CCF: Specialist Sections

All those joining the CCF had to do a certain amount of time in the Army Section before they were given the option to join one of the other sections. Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952-57) later joined the Naval Section, but considered that “the preliminaries in the Army Section were not wholly useless, I remember some of the jingles such as ‘shape, shine, shadow, silhouette…’”

The Army Section

Some elected to stay in the Army Section, and did not regret their decision:

‘I joined the Army branch; my rifle number was 171 in the Armoury. We were taught how to use and clean the rifle and the Bren gun, having competitions with other platoons, and then went on a Field Day with Charterhouse or other nearby CCF units which was always exciting. We learnt how to do platoon in the attack, dig trenches and many other things which became very useful in Basic Training when I was called up.’ Anonymous

‘I joined the Army Contingent and was issued with battledress, boots and webbing and we had a certain amount of fun playing in the woods and also having Field Days down on the Aldershot training areas where we used blanks and thunderflashes. On one exercise, we had run out of blanks and when we charged the enemy position, our officer, Captain Comber used to shout “Bullets!” – from then on he was known as “Bullets” Comber! The CCF used to have an annual inspection by some senior visiting officer; on one inspection just as the officer was passing, a cadet called Tim Thompson was suddenly sick all over him – end of inspection – hurray!’ Leslie Bond (Lynedoch 1948-53)

Others enjoyed the specialised Artillery section:

‘In my last year, the College obtained a 25-pounder field gun and I was the first cadet sergeant to be in charge of it. The gunnery I learnt was of great benefit to me when I eventually joined the Royal Artillery.’

John Hoblyn (Hardinge 1945-50)

‘We had a thriving Royal Artillery section with our own 25-pounder gun, limber and “Quad” gun tractor. I really enjoyed my time as leader of the CCF Royal Artillery Section. I was soon to be the fourth generation of Royal Artillery Officers in my family, so this was Utopia.’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘As it seemed more entertaining, I joined a small Royal Artillery Section, run by the regular Army, who came with a 25-pound mobile gun, towed by a military vehicle. We had great fun being driven into mock action, with me standing with my head through a hole in the vehicle’s roof giving instructions to the driver, and then going through the full drill of targeting and firing the gun.’ Anthony Bruce (Benson 1951-56)

Later, the Signals Section was an option:

‘For some reason I ended up in the Signals Section (possibly to avoid having to carry a Bren gun), and had to master the dreaded ‘88’ set radio. This had four channels, two of which were totally forbidden, as they matched the ITV channel, and anything said was broadcast over the local area – in the afternoon, often horse-racing. The temptations were enormous…’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

The Naval Section was generally reputed to offer the best trips, but Army section trips could be interesting too:

‘There was a trip to Bovington, HQ of the Royal Tank Regiment, where we were warmly welcomed by “The Tankies” and given first-hand experience of travelling over the proving grounds in several models of tank! My father served in the 44th Royal Tank Regiment throughout WW2 until he was mortally wounded a month before VE Day; it gave me a stark realisation of the conditions under which he and his brave companions had fought!’ Jeremy Watkins (Blucher 1951-55)

‘…in 1955 to Osnabruck with about 40 others as guests of the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry, BAOR. I was the most senior cadet… An equivalent visit the previous year had been to the Black Watch who had treated the cadets royally, but our visit was largely uneventful apart from a visit to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp which was then almost as it had been when discovered at the end of the war, with mountainous mass graves etc.’ Nick Harding (Combermere 1951-1955)

Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58) also remembered this trip:

‘I went to Germany in 1954 with the Corps and we stayed in palatial German barracks which amazed us by having central heating. We learned a lot of swear words from the other ranks of our host regiment The Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Infantry (“Beds and Tarts” to us), and we had some enjoyable tourism, notably to Hamelin and Hamburg where we saw Madame Butterfly in a converted cinema because the opera house was still rubble. We also were taken to Belsen concentration camp, liberated only nine years previously. This was very salutary, most of us never really having heard much of the camps. It was nearly dusk as we arrived and it was noticeable that there were no birds in this bleak place. The coach was silent after that visit.’

