Popular Culture

School life does not exist in a vacuum. Wellington may have had an insulating effect on its students during the 1940s and 1950s, but they were still aware of trends in wider society, particularly music and fashions aimed at the newly-emerging concept of the ‘teenager.’ Here we look at how these trends made their mark at College.

How much influence?

Most of our respondents felt that popular culture had little or limited influence on their lives at Wellington during the 1940s and 1950s. One of the oldest, Peter Firth (Hardinge 1941-46) simply commented that ‘It had not been invented yet.’

Many of those who came later agreed:

‘I can’t remember anything about the rock’n’roll generation or the music that it generated.’ Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53)

‘The outside world and its influences hardly impinged.’

Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52)

‘In spite of the era being the beginning of teenage culture, it had little impact in the first half of the ‘50s when I was at College.’

Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53) gave some thought to why this was:

‘An impoverished and somewhat drab British scene was still contending with post-war recovery. Our inclination, supported by a certain consciousness of class, was to respect and uphold the inherited traditions of the school, such as ‘ticking’ with the forefinger when passing a begowned usher, and long-established jargon such as ‘jallies’ for College servants and ‘squealers’ for junior boys – customs which would be swept away in the free-thinking era that was to follow a decade later.’

Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58), at Wellington a few years later, experienced the same class consciousness:

‘Elvis had certainly arrived, but I think in our tweed-jacketed, cavalry twill-trousered way, most of us thought he was rather common.’

This led many respondents to characterise themselves as, in a word of the day, ‘square’:

‘We were too early for the revolution and I remained rather solemnly square for many years.’Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53)

‘I am afraid I was very much a square! I liked only classical music.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

Several others also expressed a preference for classical music, or for light opera such as Gilbert and Sullivan, throughout their time at Wellington and beyond. Indeed, the experience of many might be summed up by John Clarke (Benson 1949-54):

‘I experienced no popular culture at Wellington.’

Fashion

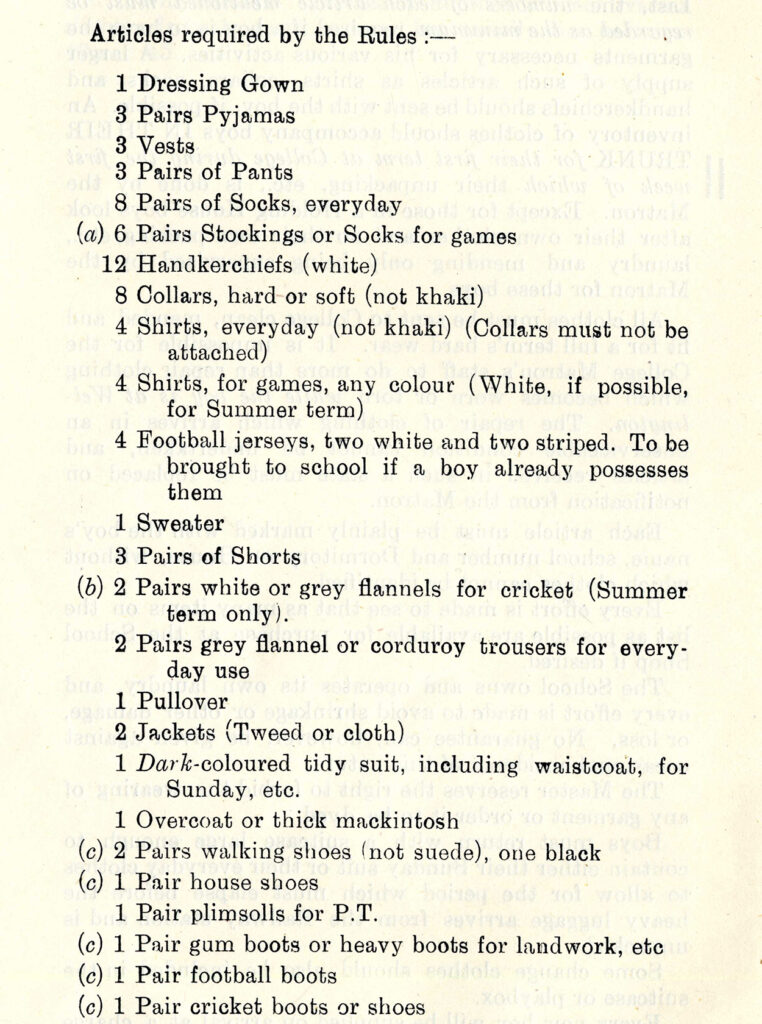

Tradition and conservatism were most fully seen in the way Wellington students of the time dressed. Of course, this was partly due to the Second World War and its aftermath. Clothes rationing was in place in the UK until 1949.

