Living Conditions

No one could ever claim that living conditions at Wellington during the 1940s and 1950s were luxurious. They had never set out to be, even before wartime privations and shortages took their toll.

Many of our respondents used words such as ‘basic’, ‘austere’, or ‘spartan’ to describe life in their Houses and dormitories. One or two went further, describing conditions as ‘verging on squalor’ or claiming to have been ‘appalled’ when they first saw where they were to live. However, such views were in a minority. Most OWs described their accommodation as ‘adequate’ or even ‘comfortable’; at the time they expected nothing more.

Hot or cold?

Being warm enough is fundamental to human comfort. One of our earlier respondents, Robert Waight (Orange 1942–46), recalled that ‘Surprisingly, despite wartime fuel restrictions, our “tishes” and all but a few classrooms were tolerably warm.’

John Berger (Benson 1949–52) commented that ‘the heating worked in winter’, while Roger Ryall (Picton 1951–56) wrote that ‘there was always plenty of hot water and hot baths were always available, plus the buildings were always warm.’

However, more OWs recalled being cold, especially in winter:

‘The heating pipes had silted up many years before and it was cold, we used to pull our clothes into our beds to warm them before getting up to dress.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945–50)

‘The winter of 1947, when the ink froze in the inkpots, was a testing time for even the most hardy. The Victorian system of cast iron pipes can never have produced much warmth, but with the coke shortage of the war years it was often difficult to tell whether the heating was on or off. Those with money purchased ex-US Air Force kapok-lined flying suits which they wore day and night – alas, I was never sufficiently affluent.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944–48)

‘In winter it was very cold. I put my feet through the arms of my overcoat in order to stay warm.’

Tim Travers (Hopetoun 1952–56)

‘My chief memory of Wellington is of being cold. I had only been in England for two years after growing up in Central Africa and was not used to the cold … I would wear three sweaters under my tweed jacket and still freeze in class. This affected my studies as my grades followed the thermometer. After winning a prize one Summer Term for being top of the class, I received a beating the following winter for dropping to the bottom and “not trying”. When the same thing happened the next year, I was sent to counselling to find out why my grades fluctuated so wildly. My explanation that I was too cold and could not learn while shivering and sitting on my hands to keep warm seemed to be dismissed as nonsense. However, I was not beaten again.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954–57)

Several also mentioned that whatever the weather, windows would be left open:

‘My Tutor Hugh Marston made it a rule that all Hardinge boys had to keep their “tish” window open at least six inches at all times. There were nights when I slept wearing a sweater, covered with all my blankets, my dressing gown and my carpet. A couple of times I awoke in the morning to find my bed covered with snow.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954–59)

Room, cubicle or ‘tish’?

‘Probably the greatest single factor affecting our lives at Wellington was the “tish” system. As far as I know, no other public school gave its boys a room of their own almost from ‘day one.’ Living, as one did, in a raucous herd, the facility to shut oneself up in the privacy of one’s own space was of enormous importance.’

Hugo White (Hardinge 1944–48)

The vast majority of respondents echoed Hugo’s views, expressing much appreciation for the Wellington system of accommodation. For most, this meant a smallish cubicle, separated from its neighbours by a wooden partition. ‘Partition’ became colloquially shortened to ‘tish’, a term sometimes applied to the cubicles themselves as well as the dividers between them. Many commented on how pleased they were with this, after having been accustomed to communal prep school dormitories:

‘We appreciated having our own private space and each made it as comfortable as was his ability to do so.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946–51)

‘To have one’s own room was a delight.’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947–52)

‘This really gave me a feeling of freedom and responsibility.’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954–59)

‘Wellington was well ahead of other schools then in providing this degree of privacy, while most other schools still used the open dormitory system.’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951–56)

The wooden partitions dividing the rooms were six or eight feet high but did not reach to the ceiling of the dormitories. Because of this, they provided, in Thomas Collett-White’s (Picton 1950–55) words, “Visible privacy, yes; audio, no.’ William Young (Anglesey 1954–58) found that ‘The dormitory was surprisingly quiet at night, no sounds of snoring’, but missiles could be exchanged between the cubicles. Robin Lake (Benson 1952–57) recalled that ‘We got very good at judging “three rooms away” or “across the corridor” with ping pong balls or old gym shoes!’

Climbing over the partitions, or ‘tish-popping’ as it was known, was strictly forbidden and punishable by beating. Nevertheless, Robert Waight (Orange 1942–46) recalled that ‘this line of approach was taken by marauding boys interested in attacking their friends using a variety of missiles, often water-filled. Despite howls of laughter on both sides, invaders were often repulsed quite savagely by flailing fists, hockey sticks, and cricket bats!’