The Naval Section

Many of our respondents chose to join the Naval Section of the CCF, which started in 1948.

For some this was because of family tradition, a desire to join the Navy after school, or simply to learn new things:

‘My ambition then was to join the Navy, and when a Navy Section was started, I joined. Looking back, the standard of training was good and many outside visits, to ships, sail training camps in holidays, and other establishments, were arranged. We were enthusiastic about all this and took it seriously.’ Richard Godfrey-Faussett (Anglesey 1946-50)

‘I opted to join the Naval Section and I can safely say that I very much enjoyed the experience. There was quite a bit of drill (square bashing) and Lieutenant Charles Kuper, the master in charge, was a great character. I can recall marching up and down the Kilometre, all of us singing Hearts of Oak at the top of our voices, the idea being that this would be a substitute for a full Royal Marine band!’ Colin Mackinnon (Hardinge 1951-56)

‘I chose to move to the Naval Section where there was a certain amount for me to learn that was not familiar, and the opportunities for gaining experience at sea or at land-based Royal Navy establishments were a great attraction to me.’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954-59)

‘My father was in the Royal Navy and so, with the idea of possibly following in his footsteps, I joined the Naval Section. We spent Wednesday afternoons learning such arts as morse, semaphore, rope work, how to rig a whaler, and doing a great deal of drilling in one of the school quads.’ Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

William Shine (Hill 1956-60), by contrast, ‘chose the Navy as I liked the uniform.’ Likewise, Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53) ‘valued learning how to maintain the “bluejacket” uniform of the RN Section; washing and ironing the colour running collar, rolling up and pressing old style bellbottoms. But Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953-58) considered that, ‘to me, the least attractive side of it was the coarse uniform which scratched the skin mercilessly and necessitated the wearing of pyjamas underneath!’

But the greatest attraction of the Naval Section was the opportunities for travel and adventure which it offered, as some respondents explained:

‘After the first year I changed to the Naval Section because it had much better Field Days, namely taking a train to Portsmouth – an opportunity to virtually chain-smoke – followed by a day at sea, generally on a minesweeper, and another smoking journey on return!’ William Young (Anglesey 1954-58)

‘The advantage of the Naval Section was that Field Days consisted not of slogging about on the heath with rifle and blanks in ignorance of the tactical plan being rehearsed, but of visiting Portsmouth by train and seeing HMS Dolphin or Vernon, which were new and interesting.’

Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952-57)

Numerous OWs recounted the various Naval trips they had been on:

‘In the summer of 1949, the summer “camp” was to spend two weeks on board the cruiser HMS Superb at Chatham. To describe that experience would require several pages, but I can say that it provided me with several growing-up experiences. I went home by bus at the end of the fortnight and my mother was horrified at the state of my clothing – we hadn’t done any washing of our clothes throughout the whole fortnight, and I suspect that not only my clothes, but my body required scrubbing!’ Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948-1950)

‘”Camps” and termly Field Days were visits to HM ships (Duke of York, battleship in Portsmouth; Romola, fleet minesweeper) for a week; and flying in Tiger Moth light aircraft at Royal Naval Air Station, Culham. Inevitable visits to Excellent (Whale Island gunnery school); Vernon (torpedo & anti-submarine), and other Naval establishments around Portsmouth.’ Tim Reeder (Picton 1949-53)

‘We flew in naval aircraft from Yeovilton, went out in RAF air-sea rescue boats from Calshot, but the best of all was a 2-week trip during the summer holidays in HMS Trafalgar, a Battle Class destroyer. Leaving from Portsmouth we visited the Orkneys and Shetlands before crossing the North Sea to Bergen in Norway where we stayed for a couple of days before returning home. We stood proper sea watches and worked part-of-ship and this, together with Charlie [Kuper]’s other training initiatives, were of tremendous value to those of us who eventually served in the Royal Navy.’ Anonymous

