Teachers: Classics and Languages

The Classics were an essential part of a public school education in the 1950s, and Wellington College was no exception.

Like most other subjects, Latin was taught in a very traditional way, which in retrospect, some of our respondents felt had been unhelpful:

‘While we boys were turning to stone under a blizzard of datives and ablatives and the dreaded ablative absolute, poor old Caesar endlessly pitched camp having marched ten miles. We learnt nothing of the importance of Rome or the significance of Roman history to the present day, just grammar. I am distinguished by a Latin report which reads: “Ryall, Latin. This boy is an unclassical ass!” You hit the nail on the head, Mr Wright.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

‘The usher tried hard to teach us, tapping us on the head with a broken billiard cue when declining Latin verbs.’ Peter Davison (Beresford 1948-52)

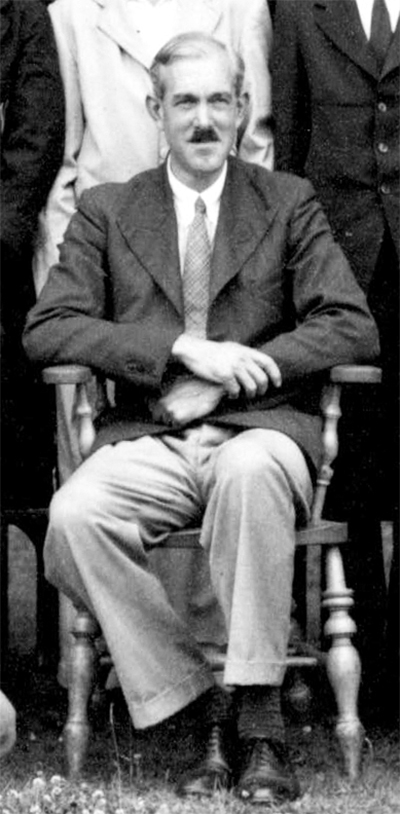

In the 40s and early 50s, the senior Classics teacher at Wellington was Herbert ‘Titch’ Wright, a man who made a strong impression on many:

‘He ruled with the proverbial rod of iron and woe betide any boy who hadn’t done his prep or made some stupid mistake. A teacher of the old school, dealing in fear and not going out of his way to be liked.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

‘He was a master of grammar and syntax and made sure you learnt them.’

Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘Titch was very tall and somewhat daunting, and his great cry was “Parse,” which was the cause of tears occasionally for those who failed.’ ‘Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

‘In my first lesson with the 6 ft 2 in “Titch” Wright, he got down the register for the class, looked up to see who Berger was and said “Ah – I beat your father on his first day – I hope I don’t have to do the same to you.” I managed “So do I, Sir” in a very small voice and it seemed to pass muster.’ John Berger (Benson 1949-52)

‘Mr Wright made the fatal mistake of not explaining to me why we should all use the continental pronunciation of Latin instead of the (now clearly ridiculous) English pronunciation that I had grown up with, and for which he mocked and castigated me.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

Some had better memories, as Mr Wright introduced them to a lighter side of the Classics:

‘He delighted us with silly classical puns and risqué homophones … in the pronunciation we were taught, “At least having heard” in Greek sounded just like “He kissed a cow’s arse.”’ Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947-51)

‘H S Wright was taking us as a stand-in – he certainly wasn’t our regular teacher – and he introduced us to a piece of macaronic verse – the Bankolidaiad, which even then I thought very funny, and still do today; I now appreciate not only how funny it is, but how clever it is, both in the content and in its Latin versification (I can, in fact, recite most of it from memory still)’ Alastair Wilson (Talbot 1948-1950)

Other Classics teachers included ‘Archie’ Seaton, ‘with a talent for acting in revue’, and according to Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56) ‘a strange cove… he always asked for marks to be given to him in Latin. “Mihi numeros date,” he would say. It was the same when we were being taught Greek – the request still came in Latin.’

