Teachers: English and History

In the mid-20th century it was common for teachers, particularly on the Arts side, to teach several subjects. Thus, though we have tried to group them by their specialism, many respondents may remember the same ushers teaching them English, History, Philosophy, or even languages.

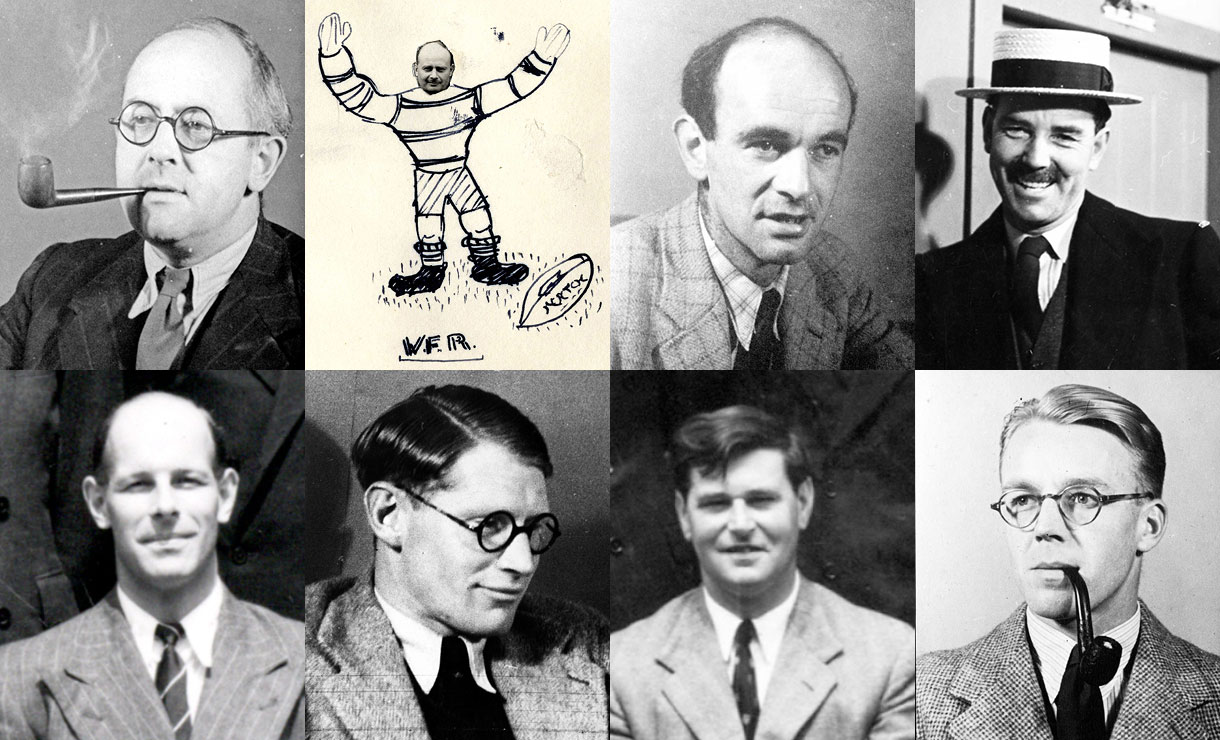

Some of these polymaths were definitely larger than life, for example John ‘Jim’ Crow, remembered vividly by those who were here in the 1940s:

‘There was also Jim Crow, who taught us History, and was so extremely corpulent that he needed a special outsize bicycle saddle to accommodate his posterior. Sometimes he sat at his desk with a halo chalked on the blackboard behind him, leaning back in his big chair so that the halo exactly fitted him. He had a fearsome instrument, a kind of pick helve, which he kept by him and crashed down on the desk beside any inattentive pupil, shouting “You boy!”’ Peter Bell (Blücher 1943-48)

‘…the outrageous Mr Crow, a round figure dressed in shirts that we thought were made from café tablecloths.’

Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘Jim Crow, supposedly the greatest authority on Christopher Marlowe. He had a habit of sending postcards to his academic and literary friends containing acerbic comments on contemporary celebrities. I even remember one:

Where are you going, you little mouse?