‘I remember a couple of camps, one to HMS St Vincent, the Navy’s boys’ training establishment, and one on HMS Boxer, then in dry dock in Portsmouth. One memory of the latter is the young Leading Seaman detailed to look after us explaining in vivid (pungent?) lower deck/barrack room language that there was no fresh water on the ship because someone had contaminated the fresh water tank. Afterwards, we all went round repeating his exact words with great glee! Also, the odd Field Day spent on ships in Portsmouth attempting to sleep in hammocks – thuds throughout the night as some unfortunate fell out or his knots undid!’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

‘On one occasion, virtually the whole Naval Section was transported to Gibraltar from Portsmouth aboard the cruiser HMS Birmingham. In Gibraltar we were looked after by the Governor, who happened to be an Old Wellingtonian, and we were feted right royally. Returning to the UK, we were all split up and came home on various ships. I was drafted to HMS Loch Insh, a frigate. It took us five days to get back to Portsmouth and I can recall that most of that time I had a paintbrush in my hand and was painting everything “Battleship Grey.”’ Colin Mackinnon (Hardinge 1951-56)

‘We visited Portsmouth on several occasions, went to Gibraltar in HMS Vigo a destroyer, and went on an exercise in a submarine that was under attack from depth charges. All much more fun than roughing it at Catterick which the Army cadets had to endure.’ Nigel Hamley (Hill 1952-55)

‘Occasionally we were taken down to Portsmouth to fire anti-aircraft guns, including in a “battle trainer” when gallons of water were thrown over us as we loaded and fired. In early 1957 I joined a party of cadets at the naval dockyard of Rosyth on the Forth. We were given what was my first flight, over the Forth Bridge, and also passed beneath it in a small minesweeper.’ Anthony Goodenough (Stanley 1954-59)

‘The best was a week’s summer camp with Charlie Kuper, sailing a Navy cutter from Portsmouth on the Solent, camping each evening on a beach.’

Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954-57)

‘I was delighted to get the opportunity to join a contingent from Wellington who spent a week on board the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle, during sea trials off the south coast of England after a major refit in Plymouth. This was like heaven to me. We paraded with the crew on formal occasions and slept in hammocks where we were woken by a loud call by a regular seaman, “Wakey, wakey, rise and shine. You’ve had your time – now I’ll have mine,” and if you did not react immediately, a wallop to the underside of the hammock was administered with a wooden baton! Another vivid memory was that we had to paint the flight deck with grey paint whilst the ship was carrying out speed trials over the measured mile somewhere off Dorset. The paint brush was more like a mop which one dipped into a tub of paint, then slapped the paint onto the deck. Fortunately, I was near the front of the flight deck, as some paint flew off the mop in the strong wind, so those who were further back suffered a covering of spots of paint on their overalls!

The following year, we had the opportunity to sail across the Atlantic to the West Indies in a destroyer which was a really exciting prospect. However, just before we were due to sail, this was cancelled because the ship had to relocate to the Mediterranean as the Suez Crisis had arisen, so we were sent to Rosyth Barracks with a number of other schools where there was a very competitive atmosphere between the schools, principally of an anti-social nature! The only memory I treasured of this trip to Scotland was the fact that we crossed the Forth Bridge in the train early in the day of arrival, then flew over the bridge that morning in a DH Dove and then sailed under that bridge in a destroyer that afternoon and then at speed along the Firth of Forth.’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954-59)

‘Field Days were usually great fun at Portsmouth – on board HMS Excellent, firing Bofors, flights in a De Havilland Dove (from Lee-on-Solent HMS Daedalus) and trips in a sub among others. Camp in Scotland along the Caledonian Canal was also enjoyable, except for my shipmates (who for some reason objected to having eat my custard with a sharp knife and fork) and being seasick in the Firth of Forth – but Dick Borradaile told me how to avoid it and it has worked ever since.’ Stuart Dowding (Talbot 1957-61)

Norman Tyler (Hill 1947-52) claimed to be ‘one of the original members of the Royal Marines Section,’ but this is not mentioned as a separate entity in the school records. Nevertheless, some boys were very keen that this would be their future career path:

‘A boy called “Squealer” Mathews and I went on a Schools Entry Course to Royal Marine Barracks, Lympstone, for a summer commando course in order to make sure we joined the Marines for our two years’ soldiering. We came back to Wellington with our smart Royal Marine uniforms. When a Colonel of RM was taking the parade on South Front, we were appointed his special guard of honour. After standing for some time in the sun wearing a tight hat I felt dizzy. I knew one should look as though part of the parade so set off to march off. Unfortunately I marched round in tight circles and fainted! Not the best start to my military career.’ Peter Cullinan (Benson 1948-52)

The RAF Section

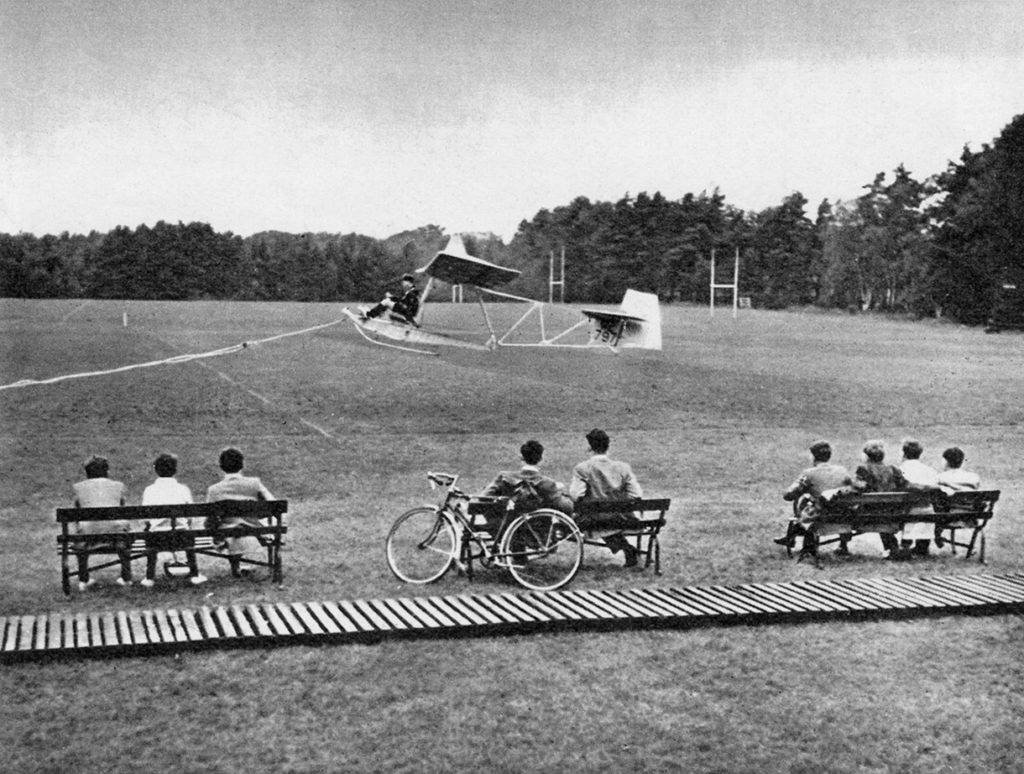

The Air Section of the Corps existed throughout the 1940s and 50s, although as the Year Book for 1958 recorded, its members were never numerous.

Perhaps the other Sections looked down on them, judging by Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)’s memorable if somewhat tongue-in-cheek description of them as ‘a few effete shoe-wearing individuals.’

Nevertheless, those who took part had good memories of their experiences:

‘I was a member of the Royal Air Force section, and lucky to be given the opportunity to have gliding lessons.’ Robert Wilkinson (Anglesey 1947-50)

‘The RAF Section was able to utilise the college glider, which accommodated one cadet at a time. It was launched by means of a giant catapult, the elastic of which would be stretched out by teams of other cadets, in a “V” formation.’ Richard May-Hill (Hopetoun 1957-61)

‘I enjoyed flying in Tiger Moths from Woodley Aerodrome.’ Ambrose Spong (Stanley 1950-51)

‘When Army cadets conducted battle exercises in the field, Air cadets were sometimes flown in Tiger Moth biplanes acting as enemy aircraft. It was surprising how menacing a Tiger Moth appeared to be when diving straight at you!’ Peter Rickards (Murray 1947-52)

‘The RAF Section also had great camps. I got free flying training at RAF Kidlington in Chipmunks and then at South Cerney in Provosts.’