Respondents of the 1940s recalled the effects of this:

‘Fashion trends: none. Clothing was rationed, although, coming from Ireland, I was reasonably well-clad.’ John Flinn (Combermere 1944-49)

‘The uniform was not compulsory at that time due to clothes rationing; we wore flannels and sports jackets, and some form of suit on Sundays.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘Food, clothing and petrol were still in short supply… School wear had to be practical and hard wearing. Usually this was a jacket and corduroy trousers for daily wear, and a dark blue suit with dormitory tie for more formal occasions.’ Peter Ricards (Murray 1947-52)

‘There was no school uniform, but tweed jackets and blue ties were obligatory during the week and a dark suit on Sundays, affording little scope for fashion experiment.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘Dress was not a major factor in our lives. School wear was warm, practical and conventional: sober tweed coats (perhaps with the dashing addition of two side slits at the back), grey flannel trousers, and grey flannel suits for Sundays. The only distinction was in the tie, a discreet lion rampant for a College Prefect and assorted stripes for College Sports colours. Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘Our dress was about as “square” as it could possibly be. Jacket and tie, grey flannel trousers. We wore sensible leather shoes with laces. The nearest things to trainers were our gymshoes.’

Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948-1950)

A couple or respondents recorded how unfamiliar they were with more modern fashions:

‘I don’t think any of us owned a pair of jeans. When I took my sister to see West Side Story in 1958 she saw the credit for Levis in the programme and asked what they were; I said I thought they were probably the shoes!’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

‘The only time I saw Teddy Boys was quite memorable to me, when I went on a visit to the Walworth Club. They were very evident in the streets.’ Nick Harding (Combermere) 1951-1955

Looking back, John Watson (Benson 1946-51) considered it ‘strange to think that in our teens we liked to dress just as our fathers did.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56) commented that this formal wear was simply the norm for the times:

‘At my home the men were expected to put on a suit for dinner.’

By the 1950s, College dress rules had become somewhat stricter. One anonymous OW recalled ‘we had little choice concerning what to wear,’ another that ‘we did not vary our dress; the uniform sports jackets and grey flannels remained fairly firm.’

‘Dress code was generally pretty strict. Grey flannels and a shirt with a proper collar and standard blue tie, together with polished black shoes. When awarded, other ties, such as College sports colours, House colours, College Prefects, CSM etc. could also be worn. Boys’ dress was checked by the Upper Ten as they came out of the chapel each morning and anyone deemed improperly dressed was sent back to their house to correct the failing!’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

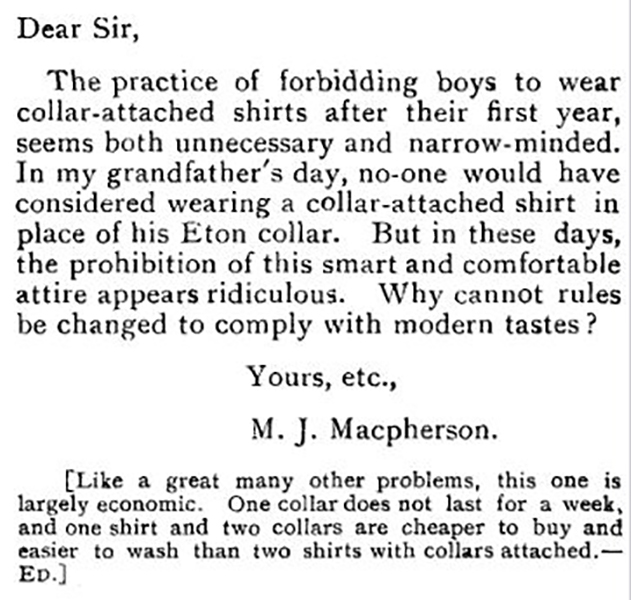

The ‘proper collar’ mentioned by Anthony Bruce was a source of pain for Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58):

‘After one’s first year, one was expected to wear white collar-detached shirts. This was alright if one could (a) afford to keep buying bigger collars as one’s neck size increased and (b) could afford to send the collars to the specialist laundry Collars of Wembley, who collected them in a special cardboard box and returned them clean later. If, like me, you had to use the rather basic College Laundry, the collars came back with a razor-sharp edge of upright fibres that cut straight into one’s neck. I remember going home after one term, my mother being appalled by the dirty and scarred “parrot’s ring” round my neck; she bent me over the sink and scrubbed it away with a cut lemon. The cure was almost as painful as the cause!’

