The War and its Legacy

For our earliest participants, the Second World War was a very real and immediate part of their Wellington College experience. Even when it was over, the War had a considerable impact on school life throughout the 1940s and 1950s; food rationing continued until 1954, and ‘landwork’ by boys for even longer.

Preparing for war

Our oldest respondents remembered the preparations for the War, when air raid shelters were constructed:

‘We dug out the Blücher air raid shelter, as a biweekly “change,” for months…’ John de Grey (Blücher 1938-43)

‘One memory of my first term is of the whole dormitory turning out to dig the vast pit for the Combermere’s air raid shelter. The Munich crisis had only recently passed and precautions were being taken. We dug the hole – at a guess 60 x 40 x 10 feet deep. It was hard yellow sand, pick-and-shovel work. This was just on the north side of what were then the ushers’ garages, off to the left from the road to the gym. Once dug, we forgot about it for a year or so.’ Robert Longmore (Combermere 1938-43)

Other measures were also put in place:

‘Glass ceilings (e.g. in lavatories) were painted blue, and light bulbs red, which satisfied blackout requirements. Blackout curtains in our cubicles were checked every evening and taken very seriously.’ Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47)

‘Respirators or gas masks had to be carried at all times away from the College buildings. ARP (Air Raid Precautions) and the Home Guard affected many of the senior boys.’ Jock Brazier (Hill 1941-45)

‘A watch was kept in one of the towers when air raids were forecast. I do remember that lonely vigil.’

Anonymous

‘At night, the Armoury held a posse of boys from the JTC (Junior Training Corps), with rifles but no ammunition, at immediate readiness to dash out and confront any German parachutists spotted in the area. One boy at a time was also stationed at the top of the ornamental turret above the Blücher dormitory, made accessible by means of a wooden ladder. The ornamental white acorn-lidded blister at the top was just big enough to hold a seat with a small shelf in front, with a panorama of the surrounding territory with place names on stalks, painted by the Art Master. It was very well done, and must have taken quite a bit of his valuable time. The field telephone in the turret was connected to the Armoury, where the gallant JTC reinforcements were closeted, and you reported a successful change of observers when you got up there (2 hours on duty) after shouting up to call the previous guard down. Comically, the field telephone line laid above ground survived when the underground one from the ARP Headquarters to the Armoury was blown up. It had gone round the other side of the brick gatepost.’ John de Grey (Blücher 1938-43)

‘I found myself in charge of the ARP Section. We inhabited a shelter under one of the Science blocks, the entrance to which led out onto the short drive running from the kitchens down to the Kilometre. We were equipped with dark blue boiler suits (I had yellow sergeant’s stripes) and blue tin hats, and did fire and first aid drill.’ Robert Longmore (Combermere 1938-43)

‘I was asked to join the Auxiliary Fire Service and operate a trailer pump. This was marvellous, because members of the team had to have a bicycle so that they could quickly man the pump.’ Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941-45)

Life in the shelters

From the summer of 1940 onwards, the air raid shelters were in regular use:

‘Whenever the air raid sirens blew, we had to traipse off to air raid shelters dotted across College, and spend the night on lilos.’ Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘In an orderly fashion and thick sweaters, we trooped down, clasping our blankets and inflatable lilos, and remained on our wooden slatted bunks till dawn.’

Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

These lilos and their shortcomings were mentioned by many OWs. Robert Longmore (Combermere 1938-43) explained:

‘The shelters had been fitted out with bunks, each with a lilo for us to sleep on. Unfortunately, the carpentry had obviously been done in a hurry and none of the wood had been planed. Lilos and un-planed wood did not go well together, and the hiss of escaping air when punctured by splinters was frequent!’

‘We were handed a lilo each… unfortunately I was the last in the queue and mine had a puncture, so my first night I slept on a flat lilo on duck boards!’ Jock Brazier (Hill 1941-45)

‘I well remember the sound of the hiss of air, followed by a stream of abuse as some poor soul’s lilo deflated.’

Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

John de Grey (Blücher 1938-43) recalled the humorous side of shelter life:

‘A retired Chemistry master had been rounded up to sleep there and maintain discipline. He must have been over sixty-five, which to us boys was impossibly old. His voice had lost some of its vigour, so his nickname was soon “Rusty Balls.” I don’t think he ever found out. We were quite good at preserving our confidentialities, but every night every boy was enjoying the joke each time he spoke.

Boys needing to relieve themselves during the night (most of them) would go out to the edge of the wood, so we planned to pick a single tree and see if we could kill it with salt. And we could. I think it took about six months.’

The bombing of College

Several OWs remembered the fateful night of 8 October 1940, when bombs dropped on College.

‘I was in the Upcott air raid shelter when the bomb fell which killed Bobby Longden, and can whistle the very noise it made as it fell.’

John Stitt (Murray 1940-45)

‘On the night that the bombs actually fell, I remember a boy member of the ARP Unit poking his nose into our shelter and asking whether the Master was with us; the answer was of course “No.” We heard no more that night, but the next morning the school was addressed by Mr Gould and given the sad news of the Master’s death at the Lodge.’ Robert Longmore (Combermere 1938-43)

‘When the bombs fell, the ARP HQ rang their fellow nighthawks in the Armoury, probably for reassurance that someone was left alive – and could get no answer. They decided to send a boy out on his bicycle to re-establish communication with the Armoury… He had a torch, but did not switch it on as he cycled along, for fear of giving his position away to the enemy! As he cycled through Combermere Quad, all the busts of generals had been sucked out their niches by the blast and were scattered around the quad. When he rode into one, he switched on and thought it was a body, and in the dim light there appeared to be many. Dauntless, he rode on, and found the JTC contingent in good spirits and enjoying an extra mug of Bovril each, to steady them.’ John de Grey (Blücher 1938-43)

‘We were in the shelter one night when we heard the bomb explode. In the morning we were told that our headmaster had been killed. This was a horrid killing. Mr Longden was so young and respected. The bomb damage was evident on the surrounding walls and boys could be seen collecting bits of metal. It was a sombre moment at College but life went on.’ Anonymous

After the Master’s death, the boys spent every night in the air raid shelter for the next year, whether or not the siren had sounded.

Robert Longmore (Combermere 1938-43) remembered ‘an obligatory cold bath every morning. If this was meant to clean us after a night in the shelter, I cannot believe that it did so, as we all fifty-odd of us went in and out of the same two baths without a change of water!’

By October 1941 the threat of bombing had receded, and boys only went to the shelters when the alarm sounded. Nevertheless, this could still result in disruption, especially when the V1 and V2 rockets came into use. Peter Bell (Blücher 1943-48) wrote home in October 1943:

‘We are having lots more air raids recently. On Thursday night we had an awful time. At about 9 o’clock we were just starting second prep when the College siren sounded, so we collected our blankets and bundled down to the shelter outside. There we blew up our lilos, made up the best beds that we could under the circumstances, and we were just getting to sleep when the “all clear” went. So we got up again, it was now about 10 o’clock, and tramped back to College. There we made up our beds again and were just feeling nice and cosy, and that after all it was worthwhile having come up from the shelter, when what should we hear outside but the siren again! So once more we went down to the shelter, made our beds, and the end of it was that we spent a thoroughly cold and uncomfortable night there. ‘

Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48) also recalled ‘getting little sleep. This was particularly irksome during the doodlebug (V1 rocket) offensive in 1944 as they did not come over in regular waves.’ Eventually the threat receded, and John Flinn (Combermere 1944-49) wrote: ‘I recall going to the shelters only once.’

Cultural impact

What impact did the War have on the mindset of Wellington students? Although it was little talked about, all must have been aware that theirs and others’ lives could be cut short.

Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47) came to this realisation in a striking way:

‘My journey out to Canada had involved the sinking of our accompanying ship, the Arandora Star, and on the return journey I learned a lot from the British merchant seamen who had been rescued by the ship on which I was travelling. This, in addition to having seen for myself the tremendous damage caused by torpedoes when a British cruiser with much of its stern missing limped into Ponta Delgada in the Azores, followed by a destroyer with a dangerously steep list and a huge gaping hole in its port bow. It was a very sobering sight… Only a few days later, shortly after returning to England, I was shaken to hear that the well-known actor Leslie Howard had died, because I could have been on the same flight as him.’

Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48) wrote that ‘Our fathers and elder brothers were all in uniform, mostly serving as officers in the fighting arms. News of deaths was not uncommon,’ and yet, ‘the most remarkable thing about our wartime experiences is how we accepted them as being quite normal.’ Likewise David Simonds (Orange 1941-46) had two elder brothers, Guy and Pat, serving during his time at College. Guy was killed while flying with the RAF in 1943. Nevertheless, David wrote, ‘We did what we could, and did not complain.’

Even after the War, students were aware of this legacy of sacrifice, largely due to the physical reminders present:

‘The Chapel had plain windows on the South side where the bomb had landed, killing the Master in his Lodge.’ Ian Nason (Orange 1950-54)

‘The aftermath of war, even though it had ended five years previously, was always in our minds… The Longden Memorial Gate was a constant reminder of tragedies and horrors.’

John Le Mare (Stanley 1950-55)

‘When I arrived at College, the new boys that term (around sixty) were taken round the Chapel by the Chaplain who, pausing before the memorial to those killed in the Wars, informed us that these amounted to about one in six of the former pupils. Inevitably I could not help wondering which ten of us would join their numbers.’ William Field (Lynedoch 1952-56)

Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52) highlighted the greatest impact of all, noting that ‘the War had other effects on boys who had lost a parent.’ The experiences of Foundationers and their contemporaries will be explored elsewhere in this project. However, for those not personally affected in that way, the impact soon faded. Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56) wrote that ‘Apart from the small WW2 comics constantly circulating, I do not recall any special reactions to the War. Although most of our parents had been in the Services, they just had not passed on any of their experiences.’