I’m off to church to worship Rowse [A L Rowse, a rather publicity-hunting historian]

Don’t be silly, you little elf,

He’s taken on the job himself.’

Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47) remembered a rather less high-brow poem, presented to an unidentified English teacher:

‘On one occasion, I did one prep but completely forgot about the other one. It was only when the prep – which turned out to be writing a poem – was being collected at the end of a lesson two days later that I realised my ghastly mistake. The English master expected his preps to be completed with absolutely no excuses – I was terrified and hurriedly scribbled the first thing that came into my head, which was:

What means this gory mess?

‘Tis Fido more or less,

While crossing the road

In chase of a toad,

A car ran over his corpus.

You can imagine how surprised and greatly relieved I was when at the next English lesson, the master read my poem out as one of the three he liked best!’

Some were also respected for their skill as Form Masters. One such was Fergus Russell, described thus in his leaving tribute in the 1968 Year Book:

‘During all his years at College, it was his lot — and he with characteristic modesty regarded it as a privilege — to teach the form which once was known as the Lower Fourth. Generations of boys — not, on their arrival at Wellington, the most forward with their studies — found in him the same sympathy and patience, the same good humour and kindness, the same well-stored mind. For Fergus Russell was the archetypal Form Master, a genus which at one time seemed doomed to extinction, though now set for a new lease of life. He taught English, History, French and, for a time, Latin.’

He was similarly remembered by our respondents:

‘Fergie Russell was a classic schoolmaster, down to earth and positive.’

Tim Shoosmith (Blücher 1953-57)

‘I began my career in the Upper Fourth, with Fergie Russell as my Form Master. Fergie was fun, a good teacher, and with the habit of hunching himself down in his gown that I shall never forget.’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

English

English was a subject studied by all Wellingtonians. Depending on the skill of the teacher, and the interest of the pupil, English lessons could be either a trial to be endured, or the inspiration for a life-long love of literature.

One of our older respondents, Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941-45), considered that ‘Robin Gordon Walker was an inspirational teacher of English literature in the run-up to the School Certificate,’ and John Stitt (Murray 1940-45) also considered him ‘very special.’ However, his near contemporary, Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46), found lessons with another teacher memorable for a different reason:

‘To Mr Manby for English. We had frequently brought to his attention the presence of a large (mythical) rat that often appeared from a hole by the radiator. He showed no interest, so we planned a punitive action. At an agreed moment during a class, “the rat” was seen and at my command, “Eh, there ‘e is, the bugger,” most of us threw our books at the corner where so cheekily sat the rodent. Of course, we failed to produce a corpse, and indeed the sincerity of our endeavour was brought into question when three boys cast their literary missiles into different corners of the room.’

One teacher remembered by a great many OWs was the ‘delightful eccentric,’ Anthony Sebastian Crawley, known to all by his full name.

He was well-known for ‘possibly the most beautiful speaking voice of anyone personally known to me; to hear him read the lesson in Chapel was an absolute joy!’ according to Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951-55). Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58) described this as: ‘the most extreme of old-fashioned Oxford accents. “Anthony Sebastian Crawley.” Try saying that whilst yawning and trying to take chewing gum off your teeth with your tongue at the same time and you will probably get quite close.’

Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55) describes Crawley as ‘A tall, languid figure, a bachelor, had a vintage Rolls-Royce. Taught English, kept me interested.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56) outlines a few more of his eccentricities:

‘Time in the First Block brought me under the wing of Anthony Sebastian Crawley, one of those who got by without going the extra mile. He had an obsession about how to treat books, taking care not to break the spine. He was also the man who first made me aware of looking to see the date on which a book was published and whether one was reading the first or the umpteenth edition. Most publishers provide this information, but there was one who never fulfilled their obligations to the satisfaction of ASC. I can see him now dismissing a whole book because of what it said about itself in the introductory pages. “Cassells again!” he said, snapping the book shut, his unforgiving verdict on the publisher confirmed.

One was required to ‘tick’ all staff on passing them in the quads. Some always acknowledged, some never, but with Crawley one always had the prospect of hearing him say “Heigh ho!”’

Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55) reported ‘I had no time for, or empathy with, Anthony Sebastian Crawley and must have been the only boy who failed English Literature.’ Others, however, had better memories:

‘Anthony Sebastian Crawley, unforgettably, took me through O Level English Literature with the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales: “Wan that Aprile with his showres soote…”’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘Mr Crawley (“Anthony Sebastian,” spoken very drawlingly), introduced us to grown-up English, through the medium of The Spectator. For English Literature in the School Cert we had ‘done’ Paradise Lost and Hamlet. Well, Hamlet is not exactly modern, and Paradise Lost certainly isn’t, and while I’d read a bit of Arthur Bryant for history, my modern reading was virtually non-existent, though I was starting to read grown-up novels. So The Spectator got our minds starting to tick over – both in language and politics.’ Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948-1950)

Other teachers were also remembered for incorporating literature beyond the scope of the syllabus:

‘In Upper 3A I flourished a little under “Tubby” Aglen, who introduced me to HH Munroe’s Saki stories. Although about twelve years ago I found in a file 100 lines written out in my fairy hand of James Ch 3 v 8 “but the tongue can no man tame, it is an unruly evil…” etc., which fitted on two lines of foolscap and was standard punishment meted out by Tubby for talking in a lesson. I must have had a good four or five of these and obviously did not hand this lot in, on the basis I would probably get another one again.’ Anonymous

‘My favourite subject was English Lit, very well taught especially by “Dip” Pearce, who not only got us interested in the set texts but expanded our interests way beyond them. We read Hay Fever in class while studying Julius Caesar!’ John Armstrong-MacDonnell (Talbot 1952-56)

Several OWs remembered learning poetry by heart:

‘Dougie Young taught me English and French; I can still recite Adelstrop.’ Bryan Stevens (Blücher 1948-52)

‘In the Third Form, the master offered half a crown (or five shillings, I forget which) to any boy who could learn Robert Browning’s 140-line Hervé Riel poem by heart, and I was the only one who got the money.’ Hugh Trevor (Hopetoun 1943-48)

Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60) enjoyed a different aspect of the subject: ‘I enjoyed English Literature, especially Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Middle English had an appeal in that you could get just enough of an idea to be lured into learning Middle English terms to complete one’s understanding of the text. The tales were also intriguing. I think it was well taught.’

One popular teacher was Peter Comber, described by Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56) as ‘a typical example of a Wellington teacher who had served in the War. He had been a Chindit and served under Orde Wingate in Burma, fighting behind the lines and harassing the Japanese. He must have experienced an unbelievably savage war, but never spoke of it. He sought solace in Christianity. He was a kind man and popular with the boys.’ Neil Munro (Talbot 1952-56) also remembered him:

‘Peter Comber, an unassuming man who devoted much of a term in English to those two splendid Milton poems, L’Allegro and Il Penseroso, favourites ever since. I am something of a Hamlet freak, often taking a pocket edition with me wherever I go. This I attribute to a term with “Dog” Baker, not widely seen as particularly inspirational, but who by dint of making us act out the play in class, unlocked its extraordinary universality for me.’

These Milton poems must have been a staple of the syllabus, as others had less fond memories of them:

‘I recall the dullest lessons of my five years involved Philip Letts taking most of a term to drag us through Il Penseroso and L’Allegro… He managed to quash any lingering love of English poetry by dissecting them to a depth that I feel sure Milton never intended, before finding he barely had time for Lycidas. How far he was from leaving me with a yearning to read more.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

However, Peter Marshall (Stanley 1947-51) had a better opinion of Mr Letts:

‘I have vivid memories of being taught Hamlet and Paradise Lost in a brisk and wholly realistic way by Philip Letts for School Certificate English. These books were beyond our capacity to comprehend and no doubt beyond his to expound to any depth, but he made us learn passages by heart in a jolly non-coercive way, helped us at least to follow the plot of Hamlet and to understand Milton’s cosmology by drawing maps of heaven and hell to illustrate the passage of the rebel angels, who fell “thick as autumnal leaves that strow the brooks of Vallombrosa.” At a more sophisticated level, I do remember some wonderful classes about poetry taught by, I think, Alan Ker, who later taught Classics at Cambridge. These fired in me an adolescent passion for Keats and Tennyson.’