Other seemingly small rules were also strictly enforced:

‘A tweed jacket, the number of buttons of which that had to be fastened, however, being rigidly laid down by convention.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘I never questioned the absurdity of being obliged to keep the middle button of my jacket done up until I’d been there three years.’

Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54)

‘New boys were required to have the middle button of the jacket done up for a number of terms. Also, only after a certain period of residence was one allowed to walk around with hands in trouser pockets. This, naturally, became a status symbol.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

In this atmosphere of conformity, in which the school clothing list demanded that socks ‘must be of sober hue only,’ even small variations were a means of self-expression:

‘The only latitude that I recall was in coloured jerseys which one could wear in the evening. I had a red polo-necked one.’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘As I had become infatuated with Jacobitism and the Highlands of Scotland, I once ordered myself a Highland bonnet from a firm in Edinburgh. Disappointingly, it was snatched from my head by an irate Titch Wright (our Tutor), and never seen again.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

‘Some took to wearing the most outrageously wide and colourful neckties on the last day of term.’

Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘On the last day of term one was allowed to wear any tie, so most of us tried to get something as gaudy or outlandish as possible.’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

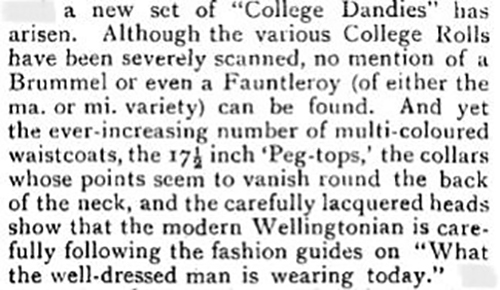

As the decade wore on, a little more latitude was permitted:

‘A few dandies wore colourful waistcoats, but not many.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55)

‘The freedom of dress allowed a great flowering of waistcoats and pullovers, together with other differentiating items from shoes to silk handkerchiefs.’

William King (Beresford 1956-61)

One attempt to make the uniform more fashionable was recalled by a couple of writers:

‘The main concession to fashion one could make was narrow (as near drainpipe as one could get away with!) trousers.’

Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

‘Very trendy at that time, rather surprisingly, was to have your trousers “drainpiped” by the Mas [Matrons]. We were surprised that the Master would allow it, and the Mas did it for nothing.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

But some trends were still discouraged:

‘Perhaps hair grew a bit longer, but the CCF did not allow it to grow too much.’ Anonymous

‘The only fashion trend that I can remember following was growing my hair long, which was actively discouraged; there were frequent instructions from the powers that be to “get your hair cut”.’ Adrian Stephenson (Talbot 1957-61)

However, in retrospect some considered that things could have been worse:

‘Wellington “uniform” was, I think, less prescriptive than some schools.’

Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

‘For the time, the rules were well thought out and allowed one a certain amount of individualism, particularly when compared to other schools. How lucky we were compared to the formalities of Eton and Harrow!’ William King (Beresford 1956-61)

Music

Music is often taken as the defining factor of a generation and its culture. In the 1940s and 1950s, perhaps for the first time, young people espoused popular music disliked or disapproved of by their elders.