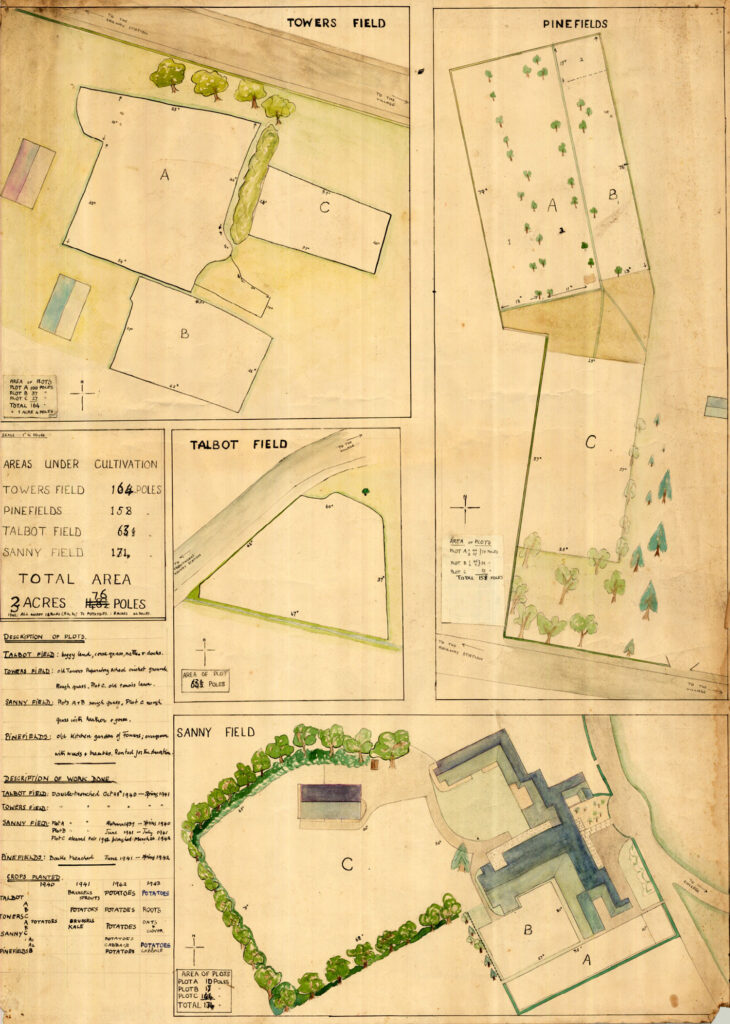

Landwork and other service

During the War, the whole country was encouraged to ‘Dig For Britain,’ and Wellington was no exception. The College already had its own farm, and more land was soon pressed into service: around the old ‘Towers’ preparatory school, near the Talbot, behind Grubbies and the Sanatorium, and elsewhere. By cultivating these areas, the College was able to supply much of its own need for vegetables.

Robert Longmore (Combermere 1938-43) wrote:

‘My first recollection is of an afternoon spent digging potatoes in a small field opposite the entrance to Eagle House. I also remember being taught to use a scythe by the head gardener, who was skilled enough to mow a lawn with it. I learnt to sharpen my scythe properly, with a stone. Bicycling past Turf one day with scythe over my shoulder – unwise perhaps – I came to a stop and watched the blade come gently down to touch my left forearm. I carried the scar of the clean one-inch cut for several years!

Later I became Prefect in Charge of Landwork. I remember riding round on a bicycle, attempting to organise Dormitory work parties. The enclosed kitchen garden on the north-west side of Grubbies was the scene of our main activity, and considerable quantities of vegetables were grown. I do remember that I was quite unable to instill any discipline on my Combermere work party, being met with cheerful ribaldry if I ventured to comment on their efforts at double digging!’

Agricultural work was not confined to the College or to termtime. For several summers, Wellington students helped out on farming or forestry camps during the summer holidays:

‘I went on a forestry camp. We felled trees and then cut them into lengths for pit props. We lived under canvas, took sandwiches for lunch, and fed very well at supper. Occasionally we had campfire singing led by Bertie Kemp.’ Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941-45)

‘Every summer holiday we had to go to harvest camps for a fortnight. Wellington ran three of these camps, one in Scotland and two in England. The Ministry of Transport provided free railway warrants from your home to the camp of your choice. Accommodation was provided by the farmers in their barns. The pay was pitifully small.’ Jock Brazier (Hill 1941-45)

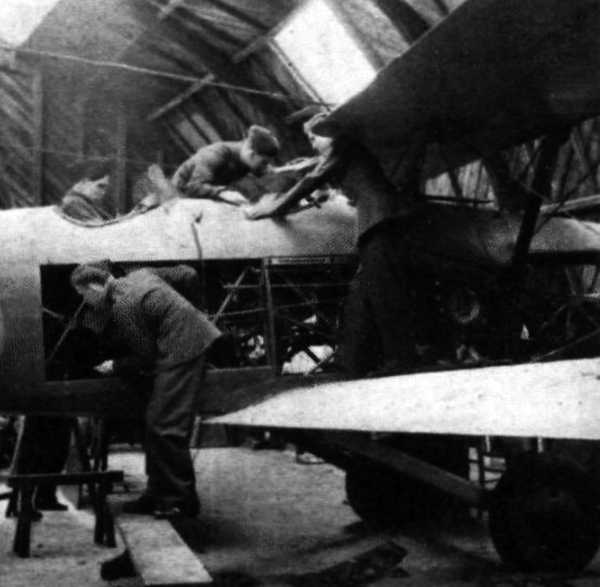

An alternative to landwork at College was aircraft repair, in a workshop near to the swimming pool:

‘I tried it for a short time but the work I was given was to sandpaper paint off some bits of metal, which bored me stiff and I returned to work on the land which I enjoyed.’ Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47)

‘…aircraft repair, which on reflection must have been a waste of time.’

