Health and the ‘Sanny’

Although young people are by and large healthy, medical care has always been an important part of Wellington College’s provision for its students. In the 1940s and 1950s, mass vaccinations were just beginning, and so waves of infectious diseases swept through the College. In addition, there were the usual schoolboy injuries, but all could be assured of efficient care at the Sanatorium.

Medical facilities

Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53) described the function of the Sanatorium:

‘a combined doctor’s office, first aid station and mini-hospital. It was in a separate building, reasonably well located, being close to most dormitories as well as to the ‘war zones,’ alias the rugby grounds and hockey pitches.’

Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61) listed the facilities:

‘The College doctor, C F G Hawkins, was full-time, as were the nursing staff, consisting of the Sister in Charge, Miss Attenborough, and three qualified nurses. The doctor held a daily surgery. There was also a dentist’s surgery for the part-time visiting practitioner. There was a waiting room and a dispensary… Downstairs there was a very well-equipped day room, with a good selection of novels and more erudite editions as well as jigsaw puzzles.’

The scope and efficiency of the medical care at Wellington was praised by many. Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52) felt that ‘It was comforting to know that a fully professional medical team was always on hand.’

Injuries and illnesses

The reasons given by our respondents for visiting the Sanatorium were many and varied. Several spoke of injuries such as sprains, cuts and bruises, and in some cases broken bones. Often these injuries were the result of sport:

‘…winter rugby, which seemed to produce regular visits to the Sanatorium.’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

‘I broke my arm playing rugger on Derby Field and had to walk back to the Sanatorium, from whence I was taken to Rowley Bristow Hospital where I was operated on.’ Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953-58)

‘…pulling a muscle running against Pangbourne.’ Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

‘I was in a dark room in the Sanatorium for a week as a result of a freak accident when a squash ball hit my eyeball.’ John Ravenhill (Orange 1953-56)

‘…due to boxing: I had nearly bitten through my cheek and needed a couple of stitches (no headguards then).’

Randal Stewart (Anglesey 1953-56)

‘A broken nose from boxing (I won!), and spikes through the top of my foot during the 100 yards sprint (I lost, but the blood caused a lot of interest: “Hey Lake, did you know your shoe’s all red?”)’ Robin Lake (Benson 1952-57)

‘I spent eleven days in the Sanatorium after fracturing a patella while running the 220 yards. I passed the standard but then the pain kicked in and I was carted off to St Thomas’s in London.’ David Nalder (Orange 1949-53)

On one occasion, the sport was only indirectly to blame:

‘I had a day in the San on Sports Day, when I got food poisoning from an opened tin of pineapple given to me by my main opponent in the 440 yards race. Sad, ‘cos I expected to win!’

Vernon Phillips (Murray 1951-54)

But Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56) considered that sport improved his health:

‘I was in the Sanatorium on a number of occasions, particularly in my early years. I had suffered from asthma and was subject to bronchitis in the winter and spring, until my determined cross country running finally cured me of it!’

Many also spent time in the ‘Sanny’ due to ailments such as earache, sinusitis, tonsilitis and sore throats, or more serious illnesses such as mumps, jaundice and glandular fever. Pneumonia also affected several, some very badly. Hardy Stroud (Combermere 1950-55) wrote of ‘double pneumonia when my life was in the balance.’

A few suffered recurrent ill-health:

‘I was in the Sanatorium on occasions with stomach troubles, never understood or diagnosed until I was sixty, when it turned out I was a coeliac. I doubt if anyone had heard of such a complaint in the ‘50s.’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘I was in the San quite regularly, mainly with ear trouble, sinus problems and general malaise. During my time at College I grew from 5’6” to 6’3’’ in 3 years, and this growth rate was most debilitating and went unrecognised as a cause of my poor health. Dr Hawkins and Sister Hall and her staff did their best, but I found it difficult to cope with the rigours of the school, particularly in winter.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55)