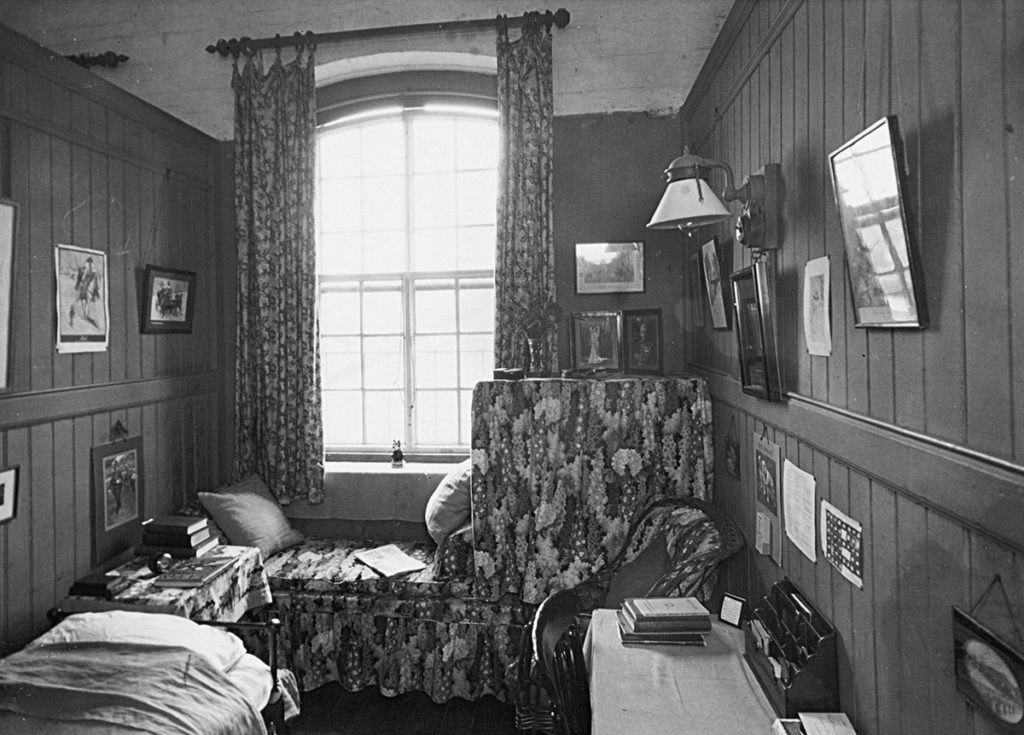

Furnishings and fittings

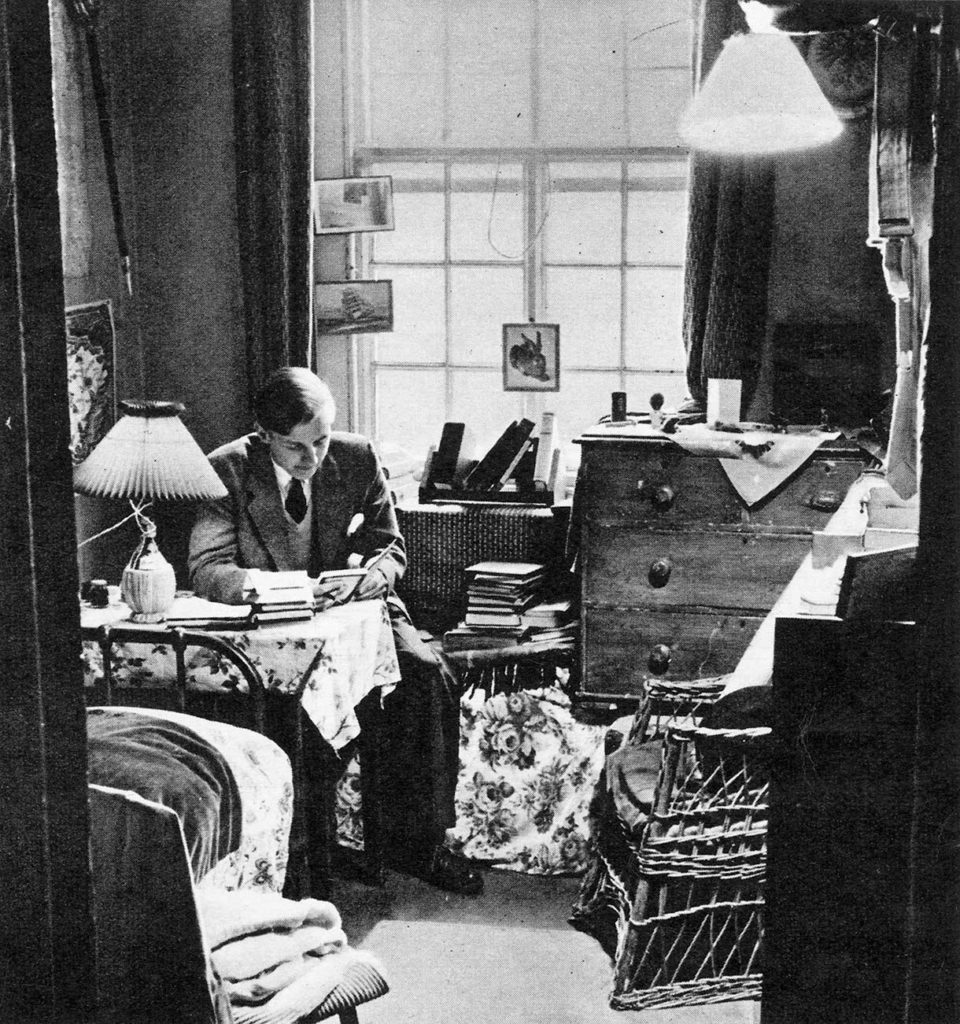

The layout and furnishings of the rooms were fairly standard, as described by Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949–54): ‘an iron bed, a desk/table with chair, a window seat with a cushion (“hardarse”) and a small chest of drawers.’