One popular teacher was Mr Annand:

‘The best course I took was Romantic poetry from Mr. Annand.’ Tim Travers (Hopetoun 1952-56)

‘Annand was a nice man, who tried to teach me Ancient History and who once wrote memorably of one of my efforts: “This is more like a bird’s nest than an essay.”’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘Mr Annand introduced us to ‘proper’ poetry. Before that my knowledge of poetry was confined to One Hundred Best Poems for Boys, which was mostly Henry Newbolt and his ilk – “Drake he’s in his hammock, and a thousand miles away – Cap’n, art thou sleeping there below…” Now we were introduced to Browning, in particular his conversation pieces, Fra Lippo Lippi, My Last Duchess and Bishop Blougram’s Apology, as well as his more lyrical verse.’ Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948-1950)

Although one anonymous OW had a different memory:

‘Our English master, Annand, was very serious and seemingly without much humour. His desk was on a dais. Just before he entered, I placed his desk right on the very edge so that the slightest movement by him would send it crashing down. Unfortunately, in hurrying to get back to my desk I just clipped the platform with my heel. He was certainly not amused to see his desk cartwheel in front of his eyes, spilling his books all over the place. I owned up when asked and received six of the best from his cane.’

Graham ‘Chalky’ Meikle, so nicknamed because he was reputed to put a piece of chalk in the tip of his cane for delivering accurate strokes, was clearly not to be messed with, but was much liked and respected as a teacher:

‘I loved English Literature, taught by Graham Meikle, who was inspiring in the most unassuming way.’ ‘Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

‘Mr Meikle, involved with Athletics, was a thoroughly decent person, one of the staff with whom one could talk freely and openly.’

Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘The other one who stands out was Graham Meikle (GWCM). I found that I responded to his teaching very well.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

And Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59) sent in this very moving recollection:

‘Another winner was Mr. Meikle teaching English. He recognised my shyness and told me how he had overcome his own shyness. When he lived in London, a relative taught him to talk to the person sitting next to him on the bus every day. It was agonizingly difficult at first, but after a few weeks it became enjoyable as he met all kinds of interesting and funny strangers.

One day I failed to finish an essay on time, so he told me I had to finish it by next day and had to read it out loud to the class. The subject was to recall a childhood memory and I described how, as a five-year-old with the little boy next door, we created an imaginary pirate ship amongst the branches of a big old pine tree. When I had finished reading it, there was an awkwardly long silence as Mr. Meikle slowly removed his glasses. Then we realized that Mr. Meikle was in tears.’

History

Most of those who commented on their History lessons at Wellington seem to have enjoyed them, although Nick Harding (Combermere) 1951-1955 observed that in those days, ‘History stopped something like mid-19th century with no attempt made to join it up with current life.’

Several teachers were remembered with great respect and affection, among them the Head of History in the 1940s, Mr Reese:

‘Mr Reese, our senior History teacher, would perch, knees up, in the window recess in his classroom, instead of sitting at his desk. On entering, there would be a pause while he climbed up.’ John de Grey (Blücher 1938-43)

‘Under the brilliant – even genius – teaching of Max “Gaffer” Reese I got a place at Oxford through the History scholarship exam.’

John Stitt (Murray 1940-45)

‘I was encouraged to go onto the History Side by Max Reese who had remarkable success in gaining Oxbridge scholarships for his pupils – a process of turning geese into swans. He threw back all our first essays as “Boring! A good essay should always start with an arresting first sentence – read Bacon’s Essays. Try to make your essays interesting, maybe unusual.”’ Sam Osmond (Hill 1946-51)

‘Max Reese influenced me and the whole History Side. He taught entirely from his own book on the Tudors and Stuarts, and assumed all his pupils would go to Oxbridge. He disdained Higher School Certificate (A Levels). This left some pupils high and dry.’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘I was briefly exposed to the magic of “Gaffer” Reese. His understanding, enthusiasm and interest in me struck me as extraordinary and had an immediate effect on my views about learning. I longed to be taught by him again – but I was not.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