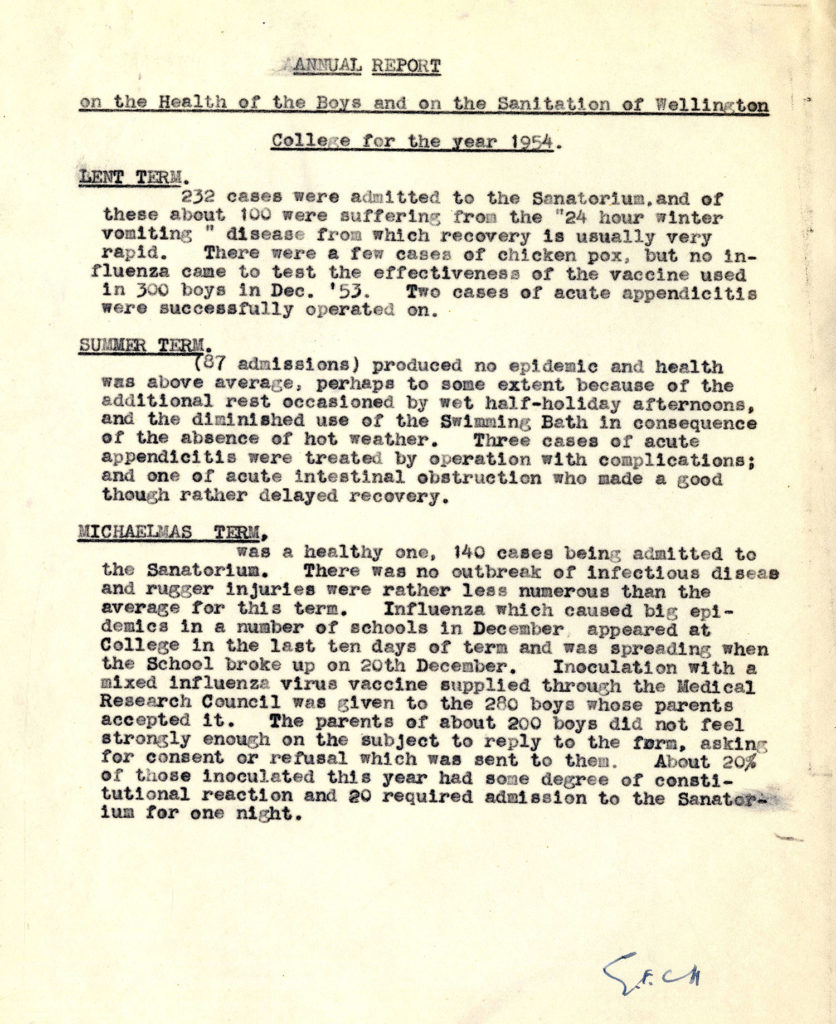

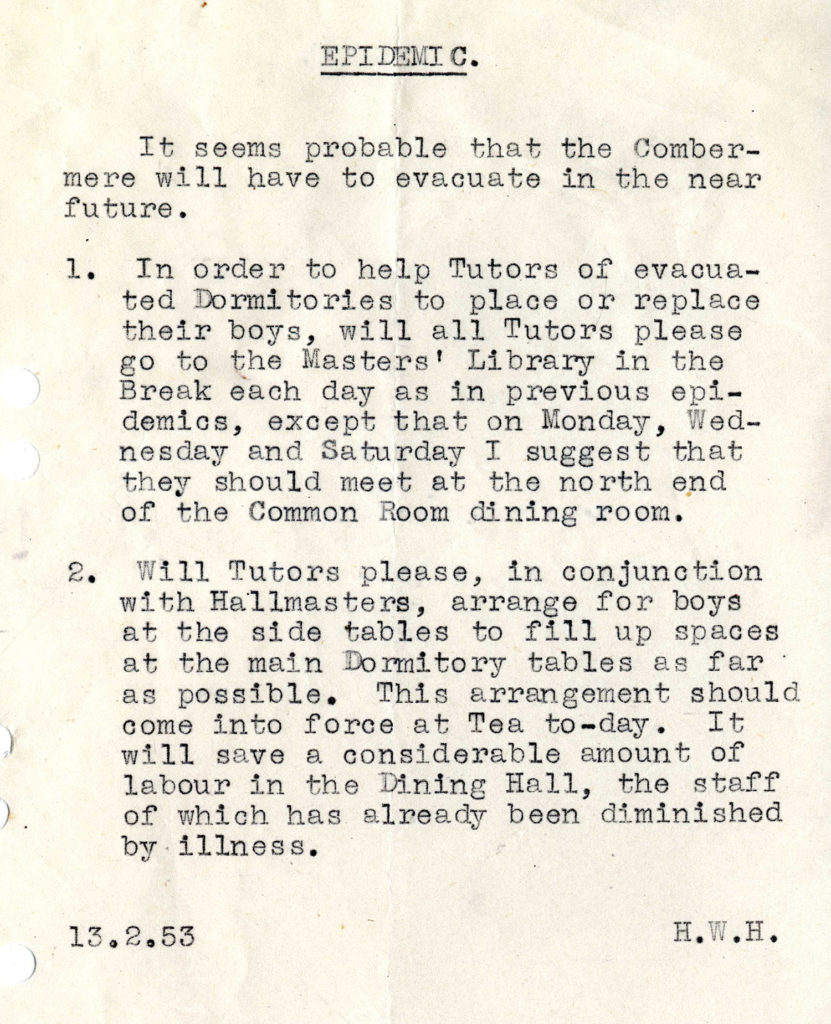

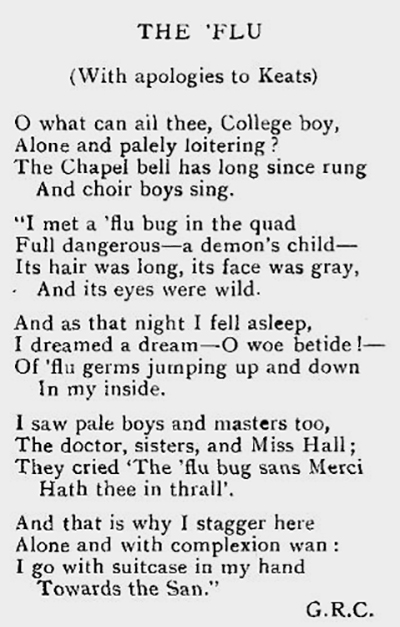

Epidemics

Waves of contagious diseases swept regularly through Wellington during the 1940s and 1950s. They were usually labelled ‘epidemics’, even if only at the school, rather than at national level.

Dick Barton (Lynedoch 1938-42) remembered one of the most serious of these, before the Second World War:

‘During the polio scare we were moved to different dormitories and at one time I was almost the only boy left in College – very empty!’

Measles was another disease which tended to affect many boys at once, and was sometimes serious:

‘I recall a serious epidemic of measles one winter, when the Talbot was turned into an isolation infirmary and its boys were scattered elsewhere; I was decanted into the Benson for a month.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘When I was sixteen or so, I succumbed to a wave of measles which affected Wellington. I think I must have been quite ill; not only could I not go home for a couple of days after the end of term, but I have a clear memory of Dr Hawkins, when doing his rounds, telling another boy to be quiet, as “there is a boy in here who is very ill indeed.” I realised he was talking about me, and quickly got better.’ Neil Munro (Talbot 1952-56)

The most common of these ‘epidemics’ was flu, which affected many boys at once, often meaning that additional buildings, usually ‘out’ Houses, were used for nursing. This phenomenon was mentioned both by the invalids, and those who were moved to accommodate them:

‘In two Lent terms we had flu epidemics. On both occasions I was a victim and as the Sani was full, it meant being accommodated. On one occasion I was put into the Stanley as it was used to temporarily house the sick.’ Charles Wade (Lynedoch 1947-50)

‘I remember spending a few nights in the Talbot, which was being used as an overflow during a flu epidemic.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘I recall being uprooted in a flu epidemic, and spending some time in a very comfortable room in the Hopetoun Annexe, the Talbot being used as an extension to the Sanatorium.’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

‘…during an epidemic when the Benson was taken over as an extra San, having to be relocated in the Beresford. Horrors!’ John Thorneycroft (Benson 1953-58)

‘In a major epidemic, I was transferred to the Combermere, where there was a kind message from the owner of the room, beginning “Dear Sanny Weed” (a term of the time). I think he had left something of interest or value for me. His name was Innes.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

Almost everyone at Wellington in 1957 remembered the ‘Asian flu,’ a true epidemic which swept the world at that time:

‘I was at Wellington during the Asian flu epidemic in 1957 and spent two weeks or so in the Sanatorium.’ David Cooke (Hopetoun 1955-59)

‘The biggest medical event in my time was the 1957 Asian flu epidemic. Several Houses were converted to overflow sick quarters. I spent a few days in the Benson, feeling fairly ill.’

Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

‘The 1957 Asian flu epidemic flattened most of the population and I spent a week in the Talbot, which had been converted into a sanatorium.’ Ross Mallock (Murray 1954-59)

‘I was in the Sanny with Asian flu, and my mother was drafted in as a nurse (she trained at Tommy’s before the War).’ Stuart Dowding (Talbot 1957-61)

Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58) was particularly badly affected:

‘I caught it very badly, and was found thrashing about in bed in my “tish” by an agency nurse. Dr Hawkins was summoned, carried me to his car, and got me to bed in the Sani. I remember waking from a deep sleep to find three nurses by my bed. I asked what time it was and they said, “You mean what day is it? You have been unconscious for over forty-eight hours, you sweated through your mattress and we had to change it!” They had quite literally helped to save my life.’

Treatment

When it came to the treatment on offer, one procedure seemed to be remembered the most:

‘Whatever the ailment, the cure always seemed to be a painful penicillin jab in the bottom. Remarkable that none of us became immune to the effects of penicillin’. Andrew Dewar-Durie (Talbot 1953-56)

‘…the discomfort of daily jabs with penicillin (still a new-fangled medication) into one’s posterior.’

Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

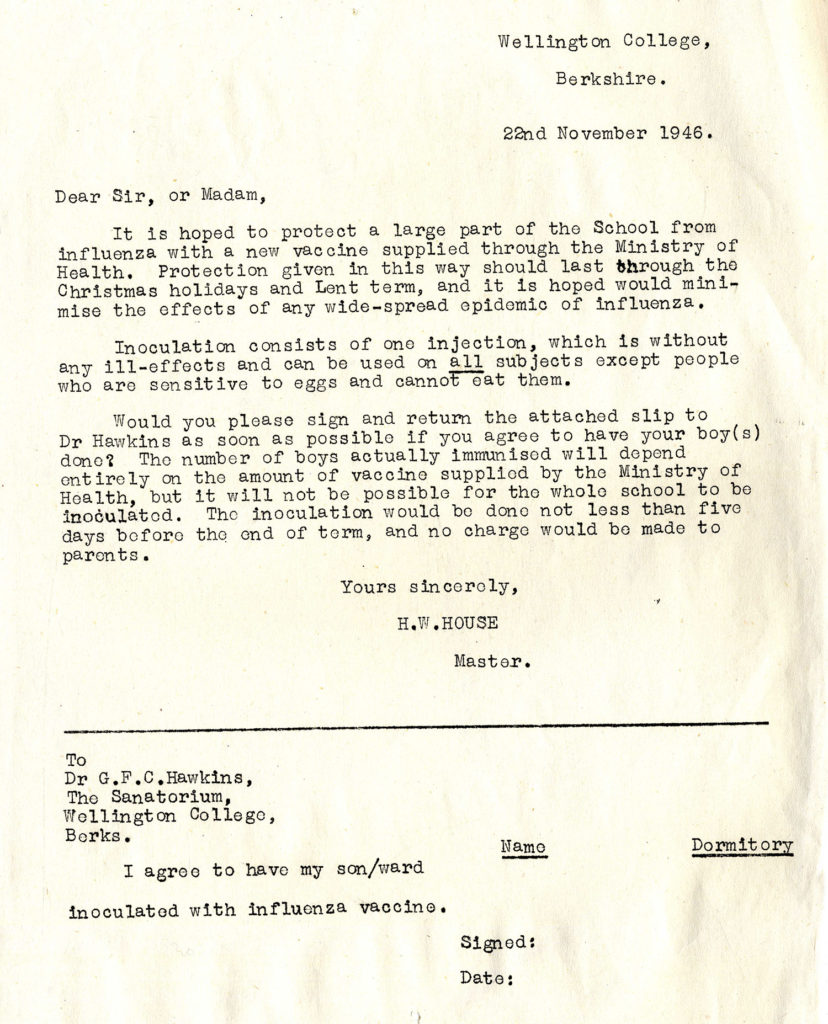

Stuart Dowding (Talbot 1957-61) commented ‘I later learnt that the College doctor, Dr Hawkins, was an early advocate of mass flu vaccination, which speaks a lot for pioneering WC staff.’ The effects of this were also remembered:

‘Once there was a mass vaccination, I cannot remember why but many of us had a bad reaction and had to spend 24 hours in bed.’ Randal Stewart (Anglesey 1953-56)

‘When flu injections were introduced at College, one found one’s arm swelling up and it was quite painful and unpleasant. The jab which my doctor insists I have each year is less than a midge bite by comparison.’ John Green (Talbot 1954-58)

While Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53) experienced unexpected effects from medication:

‘My thumb had got infected by a splinter under the nail. Under a local anaesthetic the doctor extracted the splinter with no trouble. As I left, I was given two pills and was told if the thumb hurt that night, I should take one. I rejoined my group for a Chemistry lesson, and my thumb started to hurt. Assuming that the pill was to reduce the pain, I took a pill. The pain may have gone all right, but I almost fell asleep too. It was a sleeping pill, not a painkilling one!’

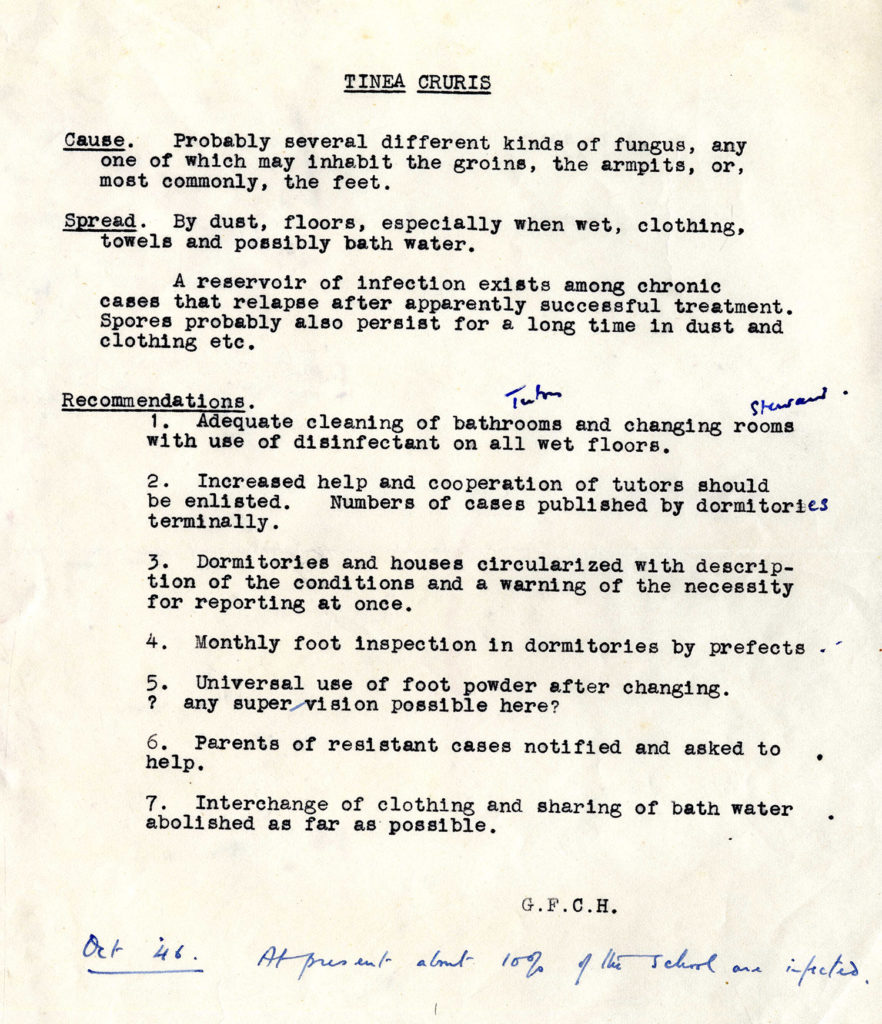

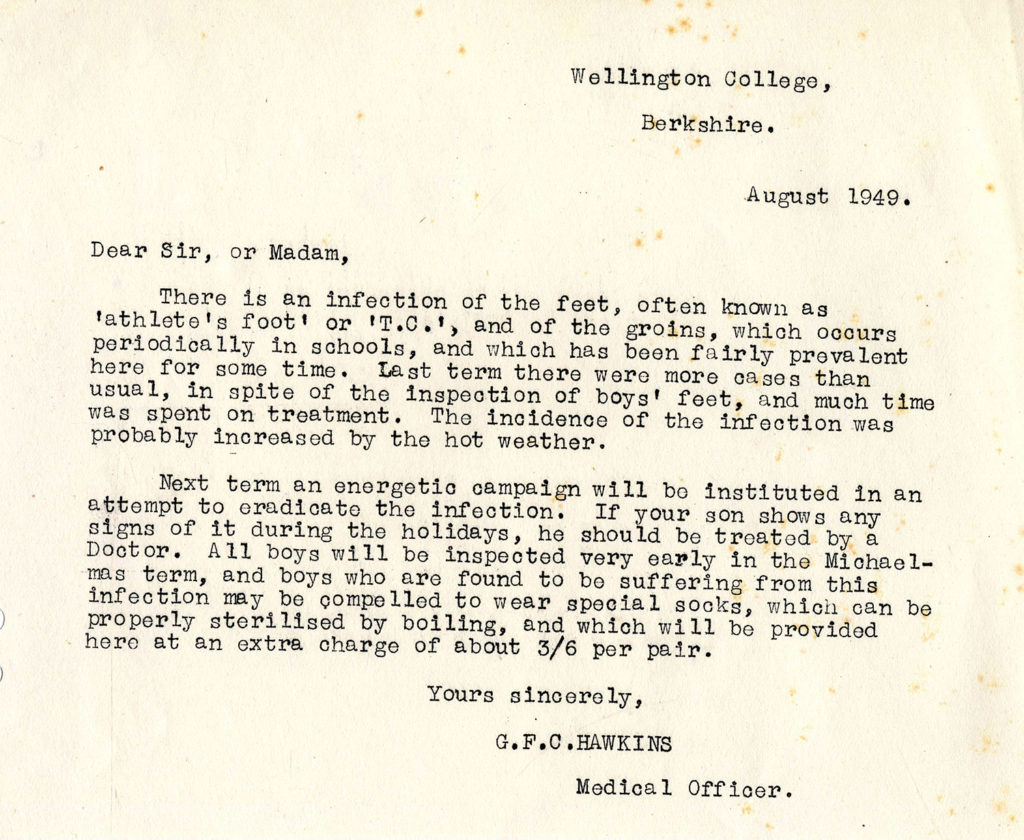

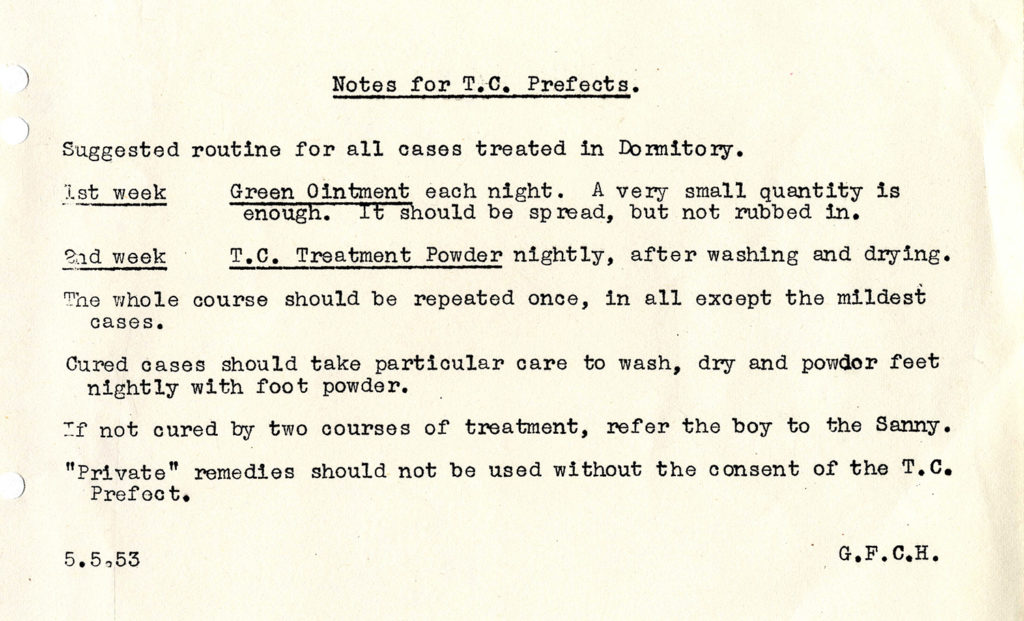

Tinea cruris

But there was one aspect of health care which made by far the greatest impression on our respondents – the termly inspection for tinea cruris or tinea corporis, otherwise known as ringworm:

‘A bizarre ritual that took place at the beginning of each term… Every boy had to line up in front of Matron and lower his trousers and pants, while she sat there with torch and stony face and inspected his nether lands. This was, we understood, for the detection of tinea’. Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘Each term the doctor carried out the TC inspection when every boy was inspected, both toes and crotch, the doctor with his torch saying, “Lift ‘em up, boy!”’

John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘This was oftentimes an occasion for mirth, mainly to cover embarrassment.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘Each boy had to put his feet on a stool and hold open the little toe to reveal whether or not he had athlete’s foot. That was all right, but part two of this procedure was that you had to open your dressing gown (nothing to be worn underneath) so he could inspect your genitals, and, with a spatula, push one’s meat-and-two-veg from side to side to see if there was any infection. He would then sigh “Next” in his bored tone and one could step away, knowing that ordeal was over for another few months! What was even worse was that the Head of Dormitory had to stand beside him, so one could not help revealing one’s most private self to one’s peers, “from whom no secrets are hid.”’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

‘We lined up in the dormitory corridor in shirt tails and bare feet, to be checked for a skin or parasitic disease called TC, which could affect feet and groins. If one was unfortunate enough to have a “groin,” one had to attend sick parade at the Sanatorium for Dr Hawkins to treat the affected area with paint. I remember him sticking his head round the door and calling out “Any more groins?”’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

‘TC was treated with gentian violet, a purple concoction which was liberally applied to the crutch and between the toes.’ Richard Godfrey-Faussett (Anglesey 1946-50)

Malingering

All staff took care to ensure that no student should spend longer in the Sanatorium than necessary. A boy was supposed to get his Tutor’s permission before going there, but some Tutors were more sympathetic than others!

‘One had to get a chit from one’s Tutor to go sick, and “Gaffer” Reese always knew whether the request was genuine or not.’ John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘Hugh Marston: “Why do you need to go to the Sanny – you’re still standing, aren’t you? You can go to the Sanny when you can no longer stand!”’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

However, Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61) recalled that ‘Tutors used to visit their charges, possibly daily, when they were patients.’

The medical staff too were on the look-out for malingerers:

‘It was very comfortable, but the staff made it clear that we stayed no longer than necessary, to make sure that there were no shirkers!’ Anonymous

‘The doctor and nurse were kindness itself, but it was made quite plain after the second night that I was cured and should return to my routine.’

Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52)

The Doctor

Dr Gerald Hawkins was the College Medical Officer, commonly referred to as ‘the quack,’ from 1946 and throughout the 1950s. Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53) described him as ‘no-nonsense.’ Others also remembered his manner:

‘The amiable quack was very laid-back and gave the impression of suspecting everyone to be a malingerer – which on occasion I suspect I was.’

Nikolai Tolstoy-Miloslavsky (Stanley 1949-53)

‘His demeanour was a combination of exhaustion and lack of interest. We always said that if you entered his surgery with your shin bone sticking out and blood all over you, he still would not look up from his desk but, as he always did, simply ask “Yessss?”’ Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58)

The nursing staff

The first Matron remembered by our respondents was Miss Symonds, who held the position from 1922 until 1948. Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47) described her as ‘very stern,’ and David Simonds (Orange 1941-46) said that she ran the Sanatorium ‘with a rod of iron.’ Others also remembered her vividly:

‘My main memory is of the formidable Matron. She wore the miniatures of her Great War medals pinned to her immaculately starched white apron. She must have served in France very early in the War, for the first of the medals was the 1914 Star. I now wish that I had asked her about her experiences.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘The “Sanny” was run by a forbidding elderly spinster called Miss Symonds. Known to us as “Ma Sy,” she had an up-and-down croaky voice, which was easy to imitate. Interestingly, when my father broke his leg as a naval cadet at Dartmouth, he was looked after by a much younger Miss Symonds, and retained fond memories of her.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘“Ma Sy” was in charge of the Sanny, and could be heard saying “Take a pill, boy.”