And subsequent 8th Master of Wellington, ‘Gus’ Stainforth:

‘I hated the subject, could arouse no love for the Romans and had no wish to learn their language… Gus Stainforth ruled his classes with a somewhat dry insistence on accuracy and dedication to his beloved Latin tongue. There was little if any humour in his style of teaching. Most of us were frightened to various extents by the threat of having to stand up and show our ignorance in front of the class. I don’t think that Stainforth set out to humiliate boys, he just had very high standards which he was determined should not be sullied by sloppy work.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

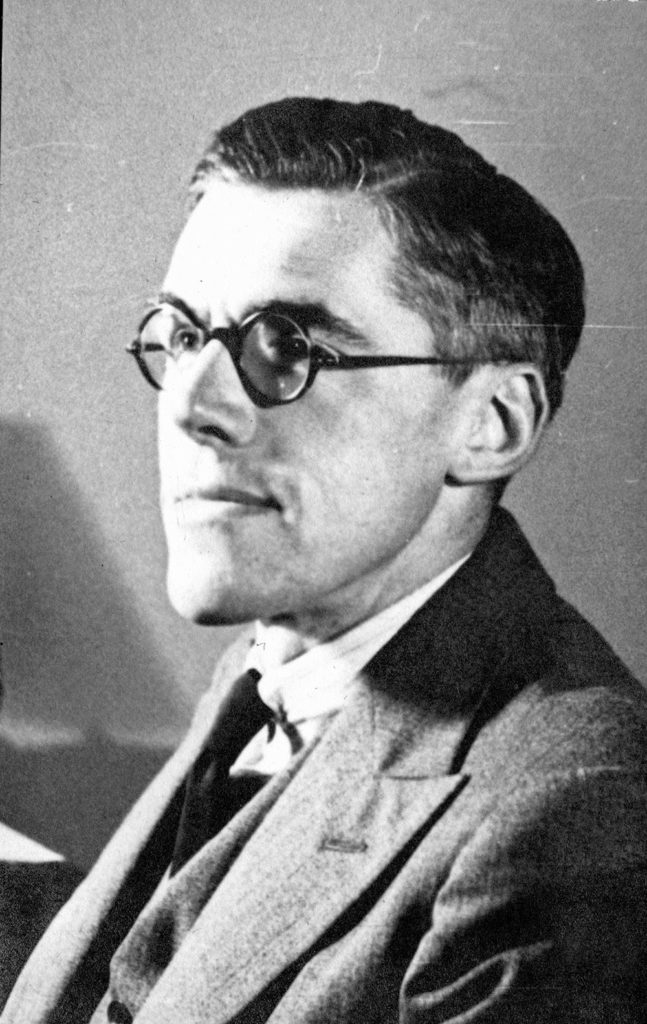

Alan Ker, by contrast, seemed much more popular:

‘During my whole school career, I hated all my Latin teachers except for the very first at my prep school and the very last, Mr Ker at Wellington, who, with private tuition after my fourth failure to pass the School Certificate exam, managed to achieve success with me at the fifth attempt.’ Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51)

‘Alan Ker taught the Classical Sixth. He was a don rather than a schoolmaster… His teaching of Horace and Vergil gave me a real love of their poetry. Also, in the summer, he would sometimes take us down to the garden of his house on Back Drive and we would read Homer under the cherry tree. We would also enact impromptu scenes from Greek plays on Rockies. He was a great English teacher too, and introduced us to some of his favourite authors, among them A E Housman, E M Forster and the South African poet Roy Campbell.’ Christopher Stephenson (Hill 1949-54)

‘Alan Ker, an ex-Brasenose don, was an inspiring teacher. Once a week, he would take a group of us for extra tuition in his house down Back Drive, sometimes including some really disgusting Martial epigrams … huge fun. His wife brought us cocoa; I don’t think she realised what we were up to.’ Murray Glover (Anglesey 1947-51)

‘My principal Classics teacher in the Lower Sixth was Alan Ker, the most donnish of those on the staff at Wellington. He seemed incapable of believing that those he was teaching could make mistakes that might be classified as howlers. Instead, he searched his mind for what the pupil might have been trying to say. It could be a flattering way out after a crass error.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

Not as intellectual, but equally liked, was Mr Aglen:

‘‘Fatty’ Aglen attempted to teach me Latin – remarkably patient with my lazy and uninterested approach to the subject.’ Charles Ward (Hopetoun 1951-55)

‘Most of the teachers were critical of my effort and scathing of my ability, with the exception of Mr Aglen, who alone made the subject (Latin) interesting to me. No-one else inspired or encouraged me…’

Anthony Collett (Combermere 1953-58)

‘Tubby Aglen, who taught me Latin, and one of whose lessons followed PE, from which we were always let out late. This regularly resulted in 100 lines – ‘Better late than never, better never late!’ I arrived late for one of his lessons, and handed over my previously-prepared lines the instant the words passed his lips. I always thought that the resultant multiplication of lines was rather unjust.’ Michael Peck (Anglesey 1954-59)