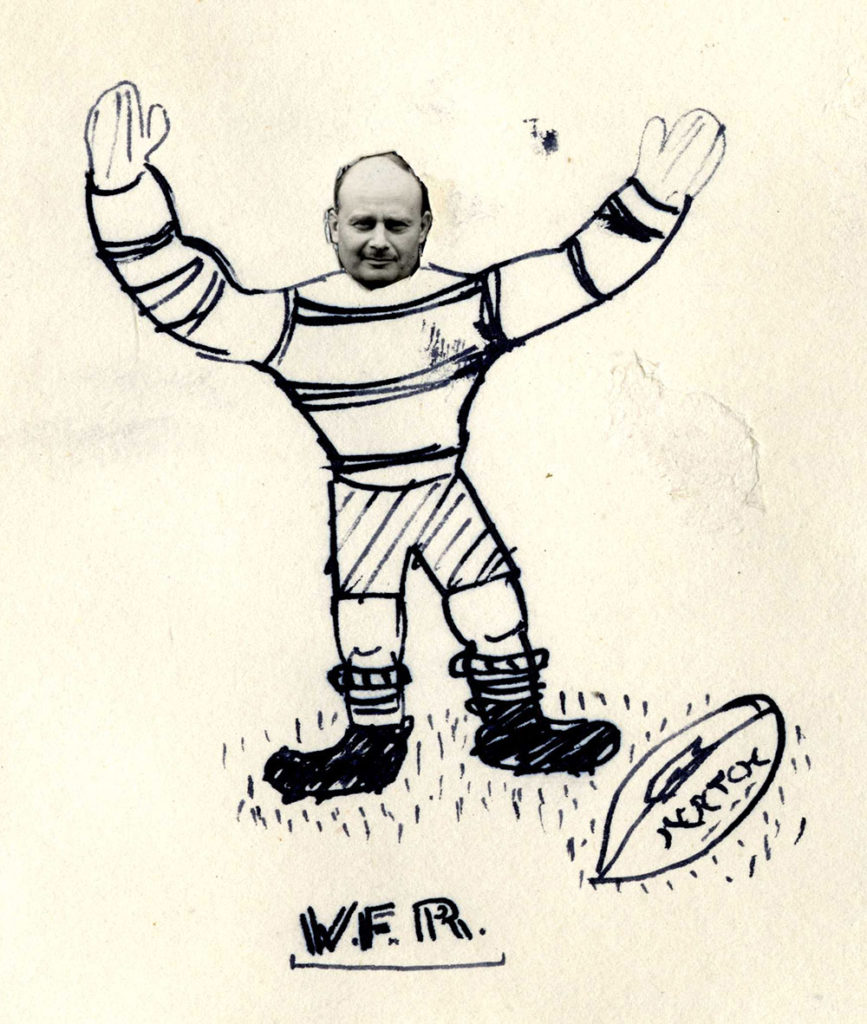

Peter Firth (Hardinge 1941-46) attributed his exhibition at Merton College, Oxford to Max Reese and also to Raymond Carr, both excellent teachers. Others also remembered Carr:

‘Raymond Carr, an authority on Spanish history. He impressed us boys with his repertoire of blue stories and an array of glamorous visitors at weekends. Later he became Sir Raymond Carr, first Principal of St Anthony’s College Oxford.’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘Raymond Carr, only a few years older than us, but with a double First in European History… He had not been called up to fight, because his health was such that he was not expected to live long. He made no concessions to Wellington and behaved as a free agent. He would sometimes take us up to his rooms and play the clarinet instead of doing history. But when he did do it, he kept us up to the mark with arguments and facts to deploy for the scholarship exam.’ John de Grey (Blücher 1938-43)

Others mentioned Mr Kuper:

‘Charlie Kuper was my favourite teacher as he was friendly and taught History in a way that made it really come alive.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954-57)

‘Kuper painted sumptuous pictures with words in describing battles.’ David Nalder (Orange 1949-53)

A History teacher singled out by many as inspirational was Christopher Bulteel, whose career at Wellington was summarised by Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59):

‘He had been a boy at Wellington himself before the Second World War, had joined the Coldstream Guards and won an MC at Salerno. He returned in 1948 to Wellington to teach History before becoming, for a short time, an Anglican Franciscan friar at Cerne Abbas in Dorset. He spent most of the 50s at Wellington teaching History… He didn’t so much lecture, as gently lead his students towards wanting to learn about the subject for themselves. He had a particular gift for introducing us to books which proved the means of unlocking fresh fields of knowledge.’