John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

Miss Symonds was replaced by another rather daunting Matron, Miss Hall. John Thorneycroft (Benson 1953-58) called her ‘formidable’ and considered that ‘it was not advisable to cross her.’ She could, however, be more lenient:

‘Miss Hall was a rather grand lady, previously a “Dame” at one of Eton’s Houses, and, to my dismay, one night to be encountered in the same train compartment as my partner of the previous night’s dance, whom I had conspiratorially planned to meet by boarding the train at Sandhurst which was carrying her to Guildford. With admirable sensitivity Miss Hall moved to another compartment and, my fate clearly in her hands, never reported me.’ Christopher Capron (Benson 1949-54)

Miss Hall in her turn was replaced in 1957 by Miss Attenborough, who, according to Robin Ballard (Orange 1955-59) ‘had a small white dog call Snow Bumble.’

The Matrons were assisted by a number of nurses, generally noticeably younger. Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47) recalled ‘a delightful young nurse who somehow managed to keep the younger masters at arm’s length!’ John Flinn (Combermere 1944-49) thought that the Sanatorium was ‘rather popular on account of two pretty nurses, “Heart Throb” and “Twinkletoes,”’ while Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58) remembered ‘the special nurse who really looked after me, the lovely Irish Nurse Quinlan.’

Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56) also remembered a particular nurse:

‘The experience was greatly improved by the attention of a little, bubbly Australian nurse who cannot have been a great deal older than some of us. Obsessed with that question which seems to interest all nurses, she would visit every bed each morning to ask the inevitable question. In no time at all she became known to us boys as “Bowels Dearie?”’

Fellow patients

A few respondents sent in rather unusual stories of their fellow patients in the San:

‘I was put into a bed next to someone who snored so strongly that, during the night, I opted to go to another ward. This caused concern for the staff who, on discovering the empty bed the following morning, raised the alarm!’ Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60)

‘I shared a room with another boy, who will remain nameless. He was a very odd fellow who used to think he could fly, and I sometimes found him drinking his own urine from the pot beneath his bed. Other than that, he was quite a nice chap!’

Anonymous

‘I was in the Sanatorium for chicken pox with Haile Selassie’s son, Prince Makonen, in the next bed. He was seventeen and had just been given a harem at home. Asked what it was like, he put his thumb in his mouth and made a popping noise… My suspicion is he had not been allowed to penetrate any of these ladies, but you never know.’ John de Grey (Blucher 1938-43)

Catching up on work

Our OWs had varying experiences of trying to keep up with schoolwork during illness:

‘I did miss school, and there was no attempt by my Housemaster to see what I had missed and whether this mattered.’

David Nalder (Orange 1949-53)

‘During my “O” Level exams I had a very severe dose of sinusitis. As a result, I took the exams from my bed in a private ward. Not unpredictably I only passed three subjects, setting me back as I had to wait another year to complete them.’ Richard Craven (Hill 1950-54)

‘I spent several weeks in the Sanatorium with jaundice, was well looked after, and convalesced with Teach-Yourself books which enabled me to do well in School Certificate.’ Sam Osmond (Hill 1946-51)

Comfort

Overall, our respondents returned an overwhelmingly positive view of the Sanatorium and its staff. ‘Clean,’ ‘efficient,’ ‘comfortable’ and ‘civilised’ were words which occurred again and again in their descriptions.

By necessity, Sanatorium occupants were isolated from their friends, which is perhaps why Nick Harding (Combermere 1951-1955) described the experience as ‘comfortable but dull,’ and Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53) found it ‘quiet and a bit lonely.’ Generally, though, memories were better:

‘Admission to the Sanatorium was a friendly and comfortable experience, and an agreeable break from classes.’ Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53)

‘Always happy memories of being out of school for a while, well looked after and fed, and a chance to lie in bed and listen to the radio!’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

‘A lovely experience, good food, a radio and lovely nurses.’

John Ravenhill (Orange 1953-56)