The dormitory gramophone

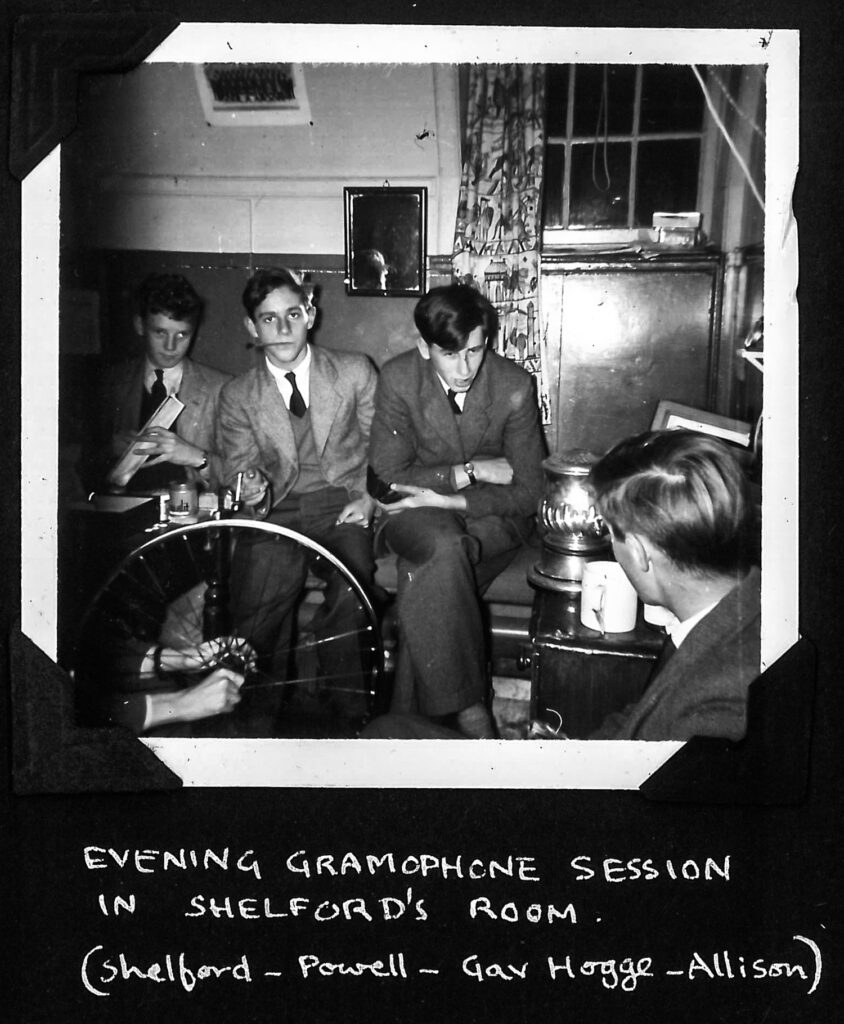

Overwhelmingly, the means by which Wellingtonians of this era experienced music was the dormitory gramophone, a fixture since before the War.

‘Music was not as universally available as now; there were no individual radios or music players. If one had records, one could play them on the dormitory radiogram when available. I think that eventually I had as many as six 76 rpm records.’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘Every dormitory had a big stand-up gramophone in the corridor which boomed out at all hours except early morning.’

Sam Osmond (Hill 1946-51)

‘We had one gramophone record in Dormitory (Bing Crosby’s “Give me land…” [Don’t Fence Me In]) which wore out from over-use.’ John Flinn (Combermere 1944-49)

‘We had a number of Irish boys in the Hill who were keen on the gramophone (“grome”) in the dormitory passage and introduced us to jazz.’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

‘In my final two years, my room was at the far end of the corridor, with the dormitory gramophone immediately outside. To this, I attribute my ability to study or read, totally oblivious to noise. A useful talent, but one that my wife has never fully appreciated.’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