Graham Stephenson (Combermere 1953-57)

‘Those memories I have of our general College Corps activities are outshone by a vivid memory of a flight in one of the last RAF flying boats, the Sunderland. On this trip it happened to be my turn to visit the cockpit and talk to the pilot just as we were approaching the Needles. We were probably only at about 1000 ft and I could see them quite clearly. “Are those the Needles?” I said – “Yes,” said the pilot, “let’s go and look at them” – and promptly executed a turn and dive which, even in my inexperience, was somewhat volatile. While in consequence observing the Needles from about 50 ft above the water, he did admit that he had just come back from a re-training course on light aircraft and he had been rather over-enthusiastic on his approach. During the later landing at Southampton Water, I was standing on the hull of the craft and discovered that the impact on the water pushed the hull deep enough to be able to see passing fishes through the portholes and then the wonderful sweep of water from the wake as the aircraft rose to the surface and taxied to its mooring.’ John Berger (Benson 1949-52)

‘On a field trip to RAF Odiham, an officer explained that a Gannet aircraft was shortly leaving for Bonn to deliver some urgent documents. The rear cockpit which housed the radar and weapons operator would be empty, and if one of the boys would like to go for the return trip, he would be most welcome. It was Michael who was chosen, and who disappeared in a roar of contra-rotating propellors, expecting to be back by teatime. On arrival in Bonn, the Gannet was diverted to Malta bearing the unfortunate Michael. It returned to England bearing not Michael but a senior RAF officer. Michael was in Malta for nearly a week before he could be flown home. He was royally entertained by the RAF in the meantime. Poor Harry House had to telephone Michael’s mother to explain why her son was not at Wellington but in Malta!’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

The Corps Band

Those with the inclination and some musical talent could find their way into the Corps Band, which entailed special responsibilities and uniforms.

For some, this was a source of enjoyment and pride:

‘I remember playing Reveille and Retreat at a Corps camp… Two of us also played the Last Post at a nearby village, I played by the church door while the other chap played a few seconds after me from about fifty feet away ago as to produce an “echo” effect.’ Christopher Beeton (Talbot 1943-47)

‘I enjoyed the Corps, became a bugler and played the B-flat fife. I then grabbed the chance to don a leopardskin and carry the tenor drum – a great chance to show off – and became quite expert at twirling the drumsticks.’ Randal Stewart (Anglesey 1953-56)

‘Finally, I served a couple of years in the CCF Band where I played the fife. I loved this very special experience as I had been brought up in an environment where marching to military music was in my blood, and I was thrilled to be on parade on special occasions in my smart naval uniform. This was the “cream on the cake” for me as far as Wellington College and the CCF was concerned.’ Tony Glyn-Jones (Picton 1954-59)

Others had more comical memories:

‘The dormitory gas ring was used to heat two flat irons which were only used by Corps buffs to press their uniforms on the eve of major inspections. As the bass drummer in the Corps Band, most of my uniform was covered by a tiger skin and other gaudy embellishments, so I seldom pressed my kit. However, before one such inspection, someone stuck his hand between my legs and tugged my tiger’s tail. The tip came away in his fingers. I managed to sew it on again in time, but back-to-front. Luckily no-one inspecting me and my imposing rig from the front noticed the absence of tawny spots on the tail’s last six inches.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59) sent in this description of an occasion captured in the accompanying photographs from the Year Book:

‘I was a drummer in the Band and I was the leader… There had been a special Centenary parade at the Duke of Wellington’s house, Stratfield Saye, where my band played marching back and forth along the lower of three terraces in front of the grand house while the Duke, the Master and “Hosch” Roy sat on the top terrace. Having finished our little concert, I was to march smartly up the long steps to salute the Duke and ask permission to fall out. I was doing splendidly until the very last step where I tripped and fell flat on my face at the feet of the Duke. The Duke was very cheery, but “Hosch’s” face was twisted with disgust.’