To this inventory, others added possibly ‘hooks for clothes’ and ‘a floor mat or carpet of some sort.’ Robin Ballard (Orange 1955–59) mentioned ‘a bookcase, or fitted bookshelves on the wall behind the door, with a flap-down for food’, while Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957–61) enlarged: ‘Each room had a “birdcage”, situated behind the door and over one end of the bed. This was a wooden cupboard, with three shelves and a wire mesh front, hence the name. This was useful storage for many items, particularly tins of baked beans etc.’

These furnishings were themselves pretty basic. Nigel Gripper (Hopetoun 1945–49) said his had ‘a straw mattress,’ while Martin Kinna (Murray 1953–58) wrote that ‘the old beds were awful, lumpy and made a terrible noise when one turned over.’ However, many students added more comfortable items of their own, the most popular being an easy chair of some sort:

‘I had a very comfortable padded deck chair with arms, that a sailmaker had made for my then sea-going father years before.’ John Green (Talbot 1954–58)

‘a cushion or two, a comfy rattan armchair’ David Nalder (Orange 1949–53)

‘Most of us imported table lamps, wicker chairs etc.’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951–55)

‘Namely an armchair, including cushions, and a rectangle of proper carpet, the latter to replace the insanitary hard curled coir mat … The final touches being a coloured lampshade in substitution for the chipped enamel effort provide by College and a more tasteful curtain.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957–61)

And some attempted to rearrange what furniture they had:

‘All cubicles had the same layout, with bed against a long wall and desk opposite; that is until towards the end of my time, when some bright spark experimented with turning the room round, with the bed just fitting along the outer wall next to the window shelf with the long hardarse and triangular hardarse. This worked very well, and was copied by a large number of the boys in our corridor. The new arrangement seemed to give more space, and was open-mindedly permitted by our Tutor, Mr Marston.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946–51)

‘At the start of every term I would rearrange the furniture within the very limited scope available. The head of the bed would be repositioned to the opposite end. This allowed me to have, on the provided table, my own bedside lamp, height increased by placing the obligatory copy of Shakespeare underneath. I think that that was the only use to which said mandatory volume was ever put.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957–61)

‘As well as decorating our “tishes” to our personal taste, we rebelled against the conformity they imposed by rearranging them from time to time. Given the tiny area available, this practice, while stretching our imagination and back muscles, achieved little. A “tish” remained a “tish”.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942–46)

Technical improvements

Many also demonstrated ingenious uses of technology in their rooms:

‘I ran a system of strings round the room so that I could open and close the curtains without getting out of bed.’ Vernon Phillips (Murray 1951–54)

‘There were personal attachments to the lighting systems allowing you to put them on and off when you wanted.’ Hardy Stroud (Combermere 1950–55)

‘This involved stringing up some very dicey wiring to set up lights in different locations. Nobody objected to this amateur wiring, but they should have! It was downright dangerous.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954–57)

‘For some reason when the Bishop of Portsmouth visited College, my room was chosen to give him an idea of our living quarters. I had rigged up a lighting system in the room which he wanted to try out. He was too enthusiastic in pulling the cord and the whole lot fell down on him!’ Alan Saunders (Orange 1957–60)

‘When I was 15 or 16 I was appointed Dormitory Electrician with no training or instruction. I frequently mended fuses and did well to avoid electrocution!’

Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953–58)