The radio

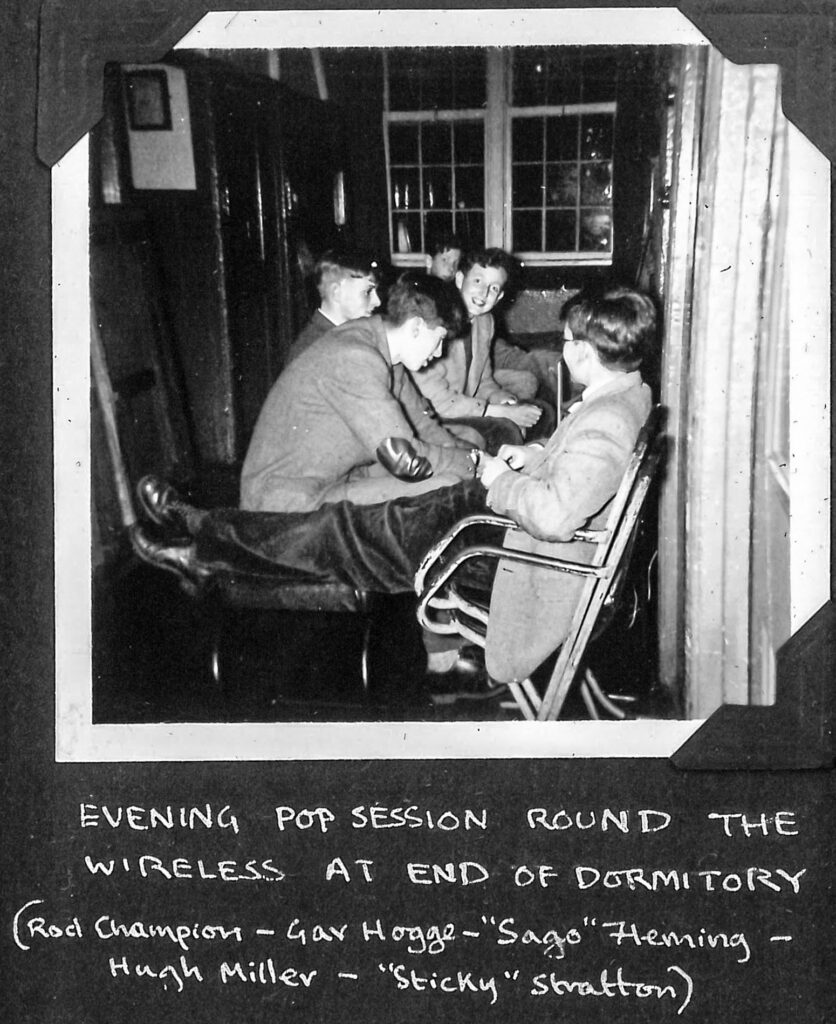

Many dormitories also had a radio or ‘wireless’, and some boys also owned or made their own.

‘I used to make one valve radios and sell them, and we use the bed springs as aerials.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘an illegal locally-made “whisker” radio and earphones, via which I liked to listen to famous jazz bands.’

Anonymous

The BBC’s Light Programme was mainstream listening, but teenagers looked elsewhere for more exciting sounds:

‘A group of us, on the cusp of adolescence, would crouch round the dormitory wireless to listen, through crackle, to Glenn Miller and the other big bands – Jack Teagarden, Cab Calloway, the Duke, the Count and other black royalty we adored, on American Forces Network.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

‘Jitterbug was brought to us by American GIs. We were still punch drunk immediately after the war.’

Richard Sarson (Hardinge 1943-48)

‘The BBC monopoly on radio broadcasting was coming to an end. The growth of commercial networks and “pirate” radio ships anchored outside the three-mile maritime limit to evade taxes and broadcasting restrictions led to a whole new paradigm of popular music. I distinctly recall being critical of the new Italian American singer who was trying to replace Bing Crosby. What was his name? Frank Sinatra!’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘There was great keenness for the Top Twenty on Radio Luxembourg – the first of the offshore stations. I judge that was at the very start of the pop culture.’ Henry Beverley (Anglesey 1949-53)

Jazz

Jazz had been popular at Wellington since before the War, and its appeal continued throughout our period. Some were great enthusiasts:

‘I discovered the extrovert freedom of Dixieland jazz thanks to my friend Robinson. I wallowed in his small collection of Louis Armstrong’s Hot 5s and Hot 7s, and Fats Waller. The latter was admired by other rebels to the extent that his photograph hung in the dormitory passage in an elegant picture frame, purporting to be our patron, Field Marshal Sir Stapleton-Cotton, 1st Viscount Combermere’. Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

‘We listened to jazz, and a favourite was Spike Jones.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘I remember listening for hours to Sonny Rollins.’

Robert Hirst (Picton 1955-59)

‘The form of music which had the most enthusiastic following in my house was jazz. The barber in Lower Crowthorne, Denis Strudwick, used to attract boys along for impromptu jam sessions.’ John Watson (Benson 1946-51)

‘One or two Londoners in the dormitory had attended jazz clubs where Humphrey Littleton had played, so we heard quite a lot of jazz, mostly blues, not modern which was frowned upon by the know-alls.’ Anonymous

‘“Dig” Scholey, later Sir David Scholey, was a great jazz trumpeter and leader of the sessions held in the music annexe, far from the dignified classical ambience of the music school. Dig introduced me to traditional jazz, which became a passion which has never left me. The Crowthorne barber, Dennis Strudwick, was a musician who played in a dance band at weekends and, for those of us into jazz, a regular haircut and chat with Dennis was de rigeur. In the school holidays we would meet up with our friends at “Mac’s”, 100 Oxford Street, where we would listen to Ken Colyer, Chris Barber, Monty Sunshine and all the other greats of the time. In the intervals, Lonnie Donegan, a banjo player, would perform his washboard “skiffle” act with which he later became famous.’ Anonymous