John Hornibrook (Murray 1942-46)

After the War

Even when the War was over, landwork remained a part of the Wellington experience for many years, although memories differed on how frequent or obligatory it was.

John Flinn (Combermere 1944-49) wrote that ‘landwork was compulsory all my time there,’ and Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52) that ‘we had compulsory kitchen garden work, one half day every two weeks.’ However, their near-contemporaries had different recollections. John Ormrod (Stanley 1946-50) stated ‘there was very little compulsory land work, the numbers were very small,’ and Sam Osmond (Hill 1946-51) that ‘land work was only compulsory for boys who did not want to join the CCF exercises every Wednesday afternoon.’

This discrepancy of accounts was very common, and may perhaps reflect the different approaches to landwork taken by the individual Houses and Dormitories. An anonymous Wellingtonian in the Hardinge remembered having to do six landwork shifts per term, ‘but if a Prefect reported me slacking, I was given an extra shift as punishment.’ The Hopetoun prefects were perhaps more insistent than others: an anonymous Hopetoun student in the early 1950s mentioned ‘landwork required for five afternoons each term,’ and Roger Pinhey (Hopetoun 1952-57), ‘compulsory land work one afternoon a week.’

Meanwhile in the Benson, Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54) thought that ‘landwork was compulsory, and in the Benson was limited to the House’s own garden,’ but shortly afterwards, Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56) and John Thorneycroft (Benson 1953-58) recalled it as an optional alternative to CCF or games. Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948-1950) and John Green (Talbot 1954-58) concurred, the latter noting that:

‘one could not join the CCF until one had been at College for a year, so one was thrown to the (few) mercies of Mr Legg, with landwork in the kitchen gardens.’

Compulsory or not, almost all our respondents had taken part in landwork at some time during their school careers.

The main tasks mentioned were digging and weeding vegetable beds, and harvesting crops such as potatoes and carrots. One chore in particular was mentioned several times:

‘We were tasked with doing “double trenching,” which I have not met anywhere else since. This meant digging a trench one spade deep and putting the soil on one side, then lowering the trench by an additional spade, putting the soil on the other side. You then filled the trench with the first soil, planting seeds, and then covered it with the second. Tedious!’ David Trafford-Roberts (Anglesey 1943-45)

‘I learned to “double-dig,” which has been quite useful in later life!’

Hugh Trevor (Hopetoun 1943-48)

Mr Legg

For most of this period, landwork was directed and supervised by Mr H G Legg.

Appointed as Head Gardener in 1940, from 1944 he was put in charge of the College farm as well. He was described by an anonymous OW as ‘a very large gentleman who would ride round on a little grey Ferguson tractor,’ and by Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55) as:

‘a Berkshire farmer who stomped around in gumboots and had little time for lazy teenagers!’

He certainly had little tolerance for those whom he felt were not making the required effort:

‘Unfortunately, though probably not without good reason, Mr Legg took an acute dislike to me and my best friend, and would shout abuse at us every time he passed. His salvos of “You two SLACKERS –pick up them ‘taters faster, FASTER…” haunt me to this day.’ Anonymous

‘Mr Legg thoroughly hated us boys. Of course we would indulge in potato fights, hurling large King Edwards across lines in an attempt to hit one another’s heads. Legg would get hopping mad if he caught us misbehaving like this.’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

However, another anonymous OW reflected that:

‘I now realise that we learnt a good deal under the watchful eye of the farmer in his big wellies.’

Mr Legg became ill in 1955 and died in January 1956. A new Head Gardener was appointed, and science teacher George Aglen for a while took charge of organising landwork.

A pleasure or a chore?