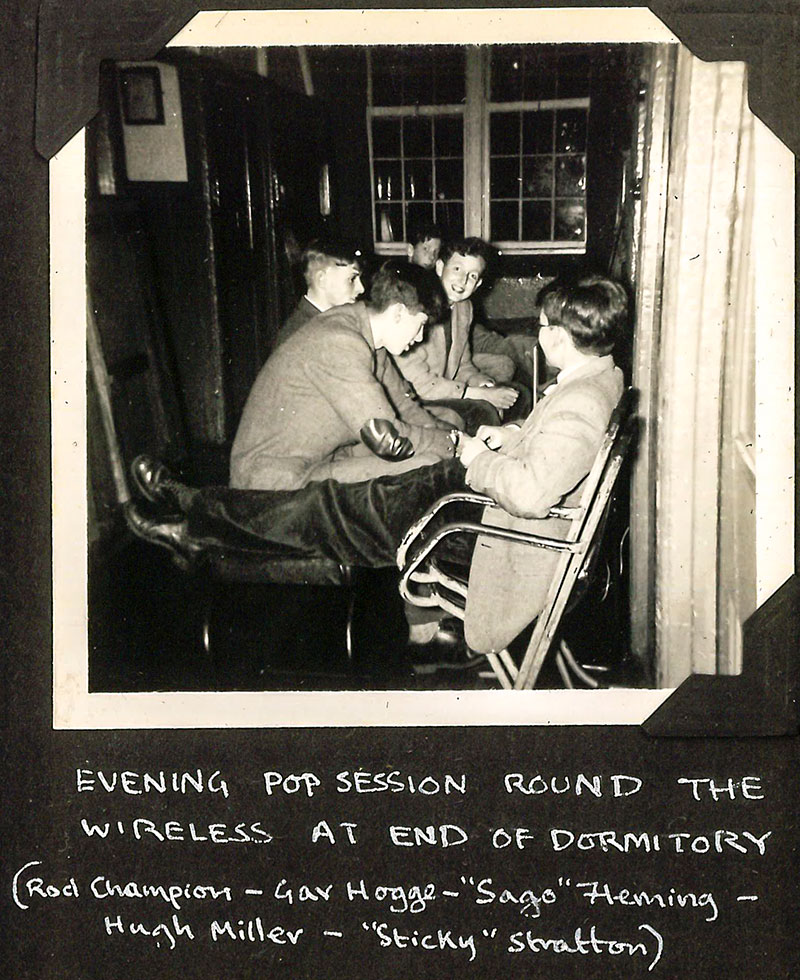

Not to mention the cat’s-whisker or crystal radio sets possessed by some, despite being forbidden:

‘I used to make one valve radios and sell them, and we used the bed springs as aerials.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945–50)

‘I tried out a crystal radio set with earphones for a while to hear the news, but there was such poor reception, I gave that up.’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954–59)

‘I had a crystal set which enabled me to tune in to some stations and listen in my room with headphones. Unfortunately one night I went to sleep with my headphones on and was found out by the Prefect doing “callover”. This resulted in me getting beaten by Head of Dorm David Mordaunt, who was subsequently a very good friend!’ Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953–57)

‘Tish rags’ and other decorations

The wooden partitions separating the cubicles were of no great beauty, being old and often in poor condition. Those in the Beresford were painted a shade described by one respondent as ‘eau de nil’ and by his contemporary, rather less attractively, as ‘puke green.’

To cheer them up, and further personalise their living space, Wellingtonians decorated them with a wide variety of colourful cloths known as ‘tish rags’, and with pictures from home, the variety of which demonstrates the range of interests at the time:

‘Nearly all of us draped our walls with swathes and swags of material, the gaudier the better. These “tish rags” probably originated in the souks, bazaars and markets of Asia and Africa, in which our parents had haggled during their service to King and Empire.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942–46)

‘Pictures were usually the centrefold of Eagle comic.’ William Shine (Hill 1956–60)

‘I used the coloured covers from The Field plus the odd picture of a film star (they usually wore more clothes in those days!). Most attempted to create a more sophisticated atmosphere using darker shades for one’s table lamp, although the effect was often more that of a courtesan’s boudoir than that of a sophisticated man-about-town!’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951–55)

‘I decorated the walls with some line and wash lithographic prints from Senefelder BV in the Netherlands, given to me my stepfather who was a craft lithographer.’ Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951–55)

‘I covered the walls with a mixture of my grandmother’s watercolours and Soviet propaganda posters obtained by my stepfather!’ William Young (Anglesey 1954–58)

‘Mainly pictures of military hardware, planes, tanks etc.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952–55)

‘My walls were covered with pictures of trains – I was developing a proper interest in railway history (more than just “trainspotting”) and transport history in general.’ Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948–1950)

‘I had a picture of a train – Stephenson’s Rocket or something similar that I brought from home – but it was just before posters became so fashionable.’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951–56)

‘I hung up a large lithograph depicting Bonnie Prince Charlie with Flora MacDonald, and other characteristic scenes of Highland scenery and history.’ Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949–53)

‘I bought a bolt of maroon fabric that served as my “tish rag” throughout the five years … I do not really remember what I had except a cinema poster or two, one I think was Carmen Jones. I was teased for having a picture of Marlon Brando in Streetcar, and I remember having a small old shell case that had been made into a little vase in which I used to stuff wild flowers and grass. These things were considered quaint or “queer”!’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953–58)

‘Decorated tea towels were popular, and I recall supplementing mine with a set of posters portraying Commonwealth parliamentary buildings and other historic sites, which I had obtained free from National Savings. Also, along what was the equivalent of the dado rail, I displayed a large number of brewery and cider company drip mats, again all freely acquired. Little did I know that in later life I would spend over 30 years working for a brewery company …’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957–61)

