (Murray 1954-59)