The majority of our respondents did not express much enthusiasm about landwork. At best they regarded it as, in the words of Charles Wade (Lynedoch 1947-50), ‘not too arduous, but not very interesting.’

Many were more forthright in their opinions:

‘I vividly remember my disgust during one afternoon’s landwork at the smell and feel of clearing out a mound of slimy rotten potatoes that we were ordered to dispose of.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘There are memories of dreary afternoons “tatty-howking” on long rows…’

Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘My prep school had well organised and enjoyable work for boys, but College landwork was sullen, tedious and becoming more trouble for the gardeners than we were worth. I remember hand-weeding a field of carrots.’ Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53)

‘Landwork every two weeks was a most unpopular “change” – a run was over so much more quickly, giving more spare time.’ William Field (Lynedoch 1952-56)

‘Landwork was boring and much disliked by everyone.’ Tim Travers (Hopetoun 1952-56)

‘I remember being forced to do landwork which, as far as I remember, was mainly weeding with a hoe. I don’t remember anything enjoyable about it, it felt more like a punishment.’ Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953-57)

‘…spud-bashing on the College farm… cold and miserable wet days gathering potatoes (or stones), with frozen hands and feet and bleeding fingers.’

Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

Although only one was moved to action:

‘Although I had no reason to object to it, I tried to bring the issue before the Antislavery Society, which however failed to respond to my libertarian appeal.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

However, a few were more positive about the experience.

Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51) recognised that ‘One good aspect of land work was the ability of boys who disliked sport to choose it, rather than having to partake in, for them, dreaded sports.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48) was one of these:

‘I enjoyed this work, particularly as it released me from playing some game. It was hard work, but gave one the feeling of actually achieving something worthwhile.’

Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951-55) wrote of a pleasurable experience harvesting new potatoes:

‘I remember that they were beautifully clean and unblemished, probably because the local soil was sandy and free-draining; anyway, I enjoyed it!’

Others appreciated other aspects of this task:

‘…potato harvesting time, when the participants came away with pockets bulging with the raw material for making chips on brew rings.’

William Field (Lynedoch 1952-56)

‘Ambarrow farm was one of our Wednesday happy places. Picking potatoes behind the harvester was an occupation that stimulated much creativity. What CAN you do with a muddy spud? This venture would conclude with the mashed potato, created from spent and trampled missiles, being fed to the farm pigs. I think the pigs quite enjoyed Wednesdays!’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

While Michael Campbell (Hill 1954-59) simply wrote: ‘Working in the vegetable garden I always enjoyed – restful.’

A lasting influence?

John Green (Talbot 1954-58) considered that landwork ‘was not much fun and has put me off gardening for life.’ However, others found the opposite to be true:

‘Growing fruit and vegetables was always great fun, and inspired me to attempt to grow my own food whenever possible throughout my life.’

Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘I am still a keen (though fairly incompetent) gardener now!’ Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951-55)

‘l learnt to deep-dig: excellent later in life for my veg patches!’ Roger Pinhey (Hopetoun 1952-57)

‘I must have absorbed a bit about growing vegetables, because I have done so for the last 65 years.’ John Flinn (Combermere 1944-49)

Later in the 1950s

Towards the end of the period, landwork became less essential to the College’s functioning. It continued, but on a smaller scale.

The 1957 College Year Book noted: ‘We have found that a small shift of about six boys, under a skilled gardener, produces far more per boy than the vast herds of 50 or more, which were difficult to manage.’

Perhaps for this reason, although Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60) remembered that ‘There was compulsory land work. This made for a mid-week break in sport. I think it was quite fun,’ Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953-58)’s recollection was that land work ‘was an alternative to joining the Corps. I was never involved,’ and Michael Crumplin (Orange 1956-60) did not remember any land work or rationing. Landwork continued to be reported in the Year Book until 1965, but the link to the Second World War was by then much more tenuous. As Stuart Dowding (Talbot 1957-61) put it:

‘We had to dig in the potato field, but I don’t think the War had anything to do with it. We were cheap labour.’