‘The only time I entered Chapel without religious purpose was to hear David Scholey (now Sir David) and, I think, Tim Preston rehearsing a piece of music they were to play – Scholey on trumpet and Preston on the organ. Once played through to their satisfaction, their unspoken consent turned the rehearsal into an entirely traditional jazz session which would have had Louis Armstrong’s applause and certainly delighted and rivetted my attention. David it was who introduced me to New Orleans jazz and gave me a lifetime love of it.’ John Berger (Benson 1949-52)

But of course, not everyone agreed:

I hated jazz and still do.’

Anonymous

A variety of music

Beyond jazz, Wellingtonians of the era had a varied taste in popular music.

Musicals were enthusiastically received:

‘Our pop culture was pretty tame – it ran to things like the musical Salad Days.’ Richard Godfrey-Faussett (Anglesey 1946-50)

‘A boy called Margetson in Talbot had a set of records from Bless The Bride, which was all the rage in London in 1947. We were just about to be hit by the wave of superb American musicals, Oklahoma, Annie Get Your Gun, South Pacific, etc., which were all over the West End from 1947 onwards.’ Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948-1950)

‘In summer 1951 all we College Prefects went to South Pacific, hoping in vain to see May Martin.’

‘Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

But most responses highlighted variety of artists whose voices graced the dormitory corridors:

‘There was a gramophone in the Anglesey, with a good supply of vinyl records, including Dvorak’s New World Symphony, Liszt’s Les Preludes, Phil Harris’ Woodman Spare that Tree, and the Ink Spots’ I Like Coffee, I Like Tea.’ Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947-51)

‘We were cheered along by American pop songs by the likes of Buddy Holly, Frank Sinatra, Doris Day, and shows like Oklahoma and South Pacific. Elvis Presley was still in the US Army. American jazz in all its forms was also popular, as was Jamaican calypso with Harry Belafonte.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘We listened to pop music of the day such as Put your thumbs up and say its tickety boo.’ John Stitt (Murray 1940-45)

‘Just songs, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now and Danny Kaye favourites!’ ‘Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

‘Singers liked by everyone included Doris Day and Frankie Lane.’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

‘I remember the skiffle bands – Lonnie Donegan etc – and also Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly and Frank Sinatra.’

John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58)

‘I remember Unchained Melody and Ghost Riders in the Sky, plus Alma Cogan and Doris Day.’ Anonymous

‘On the Hill radiogram I heard Oklahoma, Lonnie Donegan, The MTA Song, South Pacific, Green Door, High Society, etc.’ William Shine (Hill 1956-60)

‘My favourite popular music artists were Glenn Miller, Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley, Jim Reeves and Burl Ives.’ Robin Ballard (Orange 1955-59)

‘Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Fats Domino were big favourites.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

‘Musical taste among us young folk was decidedly eclectic compared with that of today’s youth. For a while I was entrusted with the task of buying new gramophone records for the Stanley common room collection. It ranged from superb singers, such as Caruso, Gigli, and Gobbi, through Oklahoma and South Pacific, and on (or down?) to Bing Crosby, Al Jolson, Donald Peers, Dinah Shore, et al. The latter category was markedly tuneful, if accompanied at times by somewhat banal lyrics. They certainly exerted a powerful effect on my imagination, and I can still sing some of them: e.g. Sometimes I live in the country / Sometimes I live in the town; / Last night I had a great notion / To jump into the river and drown / So Irene goodnight / Goodnight Irene. A quirky thought, I felt.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

Perhaps it was this genre which Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48) referred to when he wrote:

‘Pop music in the modern sense did not exist; instead there was a constant stream of banal, sickly sweet crooning songs, few of which have survived the test of time.’

Rock’n’roll

In the early 1950s, rock’n’roll had little influence at Wellington:

‘Rock’n’roll was just becoming established, but was somewhat frowned upon. We were given a different perspective on this by some of the young men we met at the Walworth Clubs.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘I think of rock’n’roll as being after I left – Bill Haley and his Comets hit London soon afterwards.’