Many more felt similarly:

‘Bulteel was mesmeric and invariably finished his lessons with a chapter from James Thurber’s Thurber Carnival.’

David Nalder (Orange 1949-53)

‘The greatest influence was undoubtedly Christopher Bulteel, who taught us History. There were about eight of us who rebelled against the military ethos of the school, and we were all inspired by Chris’s brilliant teaching and general influence on us.’ Bryan Stevens (Blücher 1948-52)

‘He inspired one to wish to know more, he took us on expeditions to places of historic interest and above all he introduced us to tutorial style learning by often taking the (small) class in his sitting room in the Long Corridor.’ John Watson (Benson 1946-51)

‘I owe a great deal to him. He taught us mostly like an Oxford or Cambridge don in his own room. He treated us like adult undergraduates and encouraged us to read for ourselves. I felt that I was in the presence of a real intellectual and scholar.’ Peter Marshall (Stanley 1947-51)

Others expressed appreciation for Bulteel’s pastoral qualities:

‘Chris Bulteel was the most influential and interesting member of the teaching staff I came across, but his part was more pastoral than academic for me.’ William Young (Anglesey 1954-58)

‘I have always considered myself truly fortunate to have been allocated in my first term Chris Bulteel as my form master. He was an OW himself, and future headmaster of Ardingly College. His previous experiences as a wartime Coldstream Guards officer, and later monk, may have contributed, but basically he was an ideal schoolmaster, with the perfect temperament, who knew how to settle boys in their first term as boarders.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

The other History (and English) teacher who inspired many during the 1950s was David Newsome:

‘Early release from scientific subjects was very welcome, thereafter my favourite subject was History, as a matter of genuine interest, which was supported by Dr David Newsome, who was positive and engaging.’ Hardy Stroud (Combermere 1950-55)

‘I specialised in History after O Level, and have particularly warm memories of David Newsome. He was an inspirational teacher.’ Anonymous

‘Outside the Classics, the greatest impression was made by David Newsome in the period before he became Master; he taught English with flair and a genuine interest in our efforts.’

Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952-57)

‘The History Side was particularly strong during my time at Wellington. Its head was David Newsome, a nineteenth-century ecclesiastical historian, who divided his career between schoolmastering at Wellington and university lecturing at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. My contemporaries and I found him an inspirational teacher, who treated us like university undergraduates. He would spend the majority of class time lecturing, when he expected us to take notes, and would then invite two of us at a time to his house to discuss our weekly essays. His lectures on the Crusades, the Renaissance and the Reformation were especially memorable. He succeeded in giving us a real passion for our subject.’ Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

‘In the History VIth, teaching was in the hands of two inspirational tutors, Chris Bulteel and David Newsome, both of whom gave me a long-lasting love of the subject, and a determination also to become a teacher.’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

‘The most inspiring periods in the classroom were sitting at the foot of the young Newsome. He would parade up and down the room twirling his gown in his right hand with his left foot splayed out as he strode. Years later, when he was Master, I asked him if he still strode around in this very distinctive manner. He claimed no awareness of the characteristic at all, but in addressing us later he made reference to the dangers of meeting those he had taught in his youth and their ability to recall his idiosyncrasies! Newsome believed I could write, and he encouraged me to do so.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