‘Aglen strove to keep control of his classes and just about succeeded… I well recall the time when the school was subjected to an inspection. Aglen was instantly transformed into a nervous mumbling schoolboy who had not really done his prep. We were studying some verse by Horace or Ovid – whichever of the two it was, Aglen muddled them up. “So what Horace is trying to say here…?” he intoned, as we all knew he should have been saying Ovid. So far from tipping him the wink, we let him plough on getting ever deeper into the mire. Years later, I recalled the moment with dear Aglen who remembered it vividly and said, “And you all sat there with no-one helping me out!” Very true!’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

In the later 1950s, some encountered George Macmillan, ‘blessed with a perfect memory which enabled him to teach and correct translations without being able to read owing to a congenital eye condition. George took me on my first and memorable visit to Greece in 1957…’ Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952-57)

‘When uncertain of anything, Sandy Entwisle would say he would consult the oracle. That meant the much more brilliant George Macmillan.’ Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56)

French and German

As with Latin, some Wellingtonians felt that the teaching of Modern Languages was rather dry:

‘Language teaching dwelt relentlessly on grammar: the present tense, the past tense, the future tense, the pluperfect and the dreaded subjunctive, and at the end of all this we were unable to speal a word of it.’ Roger Ryall (Picton 1951-56)

Those at Wellington in the 1940s did have the advantage of being taught by native speakers, but may not have really appreciated it:

‘M. Noblet was a Frenchman who taught us his native language. He struck us as a sad old gentleman. He had left his wife in occupied France, and suffered from shellshock from his service in the Great War. Perhaps to alleviate these troubles, he almost certainly drank too much. We, insensible rabble, played on his shortcomings, adding to his miseries. Nevertheless, he taught French well. He had written a book of French vocabulary, which consisted of each page given to words connected to some specific place or action – for instance, the kitchen, the drawing room, the railway station, the shop, etc. Our prep was usually to learn the words on a single page. By this means, I found that I acquired quite a good working vocabulary, so then with a basic knowledge of French grammar, I was able to carry out a conversation.’ Hugo White (Hardinge 1944-48)

‘Monsieur Albert Noblet, Legion d’Honneur, our French master, a Laureate of the Academie Francaise, who was wont to drown his sorrows in whisky after school at The Wellington Arms. The boys invented a game as to how far away they could smell his approach, and sometimes locked him out of the form room. One of his favourite expressions in class was “You are a lounge lizard – lean off that wall!”’ Peter Bell (Blücher 1943-48)

‘Our German master, Mr Braunholz, was a pleasant elderly, but vulnerable, man whose nickname was “Bakelite Bottom” on the grounds that he could and would sit on upturned drawing pins with no apparent discomfort or even realisation of their presence. Very unkindly, we would resort to other annoying activity. One concerned the spring door-shutting device, the strength of which was adjustable. Slowly, day by day, we made it very slightly harder for him to open until finally he had to put his shoulder to it. At that point we turned it off altogether and he came bursting in knocking his desk over on the other side of the room. It was his nature not to ask who was responsible.’ Anonymous

‘On one memorable occasion the boys put tin-tacks on Mr Braunholz’s chair. He came in and sat down quite unconcerned. When the boys began giggling, he told them that it was quite all right as his backside had been blown off in the Great War and he had a tin one… This may well have been true, as he joined the staff at Wellington in 1918.’ Peter Bell (Blücher 1943-48)

‘To Mr Braunholz’s French class. Entry proved impossible. Yet again, his key could not unlock the door. We waited about, joshing. Arrived a carpenter from the Works Department, removing the blockage, normally chewed paper or gum, inserted by one of us in strict rotation the night before, he threw open the door and we filed in for the few remaining minutes of our lesson.’ Robert Waight (Orange 1942-46)

‘Our teacher in German, Mr Braunholz… We once dressed up as College workmen and removed all his furniture while he was in the middle of a lesson. However, he must have been of some good, because I went on to become an unofficial interpreter to my Colonel in my regiment in Germany.’ Richard Godfrey-Faussett (Anglesey 1946-50)