Nick Harding (Combermere) 1951-1955

‘We did start to listen to some rock’n’roll music, but in the College Prefects’ study the favourite record was Eartha Kitt singing Under the Bridges of Paris. Perhaps those at College in the second half of the ’50s had a different experience?’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

Indeed they did, according to these respondents:

‘We had heard Bill Haley, but then someone’s father sent a 45 record of Elvis Presley’s Hound Dog from the USA. We were riveted and played it over and over again. Real rock’n’roll had arrived!’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

‘I remember the start of rock’n’roll very well, as I was on holiday in Berlin where my stepfather was stationed. The American community had a great cinema and my then girlfriend was a pretty blonde American so we were present at the first showing of Rock Around The Clock! She taught me to dance rock’n’roll, and I taught her Scottish dancing, fair exchange. I therefore considered myself a leading light in that skill set. And all this lost nothing in its telling at Wellington.’ William Young (Anglesey 1954-58)

‘Hugh Marston was Tutor of Hardinge for most of my time and much feared, as he was very strict and had a haughty disapproving look as he spoke to you, but actually he was very fair and gave us some latitude. He allowed me to have a gramophone in my room one term. At first I listened to popular music of the day, but as rock’n’roll took over and was quite disruptive, he simply tapped me on the shoulder at the end of term and said, “Don’t bring that back next term.” I was not sorry as I did not really enjoy rock’n’roll, but others did and kept asking me to play it.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954-57)

‘Rock’n’roll was very popular during my time at Wellington and I developed a liking – which I still have – for Elvis Presley. In the Hopetoun, Heartbreak Hotel etc. were regularly played at full volume!’

David Cooke (Hopetoun 1955-59)

‘Ww used to go for a cup of coffee at the cafe in Upper Crowthorne where a jukebox gobbled up our small change. I ran a club where six of us put a shilling into the kitty each week and we bought a new single that we all agreed on, usually picked from the charts in the New Musical Express. This meant that we usually ended up with twelve singles which we then drew lots for at the end of term, two for each of us.’ Adrian Stephenson (Talbot 1957-61)

And not forgetting the UK’s own answer to Elvis, Michael Moore (Lynedoch 1955-60) remarked that ‘Cliff Richard was it!’

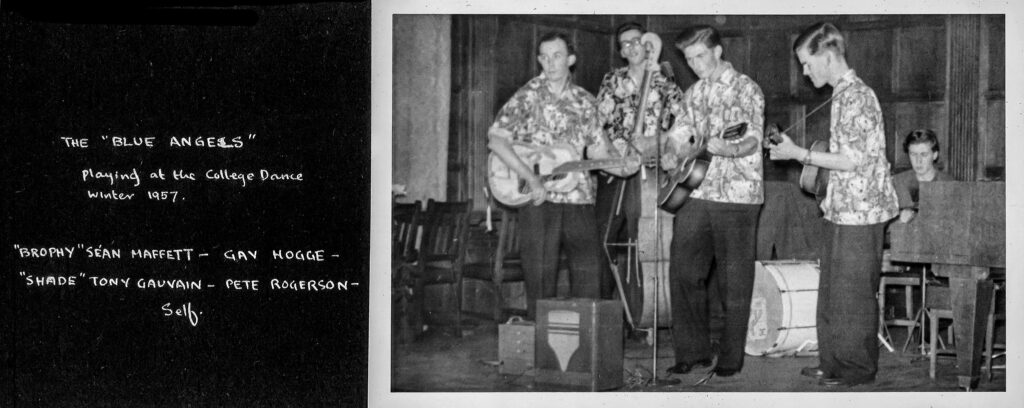

Forming bands

Inevitably, some Wellingtonians were inspired by their idols to form their own bands.

‘I joined a skiffle band called “The Blue Angels” made up of boys from the Blucher and Anglesey (I was the drummer). We were sadly equipped; Gavin Hogge the bass player had to make his own bass: initially a wooden box with a string attached to a broom handle. In time he made a full-sized, multi-stringed instrument by himself. Very amateur but a great effort. My mother scraped up enough to buy me a very second-hand snare drum and my summer fruit-picking got me a high hat.