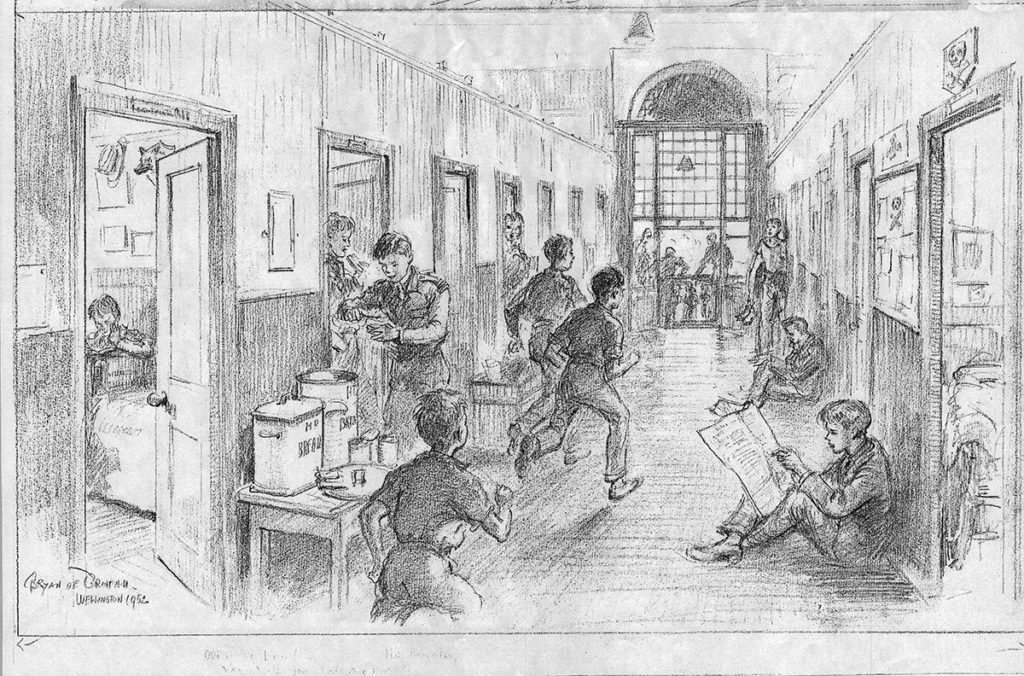

‘The drawing of the Hill by Bryan de Grineau for the Illustrated London News in 1952 gives a very good idea of the dormitory, with the “swipes” made available every afternoon, a Prefect calling his fag, and the balcony at the end looking down to the lake. The room on the left was mine; I still have the fox mask on the wall and that is presumably me reading!’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947–52)

‘I hung up a skinned jay which I had found dead on the ranges having seen it being killed by other jays in a fight.’ Anonymous

‘In the Summer Term I had a window box with geraniums!’ Christopher Miers (Beresford 1955–59)

‘Pin-ups were de rigeur. Nothing remotely pornographic, of course: the most daring were, perhaps, of Betty Grable showing off most of her million-dollar legs but otherwise modestly clothed. I contented myself with a close-up shot of demure, lovely little Dorothy Maguire who, I was convinced, would willingly have given solace to any overheated fifteen-year-old, but specifically me.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942–46)

‘My two pin-ups were Grace Kelly and Brigitte Bardot.’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953–56)

‘When I left, there were some 128 different pictures of Brigitte Bardot displayed across all the walls – and a watercolour of the Norfolk Broads.’

John Green (Talbot 1954–58)

‘The preference was for “pin ups” of female film stars – Grace Kelly, Glynis Johns, Vera Lynn. I was pleased to hang a couple of grotesque caricature sketches I had picked up in Paris during a visit to a family in Normandy to improve my French.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948–53)

‘A photo of the Yugoslav star Mylene Demongeot culled from Everyman’s Magazine.’ David Nalder (Orange 1949–53)

‘We plastered our walls with family portraits and felt at home! I had a pretty sister, and seemed to get a lot of visitors!’ David Simonds (Orange 1941–46)

Peter Davison (Beresford 1948–52) recalled another function of ‘tish rags’, beside decoration: ‘My study was the one used by Auchinleck when he was at College. On a return visit he asked for “tish cloths” to be taken down so he could find the hole he had made in the ‘tish’ to speak to his neighbour after lights out.

The rooms could hold other secrets too: ‘Certain studies had “secret” loose floorboards that provided space to mature the potato brandy being made. Occasionally there was a disaster and an usher working in the classroom below received an unexpected shower.’ Other clandestine practices included, according to Allen Molesworth (Blücher 1945–48), ‘creeping out of our windows into the gutter to smoke cigarettes; something which one had to do because it was forbidden’, and of course the time-honoured practice of carving one’s name into the brick or stonework by the window.