Another Languages teacher of the 1940s was Mr Thew, who according to Peter Gardner (Hardinge 1946-51) ‘was unique in his imprecision when handing out ‘impots’: “Pirie, take rather more than five hundred lines.”’ Mr Thew was only at Wellington for six years, but most of his colleagues in the Modern Languages department clocked up service to the school of thirty or forty years. Among them was Rupert Horsley, at College from 1929 until 1966. Bertram Rope (Picton 1949-54) recalls having the difference between “’Avoir to Have’ and ‘Être to Be’” literally beaten into him by Mr Horsley, but nevertheless wrote, “he was a very good Tutor and I was very fond of him.’ Another long-timer was Mr Storrar:

‘I enjoyed French and German, taught by Messrs Storrar and Herring, for A Level. I also remember singing German songs.’ Anonymous

‘I studied Modern Languages and loved Bob Storrar’s classes. Bill Brown was excellent too.’

David Simonds (Orange 1941-46)

‘I really enjoyed being taught by Mr Storrar with his Wagnerian bass. Neighbouring classes complained about the volume of our mainly hunting (Jagd) songs. Led by his booming bass we sang “Die Schnepf’ in Zig Zag zuge treff ich im Sicherheit”. He read us the classics, poetry and stories in his deep and menacing voice.’ Johann Burgstaller’s Photographisches Apparat still haunts me.’ Pat Stacpoole (Combermere 1944-48)

But the teacher whom most remembered was Peter Hincks.

Some did not take to him; Martin Kinna (Murray 1953-58) describes him as ‘not a natural teacher,’ and some objected to his methods of punishment:

‘The master I fell out with was Hincks… he would hand out unreasonable punishments for the most minor offences. His favourite was to inflict copying out pages 100 and 101 of the French grammar textbook, and every accent and punctuation mark had to be correct or you had to do it again. I got to the point where I refused to do it and he kept doubling the punishment, but I still refused to do it and the end of term put an end to the issue, as I was in a different class the next term.’ Graeme Shelford (Hardinge 1954-57)

‘He instilled fear by his mere presence – augmented by liberal use of a ruler! Any misdemeanor or grammatical inexactitude drew the senseless punishment of writing a thousand repetitive lines for prep.’ Henry Beverley (Anglesey 1949-53)

But others liked or respected him, not least for his athletic record and physical presence:

‘Peter Hincks was a really big man in every way and much enjoyed by all.’ ‘Bobby’ Baddeley (Picton 1948-52)

‘His endearing habit was to say, as he handed out test papers: “with the compliments of the management!”’

Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951-55)

‘Peter Hinks made a strong impression, in part because of his sheer physical presence, a pipe-smoking barrel-chested man with broad shoulders. He was one of those people who despite a rather soft voice had no need to be vocally assertive to be in complete control. I think we respected him for his unflappable manner. As an aspiring shot putter, I revered him for his success as the UK national shotput champion.’ Michael Mathew (Murray 1956-60)

‘He had been a shot putter at university, and had once gone to the US with a British university team to compete against a joint Yale-Harvard team. He told us that one day when he went out to practice, he discovered to his horror that the shot impact dents left by the Americans were several feet beyond his personal best. He thought that all was lost. However, he beat the Americans with ease. Later, his America competitors told him that they had just made these dents earlier in the week in an attempt to psych him out!’ Chris Heath (Beresford 1948-53)

After the war, a cohort of younger teachers arrived, as recalled by Alan Munro (Talbot 1948-53):

‘Two ushers who encouraged a spirit of intellectual enquiry and stimulated my interest in foreign languages and literature were Douglas Young and Peter Willey.’

‘I started German with Peter Willey, my favourite teacher. He instigated a polyglot choral society, and we sang folk songs, drinking songs, popular songs etc.: very good for the memory and pronunciation. I also went with him and others to Hochkrumbach, a big ski lodge in Austria, twice – great fun and very good for my German (dialect). I learned about Slivovitz! and Gretchen, the innkeeper’s blonde, pig-tailed, sixteen-year-old daughter – because I spoke the best German, she chatted with me in the evenings when everyone else played cards. Our language teachers also encouraged us to buy French and German editions of the Bible to follow the lesson in Chapel – brilliant for our grammar and vocabulary.’ Robin Lake (Benson 1952-57)

‘I was lucky enough as a Modern Languages student, to have two top-notch teachers: Peter Willey for German and Mr Storrar for Spanish. They brought the languages alive and made them a joy to learn.’ Thomas Courtenay-Clack (Hardinge 1954-59)

‘Peter Willey was the first, but not the last, to comment on my Anglo-Saxon accent.’