A sample report

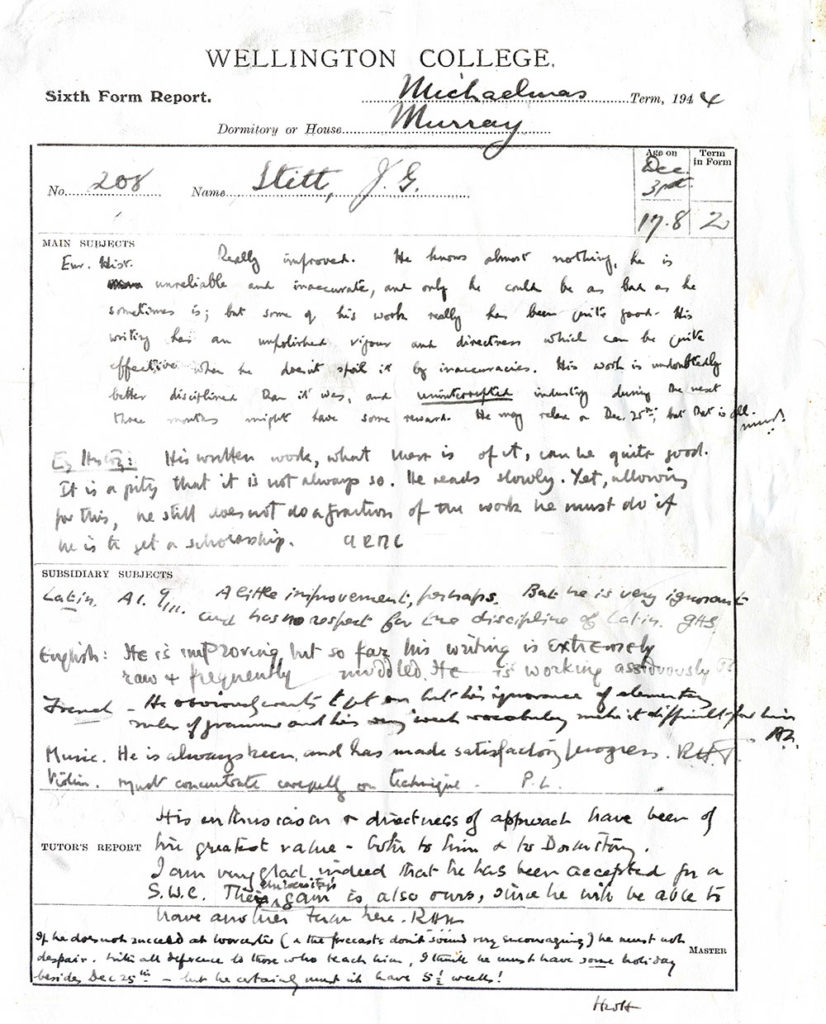

Many of the teachers mentioned above contributed to the termly report sent in by John Stitt (Murray 1940-45).

Their comments, which certainly give a flavour of the characters concerned, include the following:

‘Gaffer’ Reese on European History: ‘Really improved. He knows almost nothing, he is unreliable and inaccurate, and only he could be as bad as he sometimes is; but some of his work really has been quite good. His writing has an unpolished vigour and directness which can be quite effective when he does not spoil it by inaccuracies. His work is undoubtedly better than it was, and uninterrupted industry during the next three months might have some reward. He may relax on Dec. 25th, but that is all.’

Raymond Carr on English History: ‘His written work, what there is of it, can be quite good. It is a pity that it is not always so. He reads slowly. Yet, allowing for this, he still does not do a fraction of the work he must do if he is to get a scholarship.’

Graham Stainforth, later Master of Wellington, on Latin: ‘A little improvement; perhaps. But he is very ignorant and has no respect for the discipline of Latin.’

John Crow, on English: ‘He is improving, but so far his writing is extremely raw and frequently muddled. He is working assiduously.’

French: ‘He obviously wants to get on, but his ignorance of elementary rules of grammar and his very weak vocabulary make it difficult for him.’

The Tutor of the Murray (of which John was then Head), Rupert Horsley: ‘His enthusiasm and directness of approach have been of the greatest value – both to him and to Dormitory. I am very glad indeed that he has been accepted for a SWC [Scholarship of Worcester College]. The university’s gain is also ours, since he will be able to have another term here.’

Harry House, the Master: ‘If he does not succeed at Worcester (and the forecasts don’t sound very encouraging) he must not despair. With all deference to those who teach him, I think he must have some holiday besides Dec 25th, but he certainly must not have 5½ weeks!’

John tells us that in the end, he failed to achieve the scholarship at Worcester, but was accepted by Oriel College as a Commoner as a result of having taken their History scholarship exam.