Hugh Marston [Hardinge Tutor] called me in angrily to ask why was this band necessary. When I asked permission for us to attend the College Dance, he barked, “Certainly not! Body clutching! Upright fornication!” He relented of course. We were extremely amateur and self-taught but had a great time playing at the Dance in our Hawaiian shirts, and even at the Wellington Clubs Ball in London. We also cut a 78 rpm record at a small studio in Bagshot. A funny offshoot of this was that I was asked to drum for the Ballroom Dance Club since they couldn’t afford a record player.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

Tom’s band was remembered by William King (Beresford 1956-61), who commented,

‘High points included listening to The Blue Angels jazz band!’

Jerry Yeoman and friends also formed a band:

‘Perhaps the most notable activity of my spare time was playing in a Jazz Band. Maurice (Morry) Allen (Director of Music) had no time for jazz or any other form of popular music, and we had to take ourselves off to the old metal workshop where there was a piano that had seen many better days. We also took advantage of playing standard waltzes, foxtrots etc. for the Dancing Club (run by Mrs Meikle), and when the session was over, we’d have a short spell in the old concert hall of the music school.

Initially we had the support (and participation of) Mr Wynne Wilson from the Common Room who was a dab hand on the piano. David James (Hg) was on Trumpet, I was on trombone (later Tony Rennick (Bd), “Fruzz” [Charles] Bovill (M) on clarinet, Pete Emuss (L) on drums (later Pete Stephens (Bl)), Hank Hancock (Bl) on guitar, Ivan Lockett (Pn) on alto sax, and Graham Reid (Bd) on bass.

An enthusiastic supporter was Jack Wort (Tutor of the Talbot), who gave us the use of the Talbot Dining Room for our first concert. It was a “sell out,” with tickets actually being exchanged for cash. We finished by playing in the open air on Rockies during the interval of the theatrical skit revue We Couldn’t Help It put on by Tom Courtney Clack (Hg). I still present my rendering of St Louis Blues on the odd occasion and when there is a piano, seemingly needing to be played.’ Jerry Yeoman (Anglesey 1955-59)

Some bands espoused a more traditional form of music:

‘Five of us Pictonians set up a Scottish Country Dance group called the “MUCKLE EARNS” – translated as the “Great Eagles” – in which I chose to play the percussion. This was great fun and we put on a few concerts both inside and outside College in 1958-59. For our final concert before we all went to our new lives, we performed in front of a large audience in College. At the final bow, we were expected to stand up, dressed in our Scottish outfits. Being Welsh, I could not find a kilt, so I had to borrow one from Alpin Macgregor, our leading accordionist. Alpin was a tall Scot measuring 6 ft 8.5 ins, whilst I was a foot shorter. Fortunately, I could hide the lower part of the kilt I was wearing by standing behind the drums, which saved me some embarrassment!’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954-59)

Other entertainment

Some of our respondents recalled other forms of entertainment, beyond music.

Some radio shows were very popular:

‘There was a radio and record player at the end of the dormitory, and we all listened to Dick Barton at 5.45 before being confined to our rooms to do prep.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘We were ardent fans of Dick Barton, listened to each evening on the dormitory wireless.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘Comedy shows on the radio such as Tommy Handley’s ITMA, were regular favourites.’

Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘There was much excitement when the BBC announced the broadcast of the very first stereo sounds. We managed to scare up a second radio and set them up side by side, a big crowd gathered round to hear. It was truly thrilling, especially the ping pong game!’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

Lastly, television was just beginning to make its mark:

‘BBC Television in black and white was available in very few homes and venues, and broadcasting was limited to a few hours per day, mostly news. At home we had the normal twelve-inch black-and-white TV, fitted with a removable “Fresnel Lens” to enlarge the picture for family viewing. Most of the time the only picture available was the tuning and picture adjustment symbol. Of course, there were no TVs at College yet. Cinema films and newsreels were all black and white. We saw our first technicolour film, I think it was Sir Laurence Olivier as Henry V, on a special school visit to Camberley cinema.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘In 1951 our Tutor in the Picton, Rupert Horsley, had one of the earliest television sets. It was a large mahogany box with a tiny screen, which had a large magnifier mounted over the front of it. The black-and-white picture was really only visible if you were seated directly in front of it. Every time a car or motorcycle passed by outside, the picture deteriorated into a blizzard of interference.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

‘It was also a time when cartoon characters were extremely popular and as we had a friend whose family lived in the village, we would sneak round and watch children’s television – Yogi Bear and Huckleberry Hound were particular favourites.’ Adrian Stephenson (Talbot 1957-61)