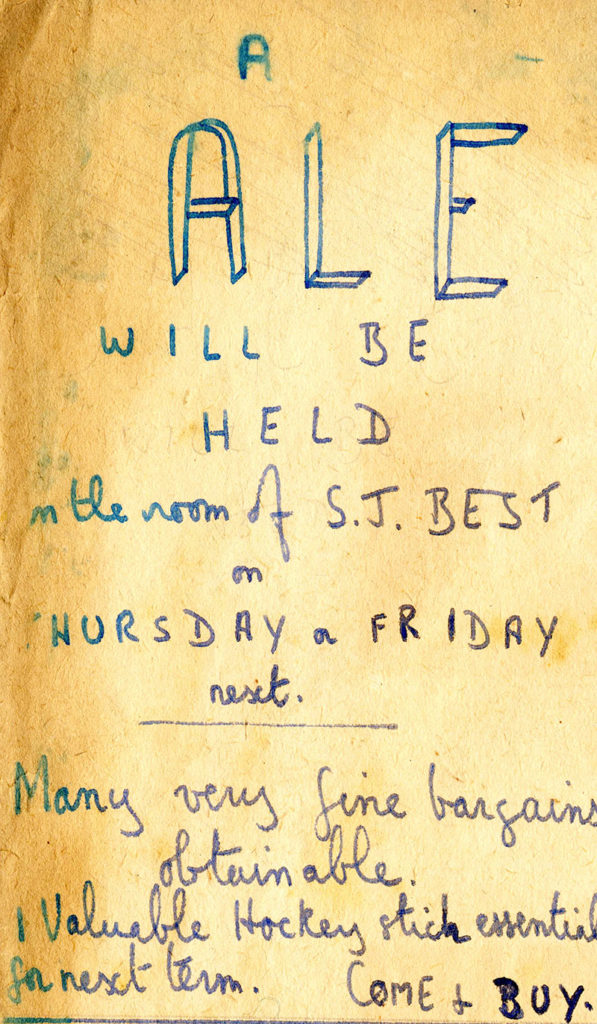

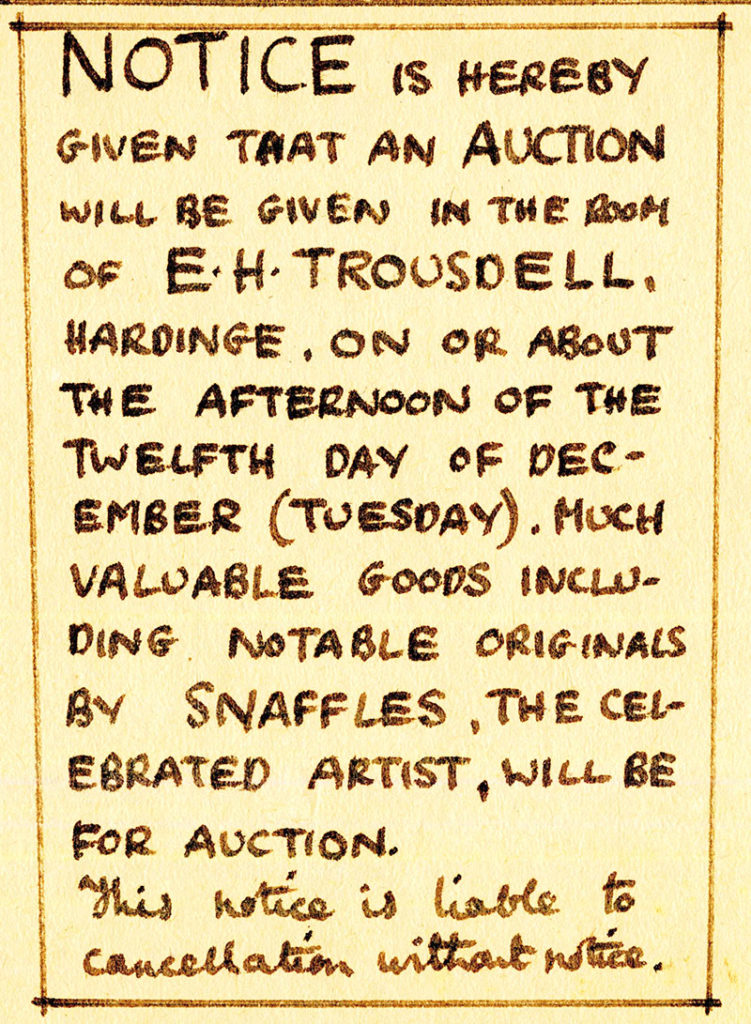

Several respondents described the way in which decorations for one’s room could be acquired:

‘At the end of each term, those about to leave College would hold an auction of the various nick-nacks they had acquired during their time. Participants would sit on the top of the “tishes” to make noisy bids for such things as pictures, cushions, or dormitory caps.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947–52)

‘At the end of each term leavers would hold auctions of anything they were not going to take back with them. Traditionally these included Corps boots, sometimes jackets they had grown out of, hockey sticks, rugger boots, pictures, small objects like trench art pieces, and sporting gear, sometimes to include the odd jockstrap. Depending on the leaver’s popularity and image, these items sometimes fetched a good price!’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953–58)