Michael Llewellyn-Smith (Orange 1952-57)

Another of the post-war group was Douglas Young, described in this tribute in the Year Book when he finally retired:

‘Douglas joined the Common Room in 1946, after a long and debilitating spell as prisoner of war in the hands of the Germans. In his 31 years, he held the Lynedoch for eleven and the Benson for seven, and was Senior Assistant Master for his final three. He taught many subjects, but principally languages: French and, if required, Italian, but, it is clear, not German.’

Douglas Miller (Benson 1951-56) remembered him as ‘a strong disciplinarian and decent teacher,’ and Jeremy Watkins (Blücher 1951-55) wrote ‘I remember being admonished by “Black Douglas” as I think we called him: “Watkins, why is it when I hear you sing in Big School, I can hear your every word at the back of the Hall, and yet I cannot hear a word you say in my classroom?!”’ Richard Wellesley (Benson 1948-53) had a longer tale to tell:

‘It was my first year and I was in the Lower Third. Douglas Young was my form master. I was the youngest and the smallest in the class. DY was an excellent form master, and he took the trouble to make his lessons interesting and varied, as well as informative. He was a particularly good teacher of French, and we would often have to learn and recite French poetry. One day, we came across a popular traditional French song Sur le Pont d’Avignon. “Does anyone know the song?” he asked. Unwisely, I put up my hand. “Come up here and sing it for us,” he demanded. I sat on my hands. He repeated his demand. There was no way I was going to sing in my piping treble voice and make a fool of myself in front of the whole class, all of whom were bigger than me and many already had deep broken voices. There were a few moments of deathly hush. “Come and see me after the class,” he said, and I knew what that usually meant. After the class he gave me the surprisingly modest punishment of pumping up his bicycle tyres. I was still cross with him for embarrassing me, so I decided to get my revenge by pumping up his tyres until they were on the point of bursting. The next day he told me one of his tyres had burst on the way home. He was nice enough to laugh the whole matter off. I did not confess – although I think he may have suspected – that his burst tyre was exactly what I had intended.’

According to Bobby Baddeley (Picton 1948-52), ‘Ned Catterall was a charming new teacher whose hutted classroom in old Queens Court enticed nesting birds. This was too much for the boys, who rejoiced in making lessons chaos.’ Later, Catterall seems to have toughened up somewhat:

‘I managed to get through my time with only one beating and that was from Ned Catterall for possibly not doing much in the way of German homework. I do remember that it hurt quite a lot and it was certainly uncomfortable to sit down for a good few days. It clearly had no effect because I can’t speak a word of German now – and never could.’ John Alexander (Talbot 1954-58)

‘My favourite subject was my voluntary subject, German. This was taught firstly by “Schned” Catterall up in the old “Tin Tabs”, where we alternately froze in the winter and sweated in the summer, but his tutelage gave me an excellent basic grounding in the language, including the use of the old Gothic script. Later, Peter Hincks took on this task and I well remember his exhortation whenever one failed to meet his high standards: “Tough my child, take a reminder,” as he doled out extra work with a devilish grin on his face.’ Jerry Yeoman (Anglesey 1955-59)

The ‘Tin Tabs’ may have been the classrooms which featured in the following incident, recounted by two OWs, although neither of them named the teacher concerned:

‘The cabin classrooms had very basic lights: bulbs hanging from the ceiling with plain white plastic shades. One of our French lessons took place first period after lunch. I believe it was Wednesday when the staff lunch was always curry, and our teacher had a reputation of sometimes having one too many drinks with the curry to cool it down. On this particular occasion, before he came into class, we stood on our desk benches and held the lamps off to one side. At the given word we released them simultaneously so that they were all swinging nicely in unison. The teacher took one look and then vanished out of the room – that was a free lesson for us!’ Richard Craven (Hill 1950-54)

‘I was beaten by an usher, once, for swinging around the ceiling lamps in class to try to make the usher think he was drunk. (He did have a reputation for enjoying the odd glass at lunchtime).’ John Le Mare (Stanley 1950-55)

But perhaps the most unusual Modern Languages teacher at Wellington was not a teacher at all. Neil Munro (Talbot 1952-56) recalls that ‘Peter Willey became ill and I, in the Modern Language Sixth Form at the time, was deputed to teach Remove A in German. I have often wondered whether my parents received a fee discount that term.’