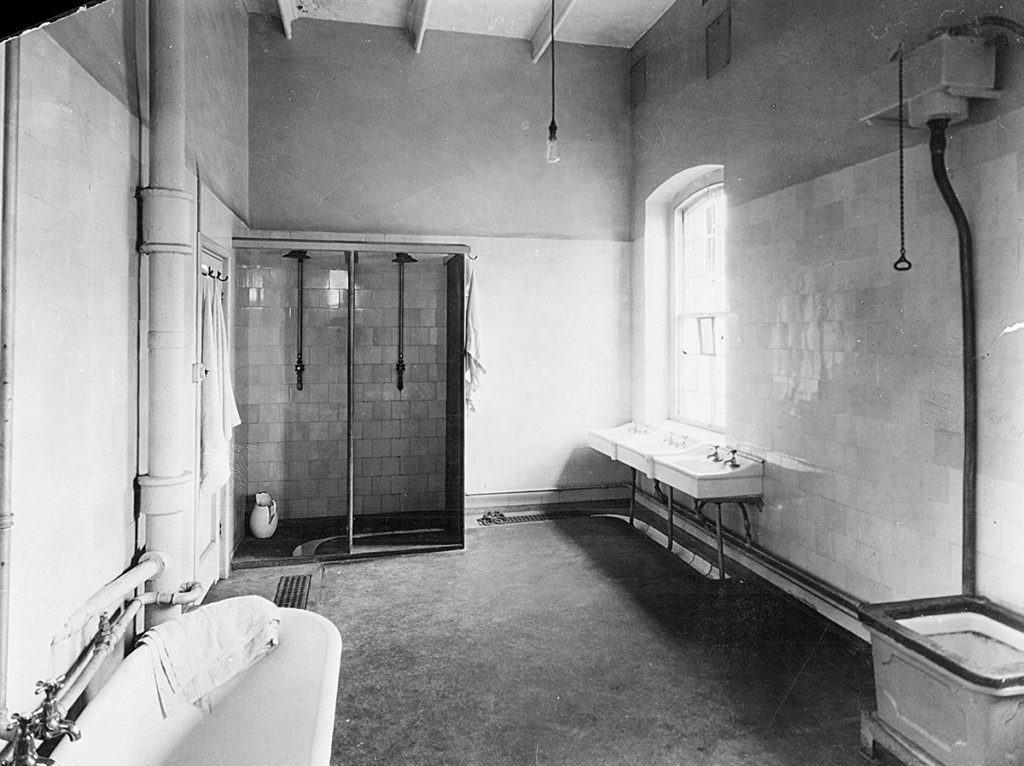

Bathrooms and toilet facilities

Expectations of what constitutes ‘normal’ with regard to bathing and cleanliness have changed considerably in the seventy years since our respondents were at Wellington. Today’s students would probably not credit their forebears’ recollections of bathing habits and the facilities provided.

‘Picton had hip baths for juniors, the two full length ones being reserved for Prefects and seniors. Heating was a luxury that felt absent from this tiled room.’ Anonymous

‘We had two baths, four basins and two non-working showers for half of the House. When I was a Prefect, there was a stokers’ strike and we had to stoke the boilers. This we did to such success that, on turning the tap on, nothing but (very hot) steam appeared!’ John Green (Talbot 1954–58)

‘We had to leave the water in the bath for the next one to get in. It was changed after three had used it. Bath days and times were designated.’

Nigel Gripper (Hopetoun 1945–49)

‘The only really warm place in dormitory was the bathroom. Fitted with two undersized baths, in which we were allowed two ten-minute slots per week, the bathroom became the forum in which we gathered nightly for general social intercourse. The baths were filled with hot water at the beginning of the evening; thereafter they were topped up from time to time, but otherwise the water was left unchanged. By the last baths of the evening, the water resembled the contents of a Singapore monsoon drain.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944–48)

‘The ration was two baths a week, some during first prep, some during second. Water depth was not allowed to exceed a black line marked on the inside of the two baths. As the baths were not plumbed in, wastewater ran into an open gulley. Rather than waiting for the water to drain out in the normal way, rapid changeover could be achieved simply by tipping the bath, with or without occupant, on its side.’ William Field (Lynedoch 1952–56)

‘The consequence [of these open drains] was that if too many of the washing facilities were unplugged at around the same time the gully tended to overflow, the result being a cascade down the main Murray/Hopetoun staircase. The floor, when walked on in wet feet would come off on the foot in a grey colouring. Hence one endeavoured to step from the bath directly onto the bench seat. This was easier from one bath; from the other one risked slipping and doing oneself a painful ‘mischief’.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957–61)

‘The bathroom was awful, though the water was always hot. My tutor refused to permit shampoo, saying that soap was good enough. I think he was to blame for my thinning hair later in life!’

William Young (Anglesey 1954–58)

‘There were two shorty baths and numerous basins per dormitory bathroom. You were scheduled one bath a week, a five-minute immersion. You were dragged out by the next boy waiting, watching the clock so he didn’t lose time. Water was only changed after every second boy, the time restarting with each new fill. But then, in the changing rooms downstairs you could shower after games each day, so you were probably cleaner than it might otherwise appear. There, there were footbaths, about two feet square and ten inches deep. I imagine they were put there for your feet, but you could sit in them, in hot water, your bottom nicely warmed, with your feet on the floor in front; and there were hot showers as well.’ John de Grey (Blücher 1938–43)

‘For use after sports, each dormitory was allocated a section of the changing rooms. Each contained a line of about eight “bimbaths.” Each resembled a laundry trough large enough sit in. They were used daily.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947–52)

Some had even worse to endure:

‘At one time we were required to have a cold bath, once a week maybe. The bath was run and one had to immerse oneself up to the chin.’

Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947–51)

‘Presumably in order to make us tough and Spartan, all the boys in the Blücher were obliged to have a cold bath before breakfast every morning, winter and summer, and the Housemaster kept watch to ensure that the cold water went over our shoulders! Not all of the dormitories had obligatory cold baths, and those which did not were thought rather effete.’ Peter Bell (Blücher 1943–48)

And then, of course, the lavatory arrangements. Robert Waight (Orange 1942–46) recalled that in his time, boys in the Orange were still supplied with chamber pots, which were emptied daily by the ‘jally’. ‘I suppose we were provided with pisspots because the nearest lavatory was at the foot of a stone stairway three storeys below.’ By the 1950s this seems to have been discontinued, but facilities were still not ideal:

‘The lavatories (as they were called in those days) were distinctly poor with some of them being open. No doors.’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954–58)

‘Shortage of WCs made the post-breakfast period quite unpleasant as such a rush.’ John Le Mare (Stanley 1950–55)

‘We were given one Jeyes box of “loo” paper per boy per month.’ Ian Nason (Orange 1950–54)

‘Lavatory paper was a box per boy issued termly; some merriment ensued such as writing to Jeyes asking how to replace unused sheets in the folded box.’ Tim Reeder (Picton 1949–53)

‘I seem to remember that argot for a toilet stall was a “back/s”. Those belonging to the dormitory were communal and were located just outside the dormitory entrance and opposite the stairs. I doubt that the facility would ever pass any health inspection.’ Chris Heath (Beresford 1948–53)

Houses vs Dormitories

Those Wellingtonians who lived in Houses in the College grounds paid higher fees than those in the central dormitories.

This was to reflect a supposed higher degree of comfort in the Houses, which were perhaps warmer and, during the earlier part of this period, had their own in-House kitchens. Some Houses had further advantages, notably the Talbot, in which the boys’ accommodation had been completely rebuilt in the 1930s:

‘Talbot was by far the most modern House, and we benefited from that. Accommodation on two floors, good facilities, common room, dining room, changing rooms etc. The House Tutor’s house was connected, and we had a tennis court and a big gravel quad. Being so far from College was something you got used to – do not leave things behind! We appreciated this distance and in fact felt slightly superior. Added pluses were our closeness to the theatre, the swimming pool, the woods (great for smoking) and the proximity to the real world of the main road to Crowthorne and the houses beside us.’ Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953–56)

‘We were comfortably accommodated in the 1930s-built Talbot. Conditions in the dormitories within the handsome but austere main College building were more primitive. One disadvantage of being in a distant House was a disconnection outside of classes and sports from the more corporate society of boys in the dormitories within College.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948–53)

‘The floors were polished oak, with substantial furniture and leather sofas. It had a most attractive “private side” for the House Tutor, with a rambling garden into which we were allowed to disappear. We felt very much on our own with House customs, such as an annual “squealers day” in which the squealers or juniors ran riot. This was an excuse for what can only be described as ball fighting, in which a general free for all transpired with one’s nether parts being attacked in an innocent but rumbustious manner.’ Colin Mattingley (Talbot 1952–56)

‘The only disadvantage of Talbot was that it was remote from the main buildings, and it seemed that we were for ever walking up to College or back, despite all weather conditions, and in those days the winters were certainly colder. We also had to take with us all the books we needed for the day’s lessons, tucked under our arm.’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954–58)

Those in other Houses, and the curiously in-between facility, the Picton, also felt at an advantage:

‘The lavatories and showers in the Picton were good by main College standards.’ Tim Reeder (Picton 1949–53)

‘The Benson was very comfortable. Four in a room in the first year, then individual “tishes.” Lovely views of the garden and woods and magnificent Wellington grounds.’ Robin Lake (Benson 1952–57)

Inhabitants of the Dormitories consoled themselves in their own way:

‘The Anglesey was one of the old original Dormitories and I recall an unwritten and never formally acknowledged feeling of superiority over the “out of school” Houses.’ Jerry Yeoman (Anglesey 1955–59)

‘I was in the Hardinge, which then was set above the Combermere, aloof from the other Dormitories. This made us feel special, and I still feel that we were.’

Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946–51)

‘Houses were more expensive than Dormitories, and their inmates enjoyed a more refined lifestyle than dormitory men, who considered them upper-class twits. A few were, but even now I am startled to recall how a quite vicious class distinction could be worked up between boys of essentially the same background.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942–46)

And there were even one or two day boys, whose experiences were rather different:

‘In my first two years I was one of only two day boys. There were several disadvantages to being a day boy and I was certainly regarded as a second-class citizen by my peers in the Combermere. On one occasion someone tore up all my work books. I had to share a “tish” with another boy who, understandably, didn’t like that at all. After I became a boarder, life became easier and I started to enjoy school life and the last 2 to 3 years were very happy.’ Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953–58)

‘My father was an usher and Head of the Mathematics Department at Wellington. My elder brother was in the Hopetoun, and for a while the only day boy. He was boarding by the time I went to the Combermere as a day boy and after a few terms I too became a boarder. I do not remember any awkwardness about being a day boy.’ Richard Buckley (Combermere 1941–45)

Perhaps the importance of one’s place, be it House or Dormitory, is summed up by Richard Merritt (Picton 1954–59):

‘Your Dormitory was central to your life. It was where you discovered how to co-exist with other people both as individuals and as colleagues when the Dormitory had to work collectively. The principal moral I drew from my time at Wellington was the sense of belonging the dormitory system gave and the corresponding duty you owe to the Dormitory.’